Monika Stricker

Natürliche Enthüllung

Advertisement

Has our art been too exhausted by sophistication?

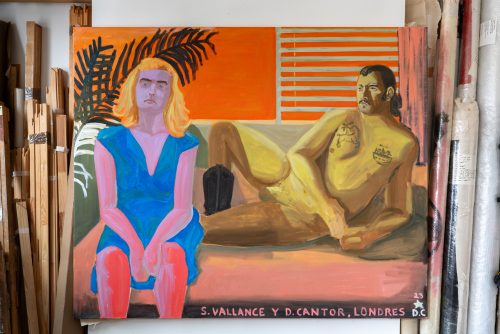

R.B. Kitaj

The depiction of a monkey actually always stands for something else,

especially in paintings. Most of the time, monkeys act as a

distorted picture of mankind, they articulate the tragic dimension

of human existence, of life as a cultivated animal. Clearly, Rococo

singerie painting only worked satirically because apes are not too

distant from us humans in terms of evolutionary biology, which draws

attention to the subtle differences. And this is, in a way, the precondition for the exhibition "Natürliche Enthüllung", with which Monika Stricker continues her engagement with the scrotum, which has now been going on for several years. At first, it was probably driven by the shape, a sculptural interest in the unshapen vulnerability of the scrotal sac, this flap of skin that permanently

outlines what it actually intends to protect. Perhaps her curiosity was also aroused by the fact that this organ, which is most closely associated with the performance pressure of the male body, would not withstand any pressure itself. But every pictorial occupation with primary sexual characteristics, is layered with questions of gender identity, whereby issuing into a social climate that is heated concerning this matter, everything soft, vulnerable, and querying threatens to slip to the margins of the discussion. That is to say, that looking at scrota evidently does something to us, an action most of us don't take on a daily basis. We don't even have the language and social space to talk about something like the fragility and impressions of scrota without irony, let alone find the plural form of scrotum without consulting a dictionary. And I think this is one of the central points that made Monika choose this subject (apart from certain studio processes to which we non-producers principally have no access to), that we may be forced to enter certain spaces of engagement that we otherwise tend to avoid. The slight shift to monkeys and their dangling scrota now offers the opportunity to revisit Stricker's interest in the subject. After all, the change of species goes hand in hand with a casual, almost provocative presentation of the scrota. For starters, this offers us

excuses, because it is no longer one hundred percent about us, and statements can again be backed up by a wink. Perhaps this relief, which arises through the distance to ourselves, since now the topic apparently is monkey’s balls, leads to the actual subject matter of Monika's pictures. A relief that results from an absence of shame. On the one hand, because the monkeys behave shamelessly as a matter of course. On the other hand, because of the levels of contemplation and conversation that can now again be completed supposedly without accident or shame. And it is precisely because the monkey is off our backs that the eternal indicator of humanity, shame, is put forward as the actual subject of Monika's paintings. Formally, the vulnerability of the testicles stored outside the body in a sack of skin corresponds to the feeling of shame. And the depictions of feet also indicate a part of the body that is genuinely connected with being human and walking upright, but is nevertheless dismissed as misshapen and disgusting in most cultures. If one thinks further about this connection between humanity and

shame, then perhaps the primate scrota no longer represent mere evasions of a confrontation with shame, but perhaps also a bridge and modes of conversation for such objects occupied by fears and compulsions. Or, more generally, for finding a way towards attitudes and discussions on substantial human issues which we have somehow forgotten how to talk about. You can tell from the small, intimate pictures that someone did not make it easy for themselves to arrive at them. Behind each one, we suspect a handful of images that have been discarded because they were too misleading, too directive, too inaccurate, or too self-assured. Normally, images are expected to withstand the gaze, to bear their own exposure. But shamefacedness

is causally related to being exposed, unveiled, looked at, which is why Monika had to apply a different sensitivity, which comes across more or less, depending on the person opposite. But because she has long since left behind this internalised rogue language of art, one senses again the tingling uncertainty of the open terrain, which demands something of all those involved, it always carries the possibility of failure, but most importantly also a few promises.

Moritz Scheper