Groupshow

make room in your mouth

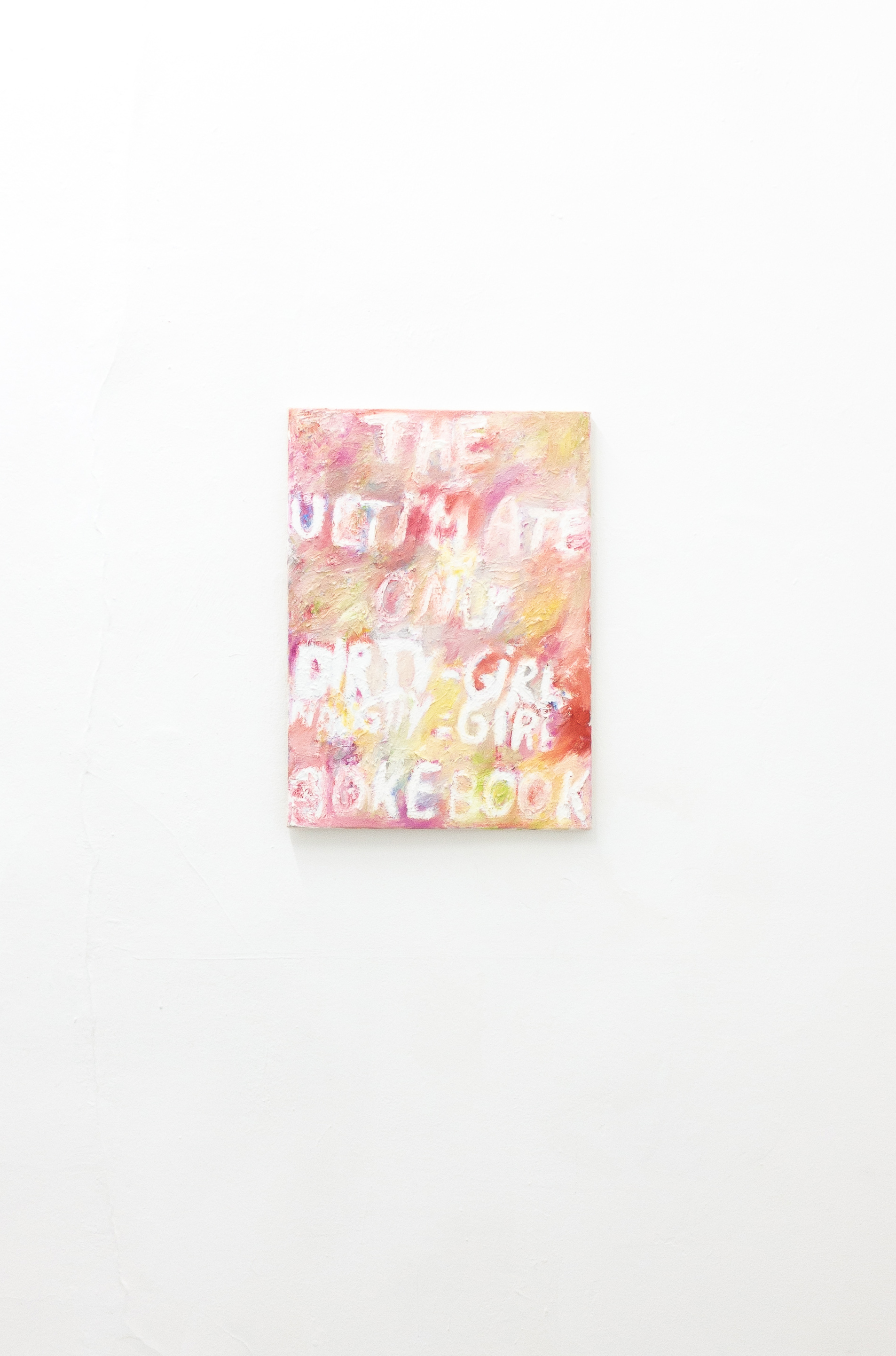

Gritli Faulhaber, Jokebook, 2021, Oil on canvas, 65 x 47 cm

Advertisement

Exibition View, Gritli Faulhaber, Julija Zaharijevic, WAF

Julija Zaharijević, Eurotrash, 2022, 12’46 audio loop, speakers

Exibition View, Gritli Faulhaber, Julija Zaharijevic, WAF

Exibition View "make room in your mouth" curated by Olamiju Fajemisin, WAF

Shaun Motsi, Untitled (en Brunaille), 2021, Oil on wood, 25 x 30 cm

Exibition View "make room in your mouth" curated by Olamiju Fajemisin, WAF

Adji Dieye, Circuit Fermé, 2017 3’03 video loop, projector

Shaun Motsi, Untitled (en Brunaille), 2019, Oil on primed aluminium panel, 30 x 40 cm

Shaun Motsi, Untitled (en Brunaille), 2019, Oil on primed aluminium panel, 30 x 40 cm

Nicolas Cilins, Talk to me!, 2021– , Digital performance, on-demand workers, HD monitor on stand, conference hardware and software

Nicolas Cilins, Talk to me!, 2021– , Digital performance, on-demand workers, HD monitor on stand, conference hardware and software

Exibition View "make room in your mouth" curated by Olamiju Fajemisin, WAF

make room in your mouth

"we wanted to lean over this phrase like a charted city, to make a point, create a mouthspace, myth of hear or say: hier; in this net of tongues, one path was well-sprung, a mistake, mystique. lingua franca stuck on your foreheads, almost touching and already legends: you are here, ich bin wer, a game of routes, but whatever we said the words did not arrive."1

In the same way that psychoanalysis makes use of dream interpretation, it also benefits from the study of symptomatic actions, the numerous little slips and mistakes in speech and language that we make. Sigmund Freud pointed out that these phenomena are not accidental, that they have a meaning and can be interpreted, and that it is justified to infer from them the presence of repressed impulses and forbidden wishes. Language is slippery in the same way that recalling a dream is.

A Freudian slip, or parapraxis, can be caused by an internal contradiction against one’s own utterance, sometimes a contrasting substitution for the one intended. In this case, the wording of an assertion removes the purpose of the same, and the error in speech lays bare the inner dishonesty. Here the lapsus linguæ becomes a mimicking form of expression, often for the expression of what one does not wish to say. It is, thus a means of self-betrayal. A pharmacist writing a prescription for a woman crushed by the financial burden of the treatment was interested to hear her suddenly say, “Please do not give me big bills because I cannot swallow them.” Of course, she meant to say pills.

Parapraxis not only occurs as slips of the tongue, it might also take the form of misreadings, mishearings, and mistypings. An example of the letter can be found in the so-called “Sinner’s Bible”, in which the word “not” was omitted from the seventh commandment, causing the verse to read “Thou shalt commit adultery”. It is said that the printer had to pay a fine of two thousand pounds for the omission. Another biblical misprint dates back to 1580 and concerns the passage in the Book of Genesis where God tells Eve that Adam shall be her master and shall rule over her. In the German translation the word Herr (master) was substituted with Narr (fool): “Und er soll dein Narr sein.” Rumour has it that the error was a conscious machination of the printer’s wife, who refused to be ruled by her husband.

Some things can only be articulated through linguistic deformation. Ilse Aichinger’s prose poem “Bad Words”, for example, expresses distrust of the restrictive notion of “better” words, preferring to pounce on the second and third best, from which the good always hides ever so slyly, if only from the fourth best. “I now no longer use the better words ... I just had another expression on the tip of my tongue – not only was it better, it was also more precise, but I forgot it while the rain was pounding against the windows or while the rain was doing what I was about to forget.”2 Aichinger’s desire to leave behind false promises about the coherence of the world and its better words lead to a language of “bad words”, words that have been stripped of their misleading certainties, opinions, and ideologies. A language that is alienated by its will to be radically inadequate – only to reclaim it for the purposes of poetry.

“Make room in your mouth” is a line adapted from Layli Long Soldier’s poetry collection Whereas that confronts the United States’ “official” apology to Native American people from 2009. The book opens with the lines “Now / Make room in the mouth / For grassesgrassesgrasses”. One later learns that the image of grass refers to Dakota 38, the largest “legal” mass execution in U.S. history in which thirty-eight Dakota men were executed by hanging under orders from President Abraham Lincoln. “One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass. / There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect. / When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick. / When Myrick’s body was found, / his mouth was stuffed with grass. / I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem. / There’s irony in their poem. / There was no text.”3

This poetic treatise on the appropriation and subversion of language as it pertains to US violence and bureaucracy brings to mind M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008), an archive, a legal text, an impossible poem that draws solely from an eighteenth-century legal report on the violent death of 150 enslaved people. Lawyer and poet M. NourbeSe Philip takes the linguistic material of this document – a murder report – as the starting point for her book; the material is splintered, repeated, permuted, language is broken open until voices speak in tongues, “create semantic mayhem”.4 Zong!, as Philip writes, is an attempt “to not tell the story that must be told.”

1 Uljana Wolf: “Can you show me on se mappe”, translated from German by Sophie Seita

2 Ilse Aichinger: Bad Words

3 Layli Long Soldier: Whereas

4 M. NourbeSe Philip: Zong!

Sophia Rohwetter