Martin Chramosta

Miraggio. Martin Chramosta at Künstlerhaus Bregenz

Project Info

- 💙 Künstlerhaus Bregenz / Palais Thurn und Taxis

- 🖤 Martin Chramosta

- 💜 Lukas Maria Kaufmann

- 💛 Florian Raidt

Share on

Garden View

Advertisement

Lemon Ornament, GIF, 2020

Sperlonga, Iron, Ceramic, 2022

Exhibition View first floor

Ghost Town, Plaster, 2022

Exhibition View Gartensaal

Casa Ispirata XII, Ceramic, 2022

Casa Ispirata II, Ceramic, 2022

Casa Ispirata III, Ceramic, 20222

Exhibition View Gartensaal

Proben, Concrete, Bricks, 2022

Exhibition View Balkonsaaal

Caccia, Iron, Ceramic, 2022

Nightswing, Iron, Ceramic, 2021

FUR, Iron, Ceramic, 2022

Winterhafen, Iron, 2021

Exhibition View Balkonsaal

Exhibition View Dachgeschoss

Heft, Iron, 2022

Dear Diary, Iron, 2021-222

DE

Medaillons und Medaillen

zu Martin Chramostas Ausstellung „Miraggio“ im Palais Thurn und Taxis Bregenz

Das Medaillon wird gemeinhin als rund oder oval gefasstes Schmuckstück verstanden, als Talisman und Amulett. Es ist Träger von Emblemen, Inschriften, Initialen und Wappen sowie Abbildern geliebter Personen und mythischer Darstellungen. Um den Hals gehängt oder an Kleidung geheftet, trägt sein*e Besitzer*in es an und bei sich.

Als Stilelement taucht das Medaillon auch in der Architektur, in Raumgestaltungen und im Kunstgewerbe auf. Als Schmuckfeld oder Applike an Fassaden kommt dem Medaillon eine repräsentative Funktion zu. Es fungiert als Vermittler und Kommunikator zwischen dem Innen und dem Außen und erlaubt eine von der Flächigkeit der Fassade emanzipierte Zuschreibung, die auf den Inhalt, die Benützung oder die Besitzverhältnisse des Gebäudes sowie den Status seiner Bewohner*innen verweist. Der Medaille, der Numismatik zugehörig, ist ihre repräsentative Bedeutung eingeschrieben. Das von seiner Funktion als Zahlungsmittel befreite Metallstück mit Münzcharakter wird allgemein als Ehren- und Verdienstauszeichnung den jeweiligen Würdenträger*innen verliehen. Medaille und Medaillon sind über eine enge etymologische wie morphologische Verwandtschaft sowie Ähnlichkeit in Dimension und Materialität verbunden, und dennoch lässt sich anhand ihrer Unterscheidung das Verhältnis von Öffentlichem und Privatem, Repräsentativem und Persönlichem festhalten.

Die Werkgruppen Martin Chramostas geben Anlass, ebendiese Verhältnismäßigkeit neu zu betrachten. Die Motive einer Vielzahl von Kleinplastiken, die entweder direkt an der Wand angebracht oder in Überstrukturen mit suggestiver Modularität gefasst sind, beziehen sich beispielsweise auf visuelle Impulse antiker Monumentalbauten und mythologischer Schauplätze, aber auch auf Fundstücke des Alltags und Überbleibsel aus der künstlerischen Praxis. Diese Impulse finden in der vermeintlichen Trivialität ihrer Darstellung zusammen, indem sie zu Kompositionen werden, die in ihrer Direktheit mitunter an die dekorative Flamboyanz der 50er Jahre erinnern. In der Darstellungsform Chramostas liegt eine Hebelwirkung, welche die Frage nach der gegenseitigen Wechselwirkung zwischen Abstraktion als (stilistischem) Phänomen und Ästhetiken dekorativen Kunsthandwerks aufwirft. Die dadurch entstandene undogmatische Unmittelbarkeit der Werke ermöglicht Betrachter*innen, sich den in ihnen angelegten narrativen Strängen und persönlichen Referenzen zu nähern. So können die in dieser Ausstellung versammelten Werke in ihrem Zusammenspiel auch als Tagebuch oder persönlicher Reisebericht eines Aufenthalts in Rom gelesen werden. Die Synergie von „Öffentlichem“ und „Privaten“ ist nicht zuletzt auch im künstlerischen Arbeiten selbst und der Position von Künstler*innen in der Gesellschaft veranlagt.

Die meist roh belassenen Materialien wie Ton und Stahl sind in Fertigungsweisen verarbeitet, die zum Teil an die Techniken zur Herstellung von Schmuckstücken erinnern, wie zum Beispiel das Fassen von Edelsteinen in Gold oder Silber. Anhand der Fertigung wird auch der Status der Werke im Ausstellungsraum und ihrer Umwelt verhandelt. So tragen viele der Werke Chramostas zu gleichen Teilen die Attribute von Versatzstücken des Alltags und des urbanen Raums (z.B. Zäune und Tore) sowie auch Charakterzüge dezidiert klassischer Kunstformen. Es scheint, als würden die meist handwerklichen Fertigungsweisen die Pole zwischen Gegenstand und Objekt austarieren, indem sie Zitate zu Nachahmungen und umgekehrt Nachahmungen zu Zitaten werden lassen. Dekor als gestalterisches Element nimmt auch hier eine Vermittlerrolle ein.

Bei den zylindrischen Probebohrungen, die sich auf den Böden der beiden gespiegelten Räume des Obergeschosses ausbreiten, wurde die Fertigung ausgelagert und ist quasi vorangestellt. Als Fundstücke des öffentlichen Raums knüpfen sie gewissermaßen an den Titel der Ausstellung an. „Miraggio“ bezeichnet im Italienischen ein Trugbild. Der Künstler verweist damit auf Scheinlandschaften und -Architekturen, wie sie beispielsweise in Lustgärten des 18. Jahrhunderts angelegt wurden, aber auch in den verwaisten Zooanlagen Roms vorzufinden sind, wie sie in dem titelgebenden Video „Miraggio“ gezeigt werden. In diesem Zusammenhang können die Probebohrungen also als Befragung der Materialitäten des öffentlichen Raums, aber noch viel mehr als Befragung von Realitäten verstanden werden. - Lukas Maria Kaufmann

EN

Medals and medallions

on Martin Chramosta's exhibition "Miraggio" in the Palais Thurn und Taxis Bregenz.

The medallion is commonly understood as a piece of jewelry set in a round or oval shape, as a talisman and amulet. It carries emblems, inscriptions, initials and coats of arms as well as images of beloved persons and mythical representations. Hung around the neck or pinned to clothing, its owner wears it on and with him/her/them.

As a stylistic element, the medallion also appears in architecture, interior design and decorative arts. As a decorative field or applique on facades, the medallion has a representative function. It functions as a mediator and communicator between the inside and the outside and allows an attribution emancipated from the flatness of the facade, which refers to the content, the use or the ownership of the building as well as the status of its inhabitants. The medal, belonging to numismatics, is inscribed with its representative meaning. The metal piece with the character of a coin, freed from its function as a means of payment, is generally awarded as a distinction of honor and merit to the respective dignitaries. Medal and medallion are connected by a close etymological and morphological relationship as well as similarity in dimension and materiality, and yet the relationship between the public and the private, the representative and the personal can be determined on the basis of their distinction.

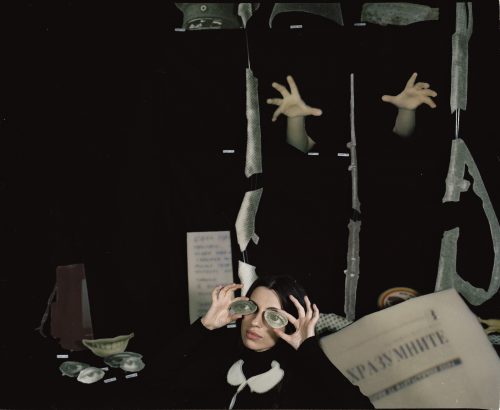

Martin Chramosta's groups of works provide an occasion to take a new look at this very proportionality. The motifs of a large number of small sculptures, which are either mounted directly on the wall or set in superstructures with suggestive modularity, refer, for example, to visual impulses of ancient monumental buildings and mythological settings, but also to found objects of everyday life and remnants of artistic practice. These impulses come together in the supposed triviality of their representation, becoming compositions that in their directness sometimes recall the decorative flamboyance of the 1950s. In Chramosta's form of representation lies a leverage that raises the question of the mutual interaction between abstraction as a (stylistic) phenomenon and aesthetics of decorative arts and crafts. The resulting undogmatic immediacy of the works enables viewers to approach the narrative strands and personal references inherent in them. Thus, the works gathered in this exhibition can also be read in their interplay as a diary or personal travelogue of a stay in Rome. The synergy of the "public" and the "private" is also inherent in the artistic work itself and the position of artists in society.

The materials, mostly left raw, such as clay and steel, are processed in production methods that are in part reminiscent of the techniques used to make jewelry, such as setting precious stones in gold or silver. Fabrication is also used to negotiate the status of the works in the exhibition space and their environment. Thus, many of Chramosta's works bear equal parts the attributes of set pieces of everyday life and urban space (e.g. fences and gates) as well as traits of decidedly classical art forms. It seems as if the mostly artisanal production methods balance the poles between item and object, turning quotations into imitations and, conversely, imitations into quotations. Decor as a design element also takes on a mediating role here.

In the case of the cylindrical test holes that spread out on the floors of the two mirrored rooms on the upper floor, fabrication has been outsourced and is, as it were, preceded. As found objects of public space, they link in a way to the title of the exhibition. "Miraggio" in Italian denotes a mirage. The artist thus refers to illusory landscapes and architectures, such as those created in pleasure gardens of the 18th century, but also found in the abandoned parts of the zoo of Rome, as shown in the titular video "Miraggio." In this context, then, the test drillings can be understood as an interrogation of the materialities of public space, but even more as an interrogation of realities. - Lukas Maria Kaufmann

Lukas Maria Kaufmann