Adam Shiu-Yang Shaw

Neither Parts, nor Spares

Project Info

- 💙 BPA// Raum

- 💚 Anna-Lisa Scherfose

- 🖤 Adam Shiu-Yang Shaw

- 💜 Mitch Speed

- 💛 Eric Bell

Share on

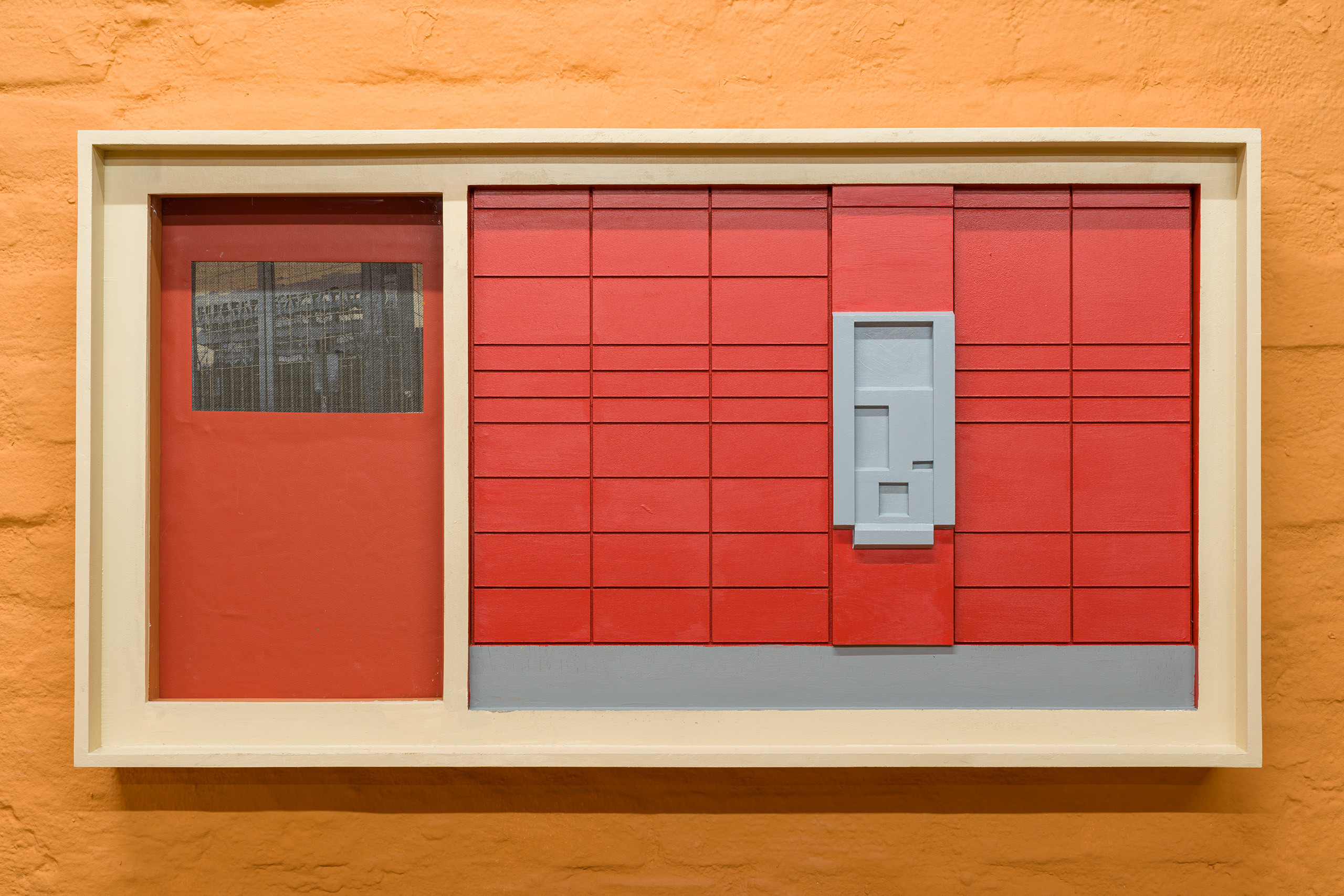

Parcels, 2022. Wood, MDF, chipboard, vinyl, inkjet print on canvas, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood glue, hardware.

Advertisement

Parcels, 2022. Detail view, sWood, MDF, chipboard, vinyl, inkjet print on canvas, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood glue, hardware.

Parcels, 2022. Installation view, Wood, MDF, chipboard, vinyl, inkjet print on canvas, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood glue, hardware.

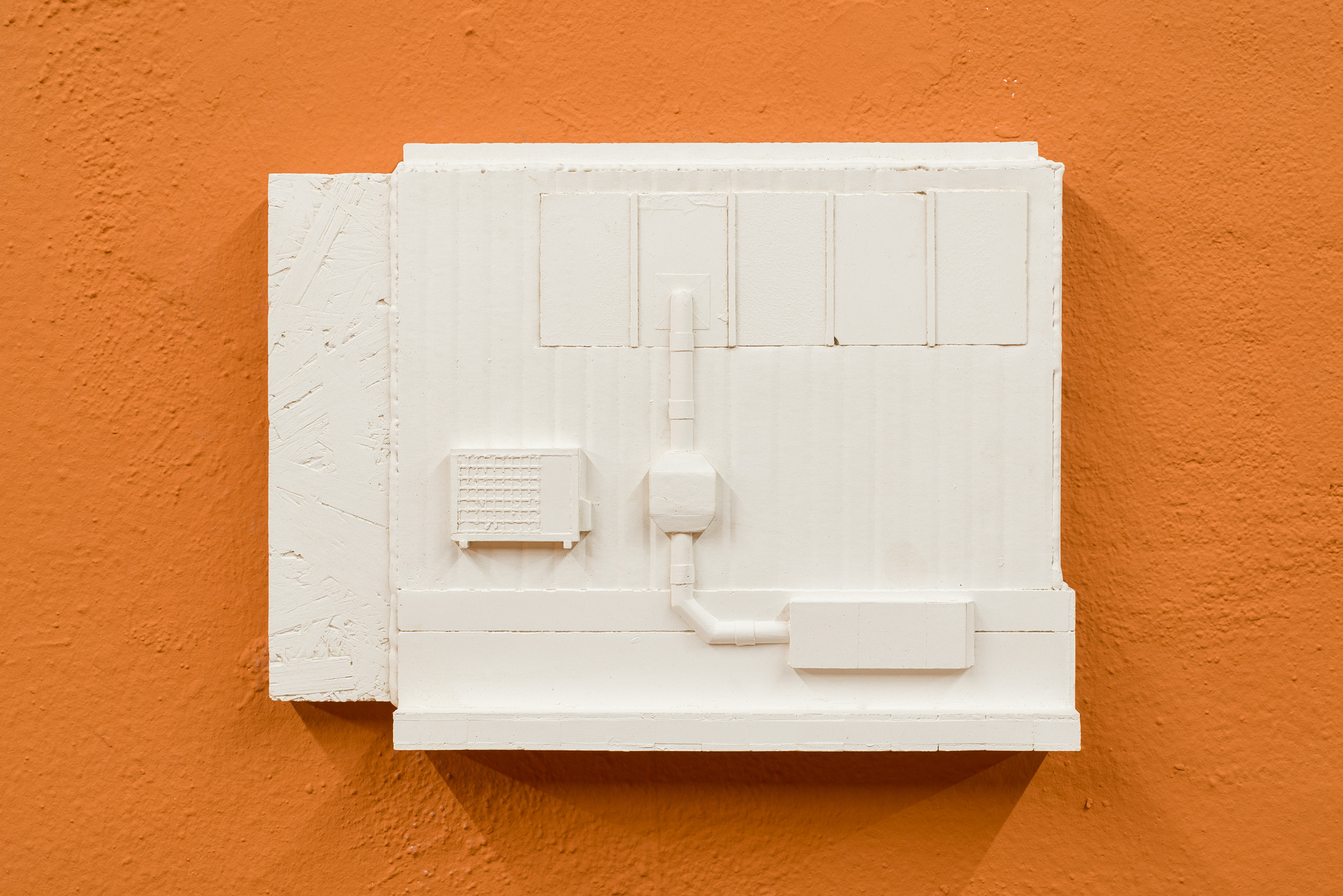

Exhaust, 2022. Plaster, steel wire.

Neither Parts, nor Spares, 2022. Installation view.

Hive, 2022. Wood, MDF, laminated chipboard, acrylic plastic, glass, plaster, concrete, found objects, speaker, field recording, light fixture, extension cable, enamel paint, acrylic paint, hardware, wood glue.

Hive, 2022. Wood, MDF, laminated chipboard, acrylic plastic, glass, plaster, concrete, found objects, speaker, field recording, light fixture, extension cable, enamel paint, acrylic paint, hardware, wood glue.

Neither Parts, nor Spares, 2022. Installation view.

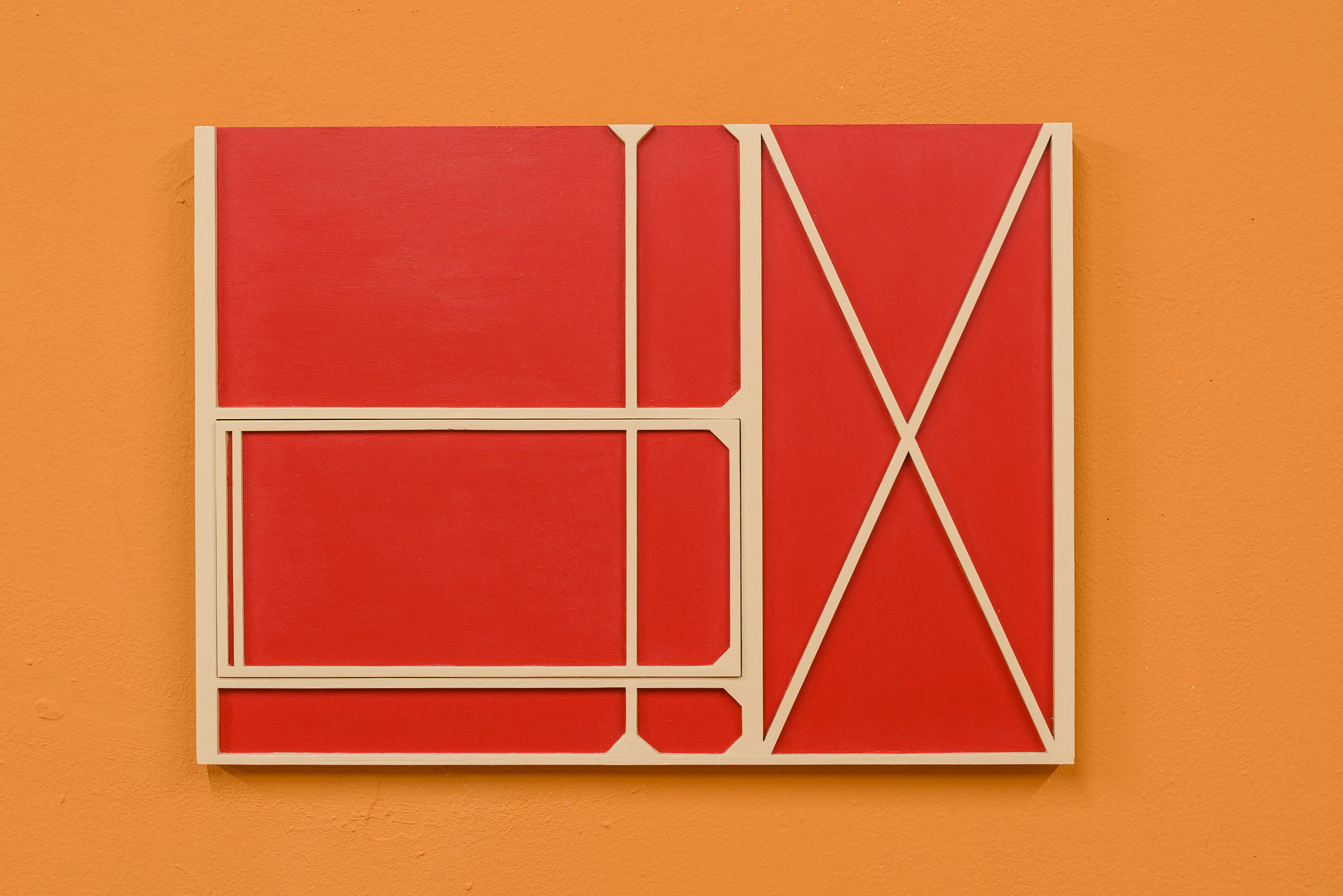

Reinigungshalle 2 (a), 2022. Wood, MDF, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood glue.

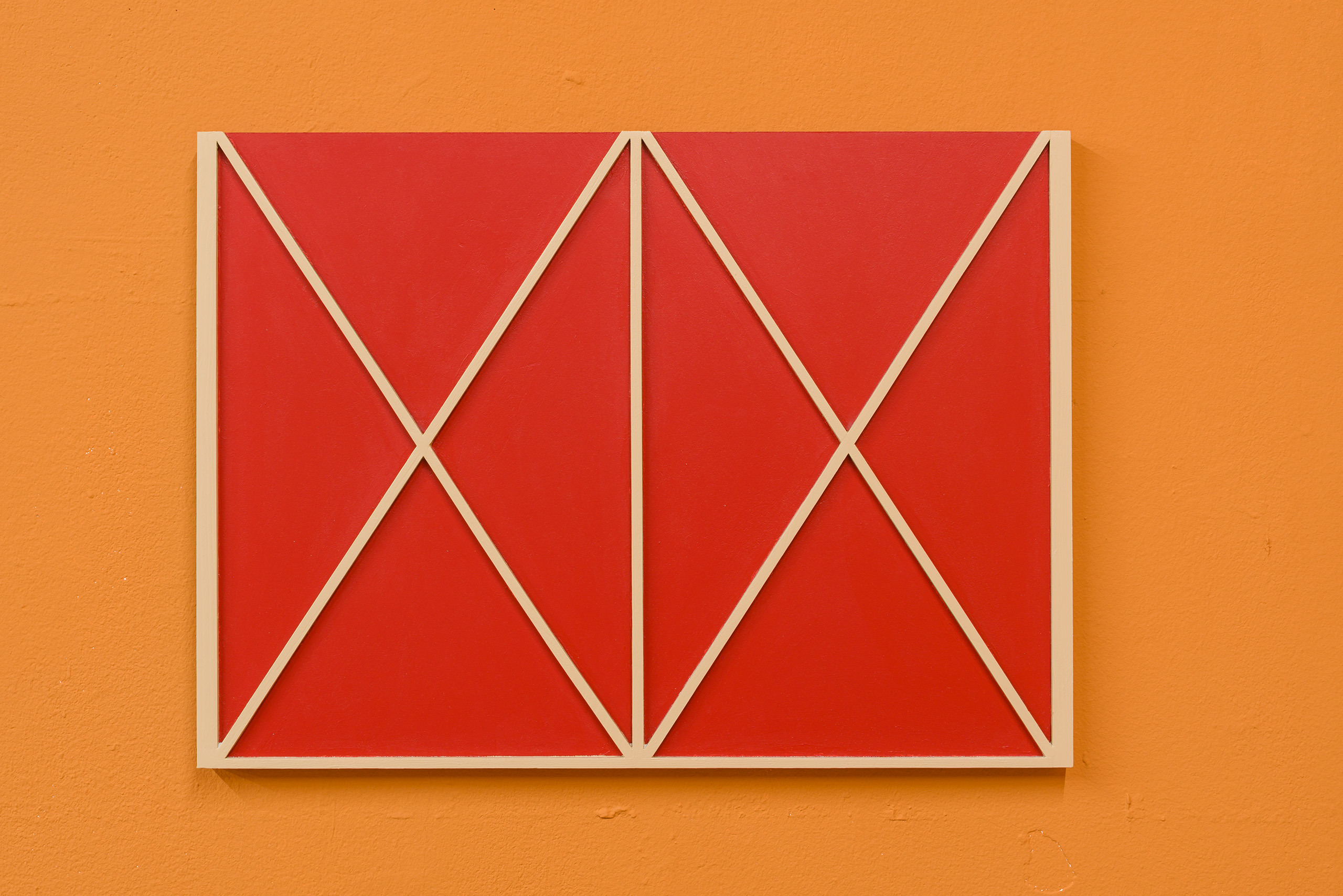

Reinigungshalle 2 (b), 2022. Wood, MDF, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood glue.

Levels, 2022. Wood, MDF, glass, light fixture, extension cable, enamel paint, acrylic paint, hardware, wood glue.

Levels, 2022. Wood, MDF, glass, light fixture, extension cable, enamel paint, acrylic paint, hardware, wood glue.

Neither Parts, nor Spares, 2022. Installation view.

Modules (Mariendorfer Hafensteg), 2022. MDF, wood, glass, ink transfer on deadstock paper, cardstock, tape.

Modules (Kfz Service Schwarz), 2022. MDF, wood, glass, ink transfer on deadstock paper, cardstock, tape.

Modules (Pförtnerhaus - Altes Gaswerk), 2022. MDF, wood, glass, ink transfer on deadstock paper, cardstock.

Grade, 2022. Wood, MDF, plaster, iron, acrylic paint, enamel paint, hardware, wood glue.

Grade, 2022, detail view. Wood, MDF, plaster, iron, acrylic paint, enamel paint, hardware, wood glue.

Neither Parts, nor Spares, 2022. Installation view.

Western Portal, 2021. Concrete, wax, steel wire. (left) Eastern Portal, 2021. Concrete, wax, steel wire. (right)

Ghosts in Plain Sight: Adam Shiu-Yang Shaw

by Mitch Speed

Sometimes I think that the central challenge of making art is balancing the necessity to engage the world with the unwieldy force of artistic inheritance. If art reflects life, as they say, these reflections appear through a prism of historically and subjectively determined artistic tongues. It is sacred, the historical nature of creative languages. At the same time, what is true of life is true of art: out-of-control ancestral reverence is the stuff from which cults are made. When art becomes a cult, its languages die, preserved by pseudo priests in a formaldehyde of hermeticism.

One thing to notice about Adam’s work is the plucky grace with which it negotiates this inherent risk of art. It is anything but closed off or self-serving. On the contrary, it’s entertaining how Adam interpolates recognizable aspects of our constructed and cultural worlds into his work. His sculptures are the black-sheep siblings of multiple art forms that, while existing outside of galleries, engage the world through collective experience and mythologizing, like the miniature displays of cities that can be found in municipal museums or that act as backdrops in community theatre presentations.

Created using wood, plaster, and medium-density fibreboard, Adam’s pieces elaborate sculptural renditions of the city’s curious architectural details into forms that flirt with abstraction. Sometimes they literally incorporate disembodied chunks of their subject matter, such as the salvaged panes of glass that have structured recent pieces. And so, although you can very clearly recognize the world in the work, it’s a version of the world whose innate strangeness and wondrousness—the gestalt of ostensibly utilitarian forms—is accentuated rather than occluded, as it usually is in the spaces of daily life, through which these phenomena swirl like phantoms in plain sight. Adam’s work holds the ghosts still.

Owing to the power of this effect, my appreciation for his sculptures has tended toward a wilful delusion that they are free from intergenerational influence, existing purely in present-time experience. To his credit, Adam reminded me of the precedents that have nourished his work and its attention to what a person might (risking condescension) call the city’s marginalia. We were riding our bikes through the area of Berlin surrounding his studio, a still-ungentrified, or perhaps lightly gentrified, mixed-use residential and industrial region just outside of the city’s core. This area contains several industrial lots and big quiet parks that are either lonely or peaceful depending on your mood. And it’s here where Adam has lately taken a large number of the photographs that function as reference material for his sculptures, a working method that he began years ago in Canada.

In this way, the present work interweaves personal and cultural histories. As we were chatting, Adam made reference to filial piety, a Confucian ethos of practicing respectful conduct vis-a-vis one’s parents and ancestry. This way of being is implicit within a set of Adam’s photographic material that is at once especially distant and especially close to home: the photographs taken by his mother in Fuqing, Fuzhou, and Hong Kong. Flying in the face of the patricidal Oedipal myth and against a wilful amnesia regarding one’s influences, this ethos touches his sculptures in general; they become altarpieces that serve the presence of multiple pasts inside every person and every voice.

Adam’s quasi-anthropological photographic method itself has ancestors in a tributary of late twentieth-century art that played an especially vital role in Vancouver (a city where Adam studied alongside a group of artists who are also now living and working in Berlin). Between 1969 and 1970, the Vancouver photographer Christos Dikeakos turned his camera to aspects of urban life that had not previously received much attention from artists. His Ruins series consists of straight-ahead, effectively uncomposed shots of scrappy industrial sites and residential houses that appear either abandoned or under construction. The designation of these sites as ruinous could be debated, since what the photos depict are also sites of production and of life. So, the series is really a thought experiment, one which situates urbanity itself—if not to say human society—as a destructive force.

The connection between Dikeakos’s Ruins and Adam’s work appears in this attention to the “ruinous” nature of the city, which is not only critical but imaginative and romantic. The photographs that nourish Adam’s sculptures likewise communicate a desire to experience civilization in the borderlands between past and present, daily life and industry, functionality and decay. This yearning has deep roots. It can be traced at least to the Romantic poets, and probably farther back still. In late twentieth-century Western art, it was most famously exemplified in The Monuments of Passaic (1967), the canonical series of photographs by American conceptual artist Robert Smithson, who also made work in Vancouver. Smithson’s series depicts the buildings and infrastructure of Passaic, a sleepy New Jersey city. The work’s mood is ironic sublimity. It’s about a need to find magic by escaping the confines of boring but smoothly functioning day-to-day reality, not by venturing to foreign lands but by searching the fraying margins of one’s home society. And although these works evade the ethnographic fetishizing of the Other, they still turn a fetishistic or at least highly imaginative lens upon the Other within Western society—the industrial, the impoverished, the working class, the run-down. Hence, the wry nature of both Dikeakos and Smithson’s titles.

Several decades later, with more earnestness than irony, Vancouver artist Marian Penner Bancroft combined this conceptual-archaeological approach to photography with sculpture. Her installation BLIND/MAT(T)ER (1990) consists of a group of facsimile freestanding blackboard structures and window-like panels angling out from the walls that, from edge to edge, all hold photographic prints of human-made tools and objects, as well as a clam fossil and dead deer. The verso side of each blackboard is covered with a graphite rubbing showing the texture of various surfaces in Bancroft’s studio. You can feel in this work a will to integrate physical contact into the space between the photographic gaze, which retains distance despite the most intimate intentions.

In one way or another, through various links of influence, these precedents have formed Adam’s language. The photographs that he draws upon are descendants of a specific anthropological-artistic photographic tradition. Whereas Penner Bancroft used graphite rubbings to bring life’s texture to bear on photographic space, Adam works the surfaces of his photographically informed sculptures into synthetic patinas, which imply time’s passage while keeping us firmly grounded in a space of make-believe illusion. A singular point of convergence within this tradition, Adam’s work retains an uncanny hold on the crumbling present.

Adam Shiu-Yang Shaw (born in Edmonton, Treaty 6 territory, Canada) works between Berlin and Edmonton. He received his MFA from The Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm (2016), and his BFA from Emily Carr University of Art + Design (2013). Shaw has recently exhibited at Wschód Gallery, Warsaw (2021) and KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2021) and in 2023 will have presentations at Towards Gallery, Toronto, Wschód Gallery, Warsaw, and Echo, Cologne.

BPA// Berlin program for artists is an artist-run mentoring program founded in 2016 by Angela Bulloch, Simon Denny and Willem de Rooij. It facilitates exchange between emerging and experienced Berlin-based artists. The program is funded by Lotto Stiftung Berlin.

Mitch Speed