Annabelle Agbo Godeau

Suspense

Project Info

- 💙 Orangerie Munich

- 💚 Tinatin Ghughunishvili-Brück , Co-curator: Jorge Esda

- 🖤 Annabelle Agbo Godeau

- 💜 Tinatin Ghughunishvili-Brück and Jorge Esda

- 💛 Marc-Pascal Berger

Share on

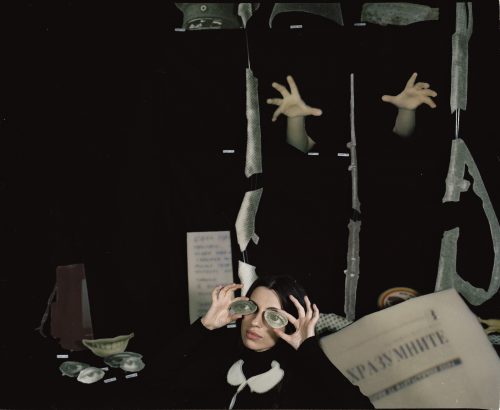

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Advertisement

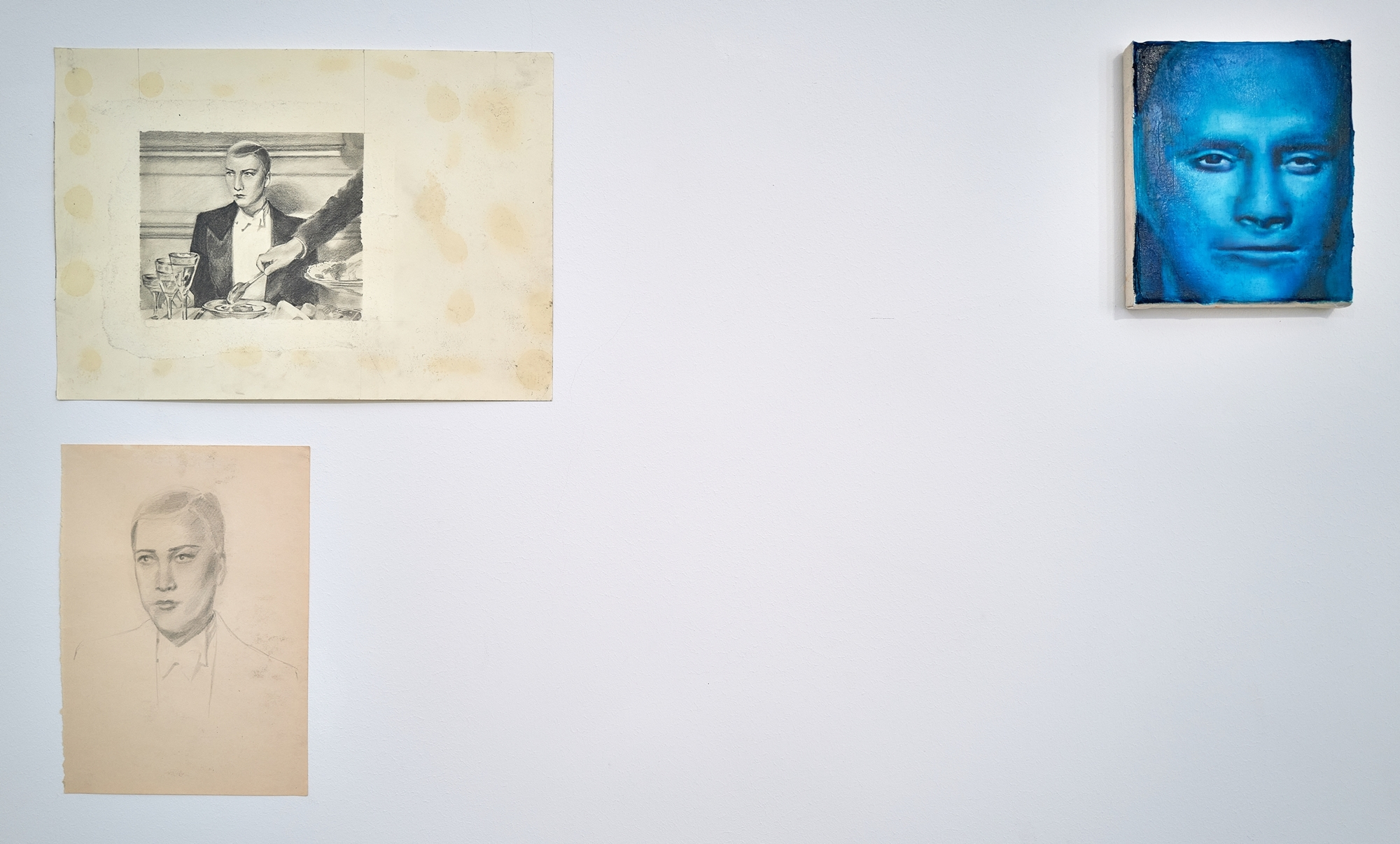

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Suspense, Exhibition View, Orangerie Munich, 2022

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Evangelion, Oil on canvas, 150x130cm, 2022. All rights reserved ©

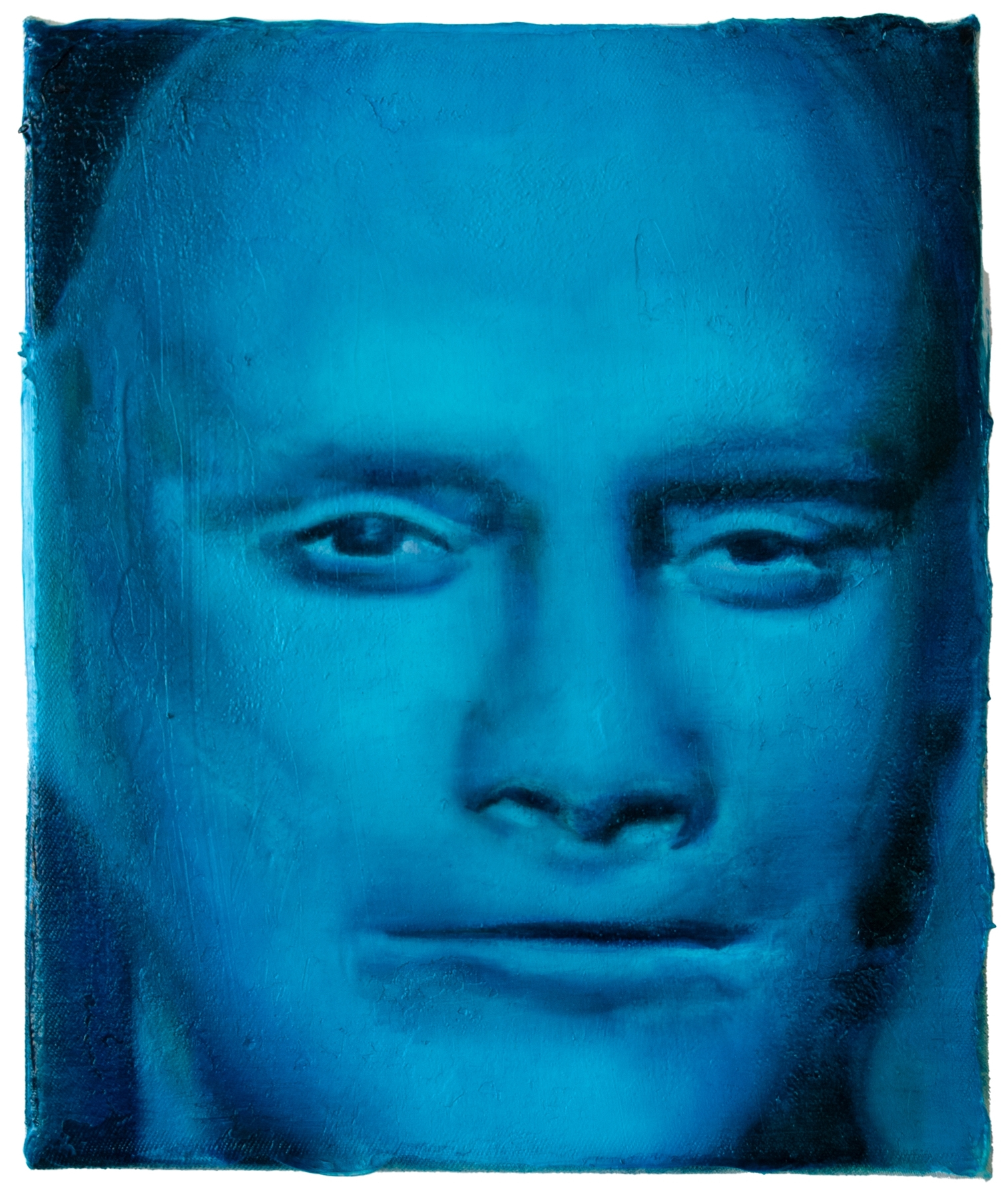

Annabelle Agbo Godeau, Fantomas, Oil on canvas, 18x22cm, 2022. All rights reserved ©

A solo show featuring the works of artist Annabelle Agbo Godeau was shown in the Orangerie of Munich from 27 July to 31 July 2022.

Gathered in private spaces, the protagonists of Annabelle Agbo Godeau's paintings do not seem to be fully comfortable. They never return the glances of their surroundings and seldom look at the viewer outside the picture, even though someone is always looking at them. This unusual choreography of the gaze runs through the artist's current work like a common thread. Perhaps it refers to the perpetual dis-communication between people, perhaps to the refusal to be constantly observed in times of voluntary and involuntary self-expression, or to our inability to perceive without prejudice. There could be countless other reasons. The viewer never gets to see all the elements involved, and so „Suspense“ invites the visitors to stroll through a complex work that raises questions whose answers are not found in the images on display.

The private spaces depicted in the works seem to become a stage on which the characters suddenly become public. It is in this domestic architecture that an atmosphere of „Suspense“ is created while shelter fades away. Is this tension generated by the mere presence of realities that have been hidden and denied by the one-sided Western culture, or is something else going on? Do we, like in a video game, have the key to change the future of the characters by starting to perceive them instead of just looking at them?

The title of the exhibition „Suspense“ comes from a term connected to film and literature that describes a special narrative technique used to build up tension. Thus, to create „Suspense“, elements have to be shown that the viewers are interested to know more about. Or in other words,- the viewers get some information from which questions arise.

Annabelle Agbo Godeau uses the motifs of film and photography, which are anchored in our visual memory with their narrative structures and patterns, or the historical or present image references, which usually correspond to certain social expectations. She replaces them with different and more diverse content and protagonists.

Referring, among other things, to the theories of the German cultural scientists Aleida and Jan Assmann, cultural memory is examined in the context of this exhibition as "the tradition within us, the texts, images, and rites that have solidified over generations, over centuries, sometimes even millennia of repetition, and that shape our consciousness of time and history, our view of ourselves and the world“ (1).

By allowing both remembering and forgetting, Annabelle Agbo Godeau's work makes an important contribution to overcoming the constructs of identity, representation and visibility. Through the representation of women in the history of medicine and science, a tribute to Black Joan of Arc and Orpheus in contrast with a series of Fantomas, a new and transformed visual language is created which supports a debate and questions collective processes of observing, remembering and repressing. A re-staging and artistic re-writing of collective/cultural memory sets as its goal the avoidance of repeating the mistakes of human history. The artist does not illustrate and comment on this past, but presents alternative scenarios, reinvents the past, as it were.

If the limits of language are the limits of the world, as Wittgenstein expresses it in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (2) , then the texts that subtitle the paintings expand the possibilities of their figures and the actions they contain. „Now we see, and nothing changes“ or „We used to say that if we had seen it, it would have made a difference." Can be read on some of the paintings.

By reflecting on the „invisible," the texts explore how perspective fundamentally changes the way contemporary narratives are constructed and their impact on a group's identity and self-assessment. But they also alert us to the fact that we may not be able to change our perceptual habits.

(1) Assmann, Jan (2006): Thomas Mann und Ägypten. Mythos und Monotheismus in den Josephsromanen. Beck: Munich.

(2) The sentence “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world” first appears in Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1921). Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung. Suhrkamp Verlag (1 January 1963): Frankfurt

Tinatin Ghughunishvili-Brück and Jorge Esda