Archive

2021

KubaParis

Interiors

Location

Ashley BerlinDate

15.07 –07.08.2021Photography

Ben MarvinSubheadline

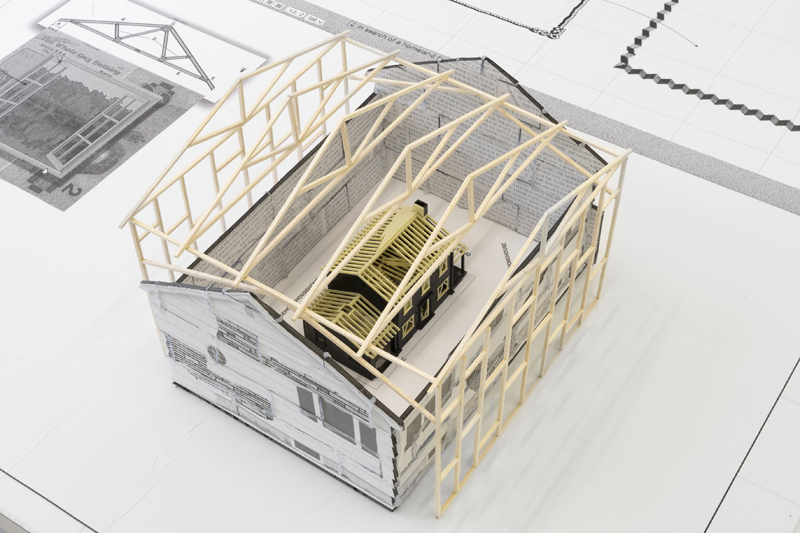

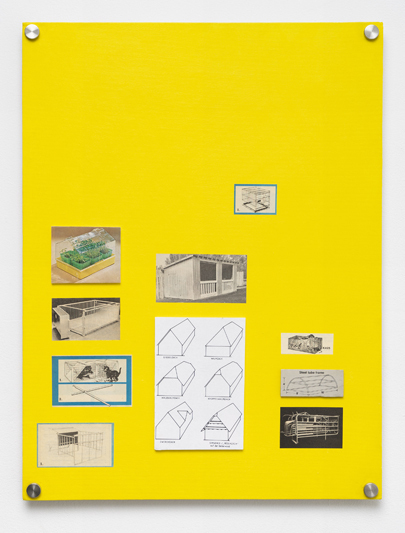

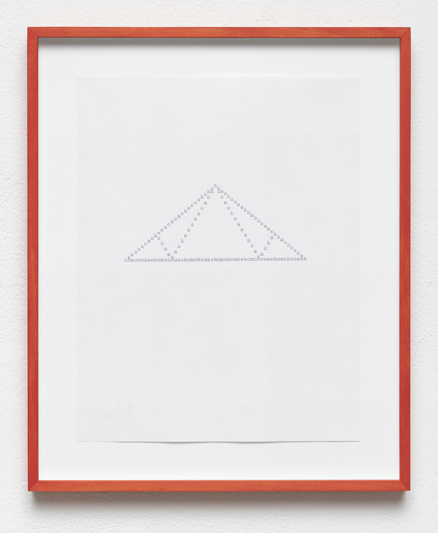

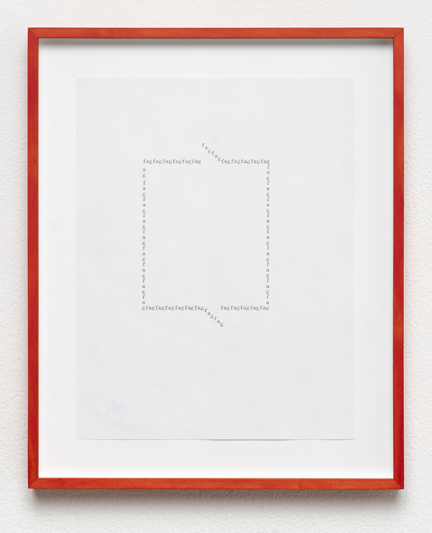

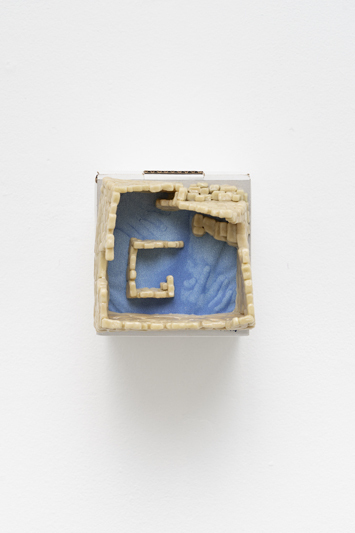

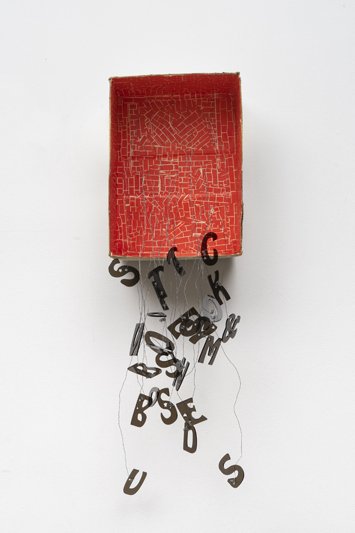

Interiors is a critical reflection on the architectural glyph of the home and its entanglement with notions of isolation, remoteness, and embodied queer politics. Saturated as a semantic referent for safety, sanctuary, and isolation, the concept of the home is made accessible through the vernacular of architectural modeling, drafting, and archive display—while at the same time upsetting this web of meaning through the aesthetic processing of remote living and rural industries. The double entendre folded inside ‘concrete poetry’ is made productive as a site to read the built space of architecture through the material inscription of language and vice versa. In his multimedia installation, artist Alex Turgeon places systems within systems, symbols within referents, structures within models, and visualises hidden architectures within the home, exposing the grammar of the unheimlich employed in the claim on neutrality of what is defined as inside and outside. Folding in on itself, the topological landscape is watched over by a screen performing as the sky. The blueprint structuring the archival display is replicated on a Berlin Litfaßsäule, a public advertising pillar, in close proximity to the exhibition space, performing the function of a remote access point or interface. Every inside has an outside has an inside and an outside, to which there is an inside and an outside... The exhibition will be accompanied by an artist talk on July 24th with author and art critic Kristian Vistrup Madsen. Alex Turgeon (Halifax, Nova Scotia) is an interdisciplinary artist primarily concerned with how the poetic space of architecture and the built space of language manage definitions of sexuality against the backdrop of gentrification. He received his MFA from Rutgers University in 2020 and BFA from Emily Carr University of Art + Design in 2010. His work has been presented across Canada at Franz Kaka and Art Metropole (Toronto) Or Gallery (Vancouver) and throughout Europe at the Tate (Liverpool), KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin), Tunnel Tunnel (Lausanne), San Serriffe (Amsterdam) Contemporary Art Centre (Vilnius) and as part of ‘Poetry as Practice’ an online exhibition hosted by Rhizome and the New Museum (New York). In 2017 his first collection of poetry titled Love Poems for Ceres was published by Broken Dimanche Press, Berlin.Text

WHAT IS HOME, AND HAVE YOU EVER TRIED TO DRAW A HOUSE IN ONE CONTINUOUS MOVEMENT?

In Germany there’s a well-known puzzle for children. The rules are simple: A house is drawn in one line without lifting the pencil and without repeating the same line. While drawing, each line segment of the house is accompanied by one syllable of the vocal incantation “Das ist das Haus des Ni-ko-laus” (This is the house of Santa Claus). For little girls there’s a particularly charming version, “Wer dies nicht kann, kriegt keinen Mann” (Who isn’t able to do this, won’t find a husband).

Mathematically speaking, this puzzle is a problem in graph theory, a Eulerian trail, in which each edge of the graph

is visited once. According to mathematics, every solution to the puzzle starts off at node 1 and ends at node 2 or vice versa. There are 44 paths to solve the puzzle and 44 more if you count each path in reverse from node 2 to node 1. Also according to mathematics, there are only 10 ways to fail the puzzle.

To fail something is to be unsuccessful in accomplishing a purpose. So by definition, you could also fail the game by never playing. For instance, because you disagree with how technical skill is abused as the backdrop to a heteronormative fiction or because you are deeply suspicious of the evolution from system of belief to system of capital and why should you draw the house of someone you’re suspicious of?

So here are five alternative nodes which will help you fail the game (choose your own 1 of 88 adventures):

1 — A home is a structure within a structure, that is a status in a system or a feeling within a place, that is the difference between a house and a building. If one were to try and formalize this in an equation, one would probably start with architecture + subjectivity = home, maybe even as a product of multiplication rather than just a sum. The subject here is the crucial variable, because it is the subject who feels the sharp edge between feeling or not feeling at home cutting its flesh.

2 — Etymologically, “house” is closely related to “hide”, which implies a binary tension between inside and outside, sanctuary and threat. Therefore it is rather fitting that the German language associates the eerie and uncanny with the unhomely. Yet sometimes the inside, even if it is a sanctuary for queerness, can be found equally as unheimlich, because its safety is conditioned on the exterior façade of normative citizenship.

3 — Repeat a word several times and it loses its meaning. This phenomenon is also known as semantic satiation. So you could be repeating HOME HOUSE HOME HOUSE HOME HOUSE or HOMO HOUSE HOMO HOUSE HOMO HOUSE and the result would be nearly indistinguishable.

4 — The household was called oikos in Ancient Greece and was ruled by the male patriarch, who presided over the economic affairs within his four walls distinct from but still inside the polis. This is the historical materiality from which we derive the concept of economy. Today, this story takes on a different dimension in that the resource which has truly become scarce is land and with it housing, and that a scarce resource in disaster capitalism stands erect on the legal version of Viagra, that is usury over useful distribution.

5 — In Interiors, Alex Turgeon traces the structure of the feeling of home. A table becomes a landscape with windows to the interior, and a screen looming over the table performs as the sky.

The sky says,

Though sticks and stones may house my bones Words will always stack together

To make the four walls of which they frame And call me poetry by name.

In other words, if you read architecture as poetry (as that which creates what didn’t exist before), then you will also find the only way to enact the future impossible is by mobilising a present imperfect. Or: to dismantle the house of Saint Nicholas, you have to break the line.

Steph Holl-Trieu