Archive

2021

KubaParis

Reading the Air

Location

GiG MunichDate

18.11 –20.01.2022Curator

Magdalena WisniowskaPhotography

Mathias R. ZausingerSubheadline

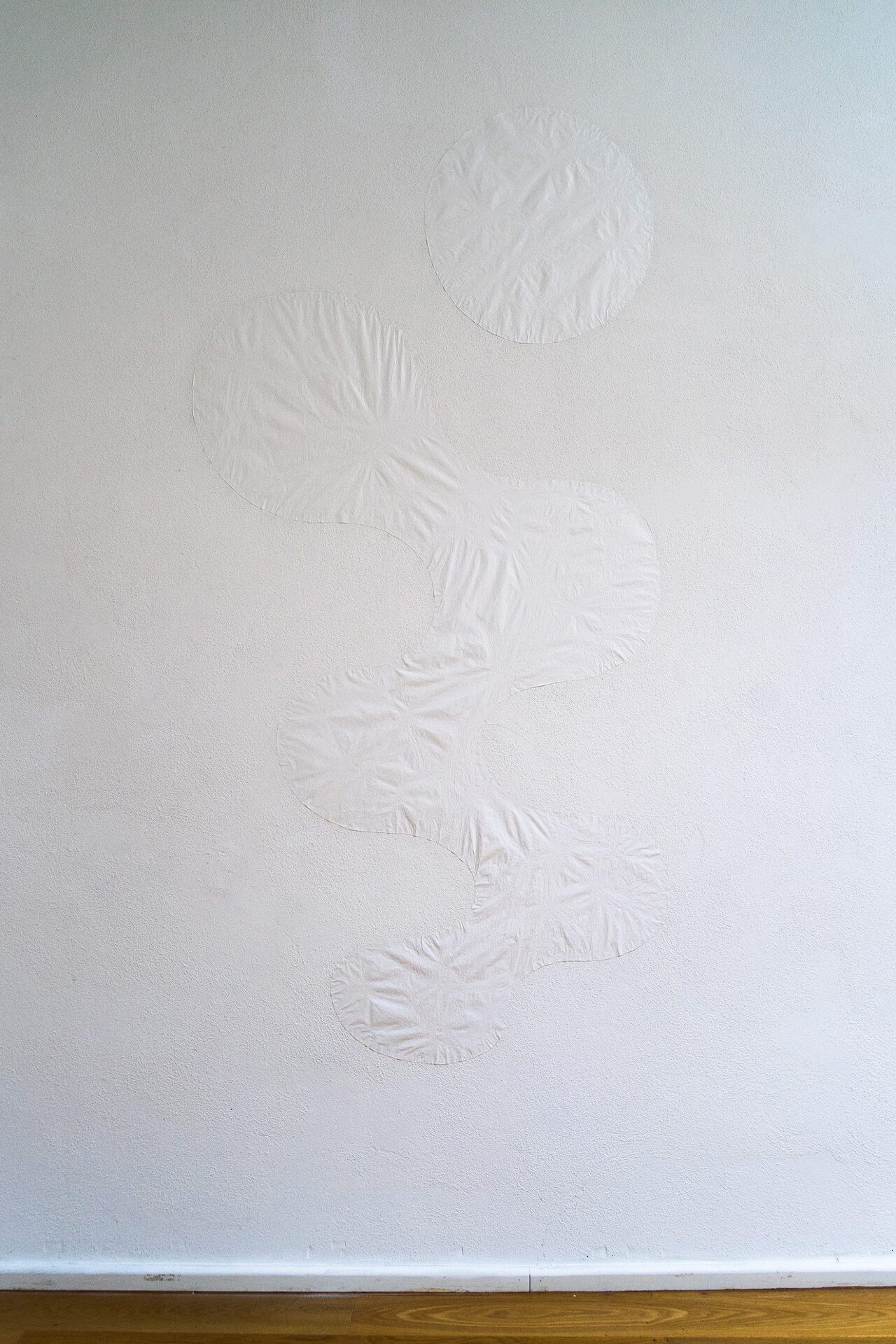

‘Reading the Air’ is GiG Munich final exhibition of 2021 with new work by Kalas Liebfried. The exhibition is part of the ‘Thinking Nature’ series hosted by GiG Munich and funded by the Department of Art and Culture, MunichText

When we first see Choromatsu, the monkey starring in Sony’s groundbreaking commercial, he is standing still, eyes closed, listening to music on his walkman. He seems at peace, lost in his hidden inner world. He breathes deeply and slowly. We then read in subtitles below, ‘The progress in sound continues, but what about mankind?’ For music can now be everywhere. Not limited to the concert hall or the family piano, the radio or the hifi, it is now outside, with us, in nature.

For Kalas Liebfried, this is the point at which music becomes truly impressionist, catching up with the history of art. Impressionism in painting was in part a consequence of artists, who with the help of the then newly developed tubes of paint, taking their easels outside and painting en plein air. Impressionism for him is thus less about a technique or style of painting and more about bringing the outside in, or rather the inside out.

This inside longing for the outside is what Adorno means when he writes after Kant,

Authentic artworks, which hold fast to the idea of reconciliation with nature by making themselves completely a second nature, have consistently felt the urge, as if in need of a breath of fresh air, to step outside of themselves. Since identity is not to be their last word , they have sought consolation in first nature: Thus the last act of Figaro is played out of doors (…)

Art can be a copy of nature, in that something, anything, can be painted or drawn from life. But in the Kantian aesthetics Adorno is working with, art is like nature, because the aesthetic experience of art is based on and is the same as the aesthetic experience of natural beauty. Already when we experience nature as beautiful, we experience it as something more than it is, an image if you will. The nature that we see and feel is both the same nature as always and yet different, because it is beautiful for us. For art to share in the beauty of nature it must also have this ‘more' and become in this way a ‘second nature’. Art that must be both itself and an excess, steps outside of itself, and this is why it seeks nature, even if, as Adorno mentions, it is only by staging Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro’s fourth act in the moonlit garden. In nature, art can take a breath. It breathes.

The advert for Sony’s walkman marks a moment in time in which the reconciliation between art and nature that Adorno had deemed impossible, seemed almost tangible: a rare moment of technological joy and optimism. Liebfried’s exhibition ‘Reading the Air’ is a reminder of the tangibility of this reconciliation. We see a hyperreal Choromatsu, listening with his headphones; we see his hands holding the walkman. And what we hear is the inside that always surrounds us - that we bring with us outside. This is the sound of our own breath, air rushing through the canal of our inner ear.

Magdalena Wisniowska