Anna McCarthy

Washing Cycle

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

Advertisement

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

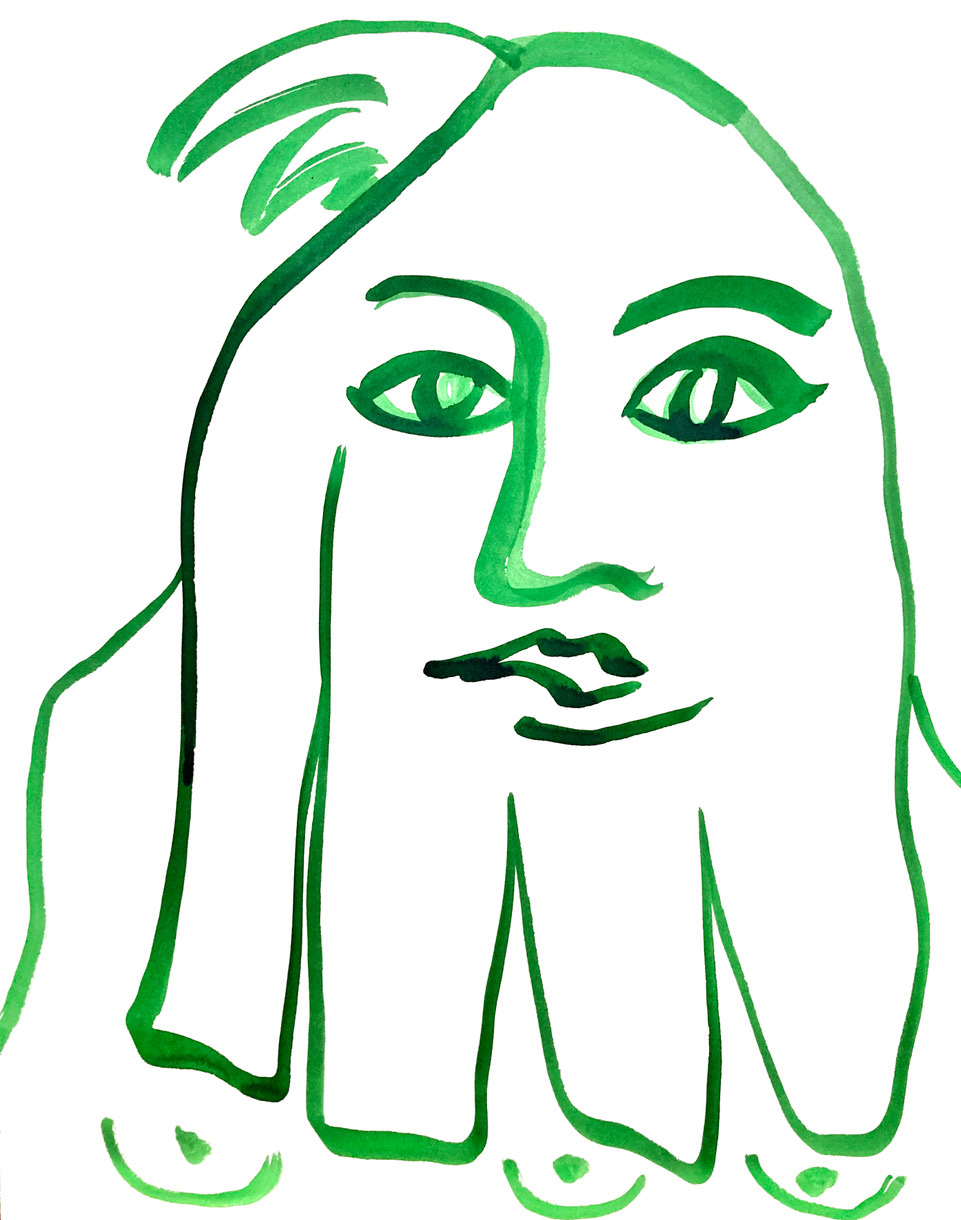

Anamash, 2022, ink on paper, 35.56 x 27.94 cm

Evergreens Cemetery (Overgrown), 2022, acrylic, ink, permanent marker, Old Man’s Beard, stainless steel, brass, pencil on canvas and vinyl, 250 x 136cm

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

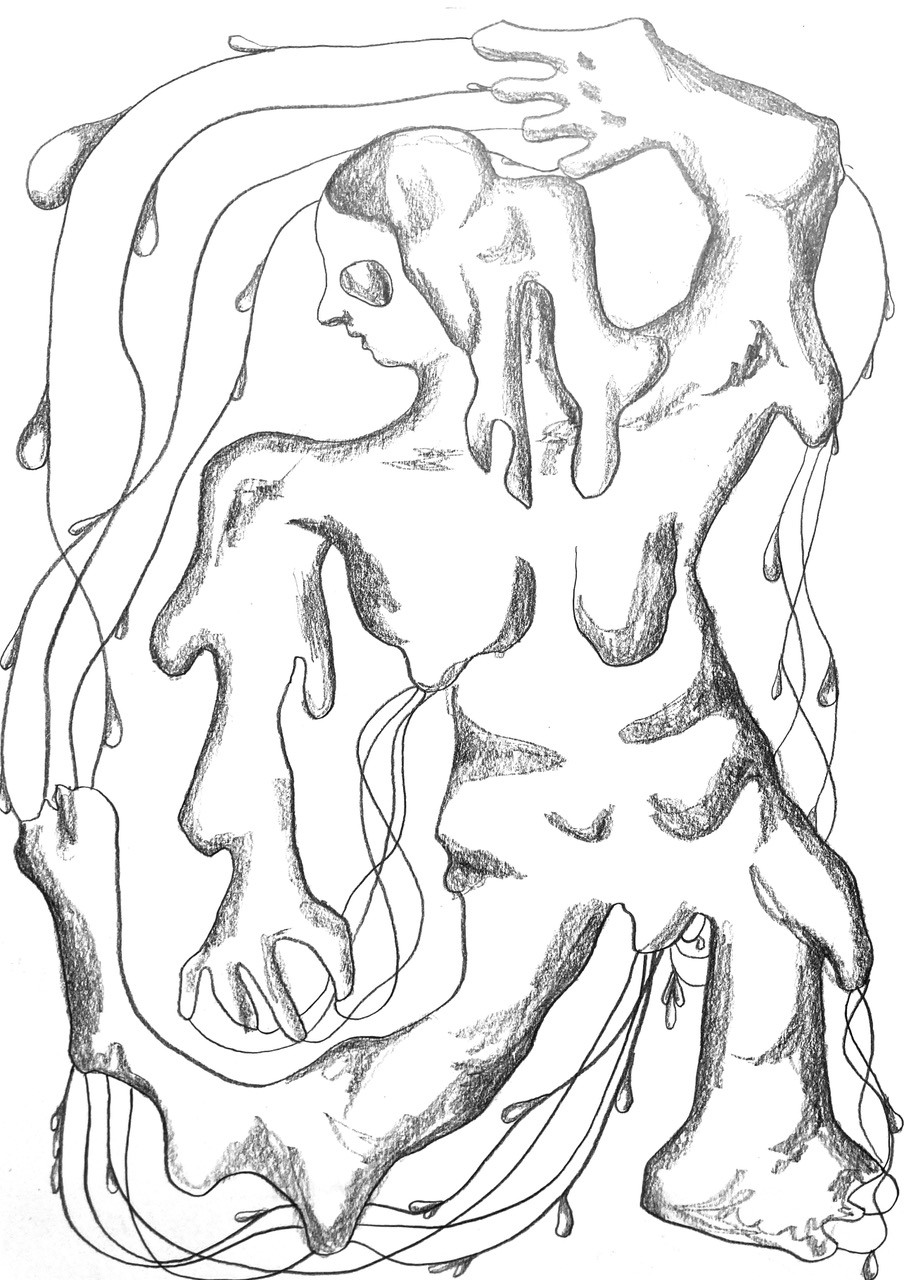

Aspik (Frau), 2022, pencil on paper, 29.7 x 21cm

Shackles / Kitchen, 2022, stainless steel, chrome, leather, coins, glue, bolts, wire, keys, 145 x 44.5 x 26.5cm

Shackles / Kitchen, 2022, stainless steel, chrome, leather, coins, glue, bolts, wire, keys, 145 x 44.5 x 26.5cm

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

Evergreens Cemetery (Quilt), 2022, acrylic, permanent marker, pencil on canvas and vinyl, 220 x 137cm

Cemetery Rose, 2022, glass, water, rose, acrylic, 17 x 15 x 15cm

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

Washing Cycle (tryptych), 2022, permanent marker, pencil, acrylic on wood, 3, each 21 x 15.4 x 2cm

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

Window Eye II, 2022 pencil on paper 35.56 x 27.94cm/ f*ck the patria... (cutlery 4 the people), 2022, stainless steel, leather, nails, engraving, 35 x 20 x 5cm / Holes...Brain, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 x 2cm

The Crying Series (Peaches), 2022, watercolour on paper, 35.56 x 27.94cm

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

Anna McCarthy, Washing Cycle, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Sperling, Munich

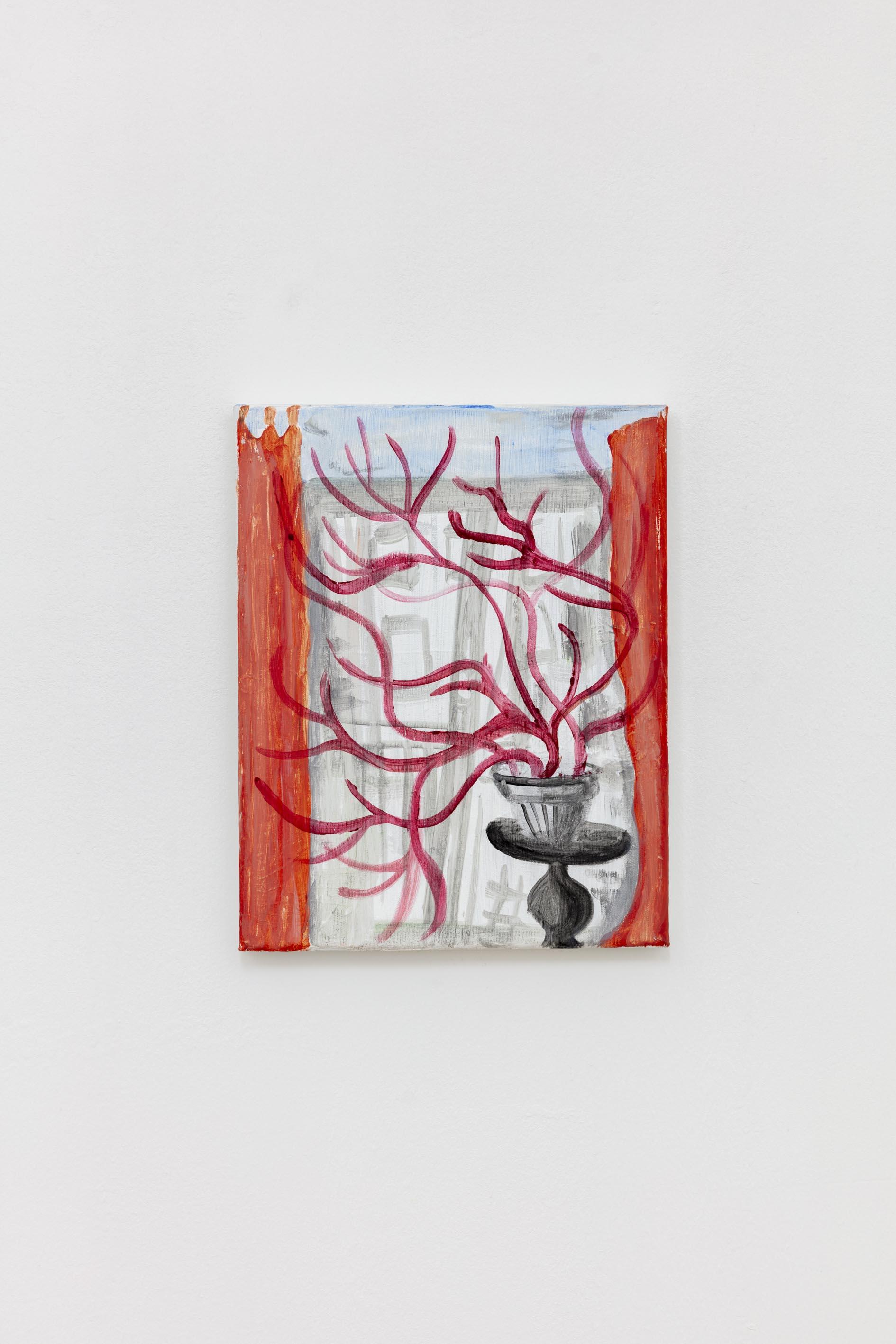

Westend Plant, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 24cm

The washing cycle designates a washing machine program and, along with it, a detail taken from the reality of housework (also unpaid or reproductive labor). After washing, laundry returns from the machine fresh, soaked in water and is hung up to dry, only to then be worn and made dirty again. Housework does not produce anything and never ends. It is with good reason that it has been likened to the agony of Sisyphus (Beauvoir, 1949).

Indicators of domestic labor, as well as water, appear in several of Anna McCarthy’s works: In the triptych "Washing Cycle", a piece of clothing lies on the floor, is washed, then dried – repeat. A hand-engraved stainless-steel sink protrudes from the wall. A pencil drawing shows clothes on a clothes rack. The moisture from the laundry has created a microclimate in which clothes, drying rack, and the rest of the cramped living space thrive into a pacified and/or claustrophobic whole.

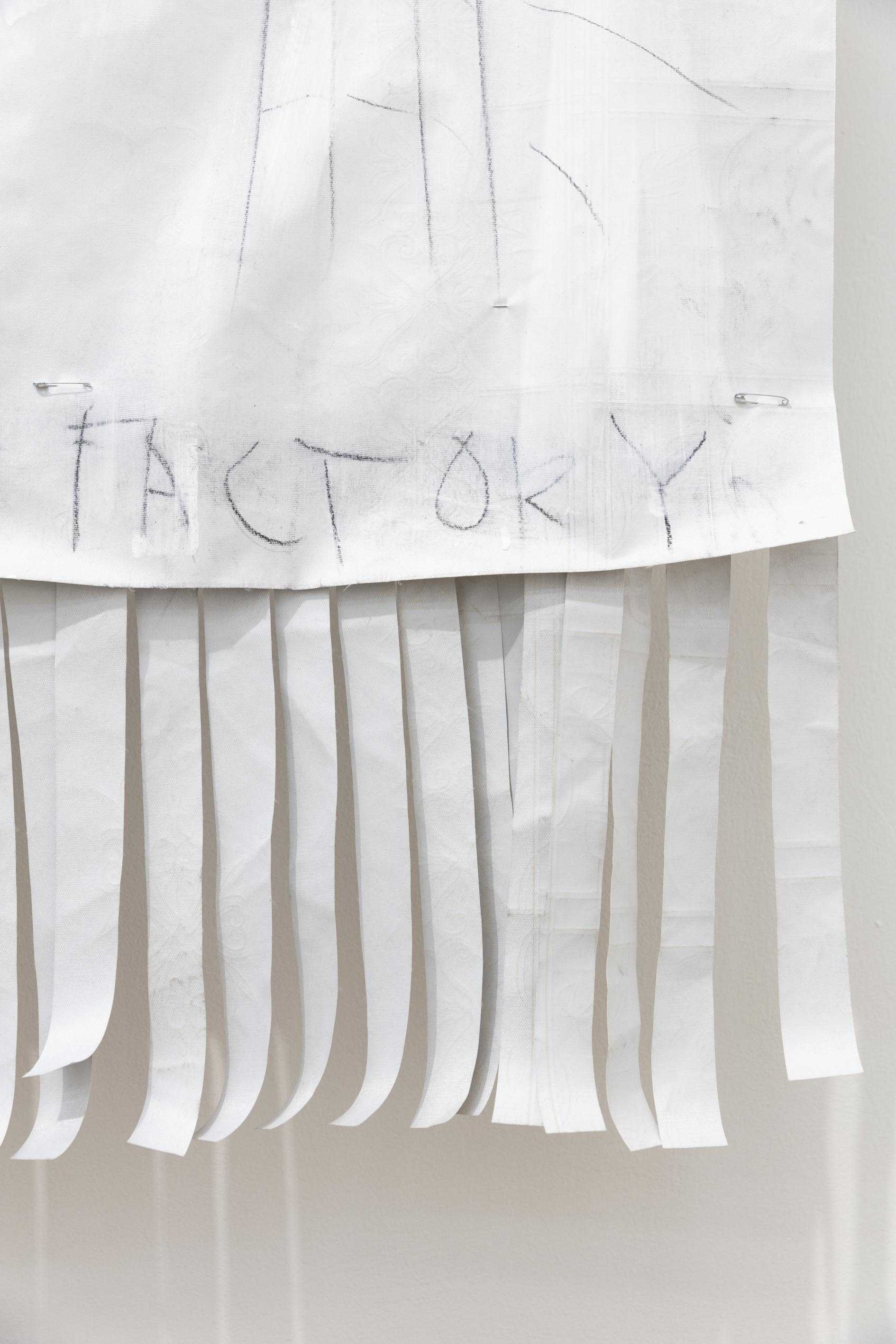

Things are less holistic in two large-scale drawings on reverse-printed and pressed plastic, showing a rough mapping of the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, through whose quiet greenery a dead-straight and much-traveled axis was traced in 1933 with the construction of the Interboro Parkway (now Jackie Robinson Parkway). In the large-scale drawing "Triangle Shirtwaist Factory", McCarthy references one of the deadliest industrial disasters in U.S. history: In 1911, 123 women and girls – mainly Jewish and Italian migrant workers – and 23 men died during a fire at the Manhattan-based garment factory. Six victims, unidentified at the time, were buried in the Evergreens Cemetery. The death toll was so devastating because, following a common practice at the time, factory owners had locked exits to keep workers from taking breaks or stealing materials. The disaster galvanized important labor rights movements and strengthened the International Ladies’ Garments Workers’ Union, one of the most radical and predominantly female unions in the United States. The interdependence of paid and unpaid, public and private labor is also expressed in McCarthy’s drawing process in these works: Black felt-tip pen saturates the plastic material, seeps through the acrylic paint and pencil. The pattern embossed in the plastic only becomes visible on its reverse side through McCarthy’s application of paint. To put it succinctly, one could say that the artist thus reveals the parts of invisible work in the visible.

Crying is, at least physiologically, also a process of washing. To this day, it is commonly interpreted as an expression of weakness and therefore, in patriarchal logic, attributed mainly to women*. Crying as a means of controlling aggression is a less common interpretation. In Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland”, the protagonist, who grows into a giant after biting into the enchanted cake, cries a perilous sea of tears that threatens to sweep away everything around her. Shortly after and dramatically shrunk, she almost drowns in it herself. For Alice, the moment of shrinking is coupled with an identity crisis and the uneasy question of what distinguishes her from her friends. The frightening wave of tears can easily be read as anger at the transition into sexualized adulthood, which, especially for young women*, comes with various degrading procedures of comparability (the everyday path through public space may serve as an example). In McCarthy’s black watercolor drawing, we see a woman crying. The woman’s wide eyes, full mouth, and the film noir aesthetic lend the scene a subdued sexual undertone; the tight cropping and extreme close-up makes the viewer feel intrusive. The woman’s mood or the reason why she is crying, however, remains unclear.

Exuberant forms are found in several works: Viscous liquid oozes through boxy windows into an empty interior, clothes spiral out of the many compartments of an open closet, plants sprawl and intertwine. In McCarthy’s work, the interior appears as a closed system that offers solace but can also imprison or obscure. In keeping with the artist’s slogan of “giving chaos to structure”, a precarious yet balanced stability seems to have been achieved in the painting "My Wardrobe".

We encounter another form of equilibrium in the pencil drawing "Aspik (Frau)". The title is a synonym for jelly – a term that captures the homogenization of all human labor in the commodity form (Marx, 1867). The body of the figure takes up the page almost entirely. It is in motion and flux, but not in disintegration. The lines emanating from the figure’s fingers and feet form a self-contained circuit along whose graceful and interwoven lines the woman steadily reconstitutes herself, drop by drop.

Stephanie Weber