Rebekka Benzenberg

GODSIBB

Project Info

- 💙 Galerie Anton Janizewski

- 🖤 Rebekka Benzenberg

- 💜 Sebastian Peter

- 💛 Hans-Georg Gaul

Share on

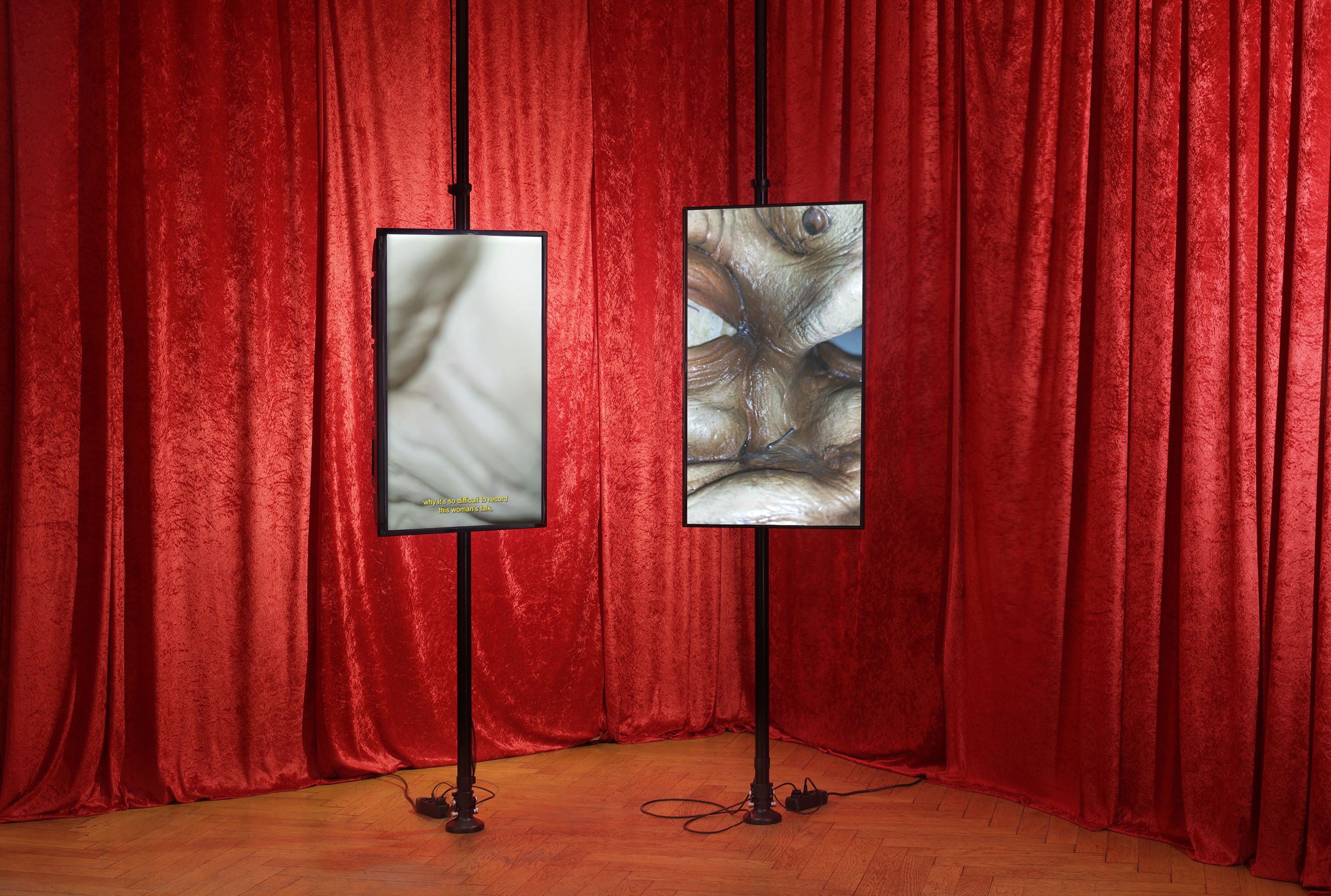

Rebekka Benzenberg, in my kitchen, 2022, 10 min two channel video, edition 1 + 1 AP

Advertisement

Rebekka Benzenberg, the gaze, 2022, 220 × 220 x 50 cm, mixed media installation

Rebekka Benzenberg, don’t you get tired, 2022, 3D printed resin, 40 x 40 x 25 cm

Rebekka Benzenberg, gossip girl, 2022, mixed media installation, 185 × 200 × 200 cm

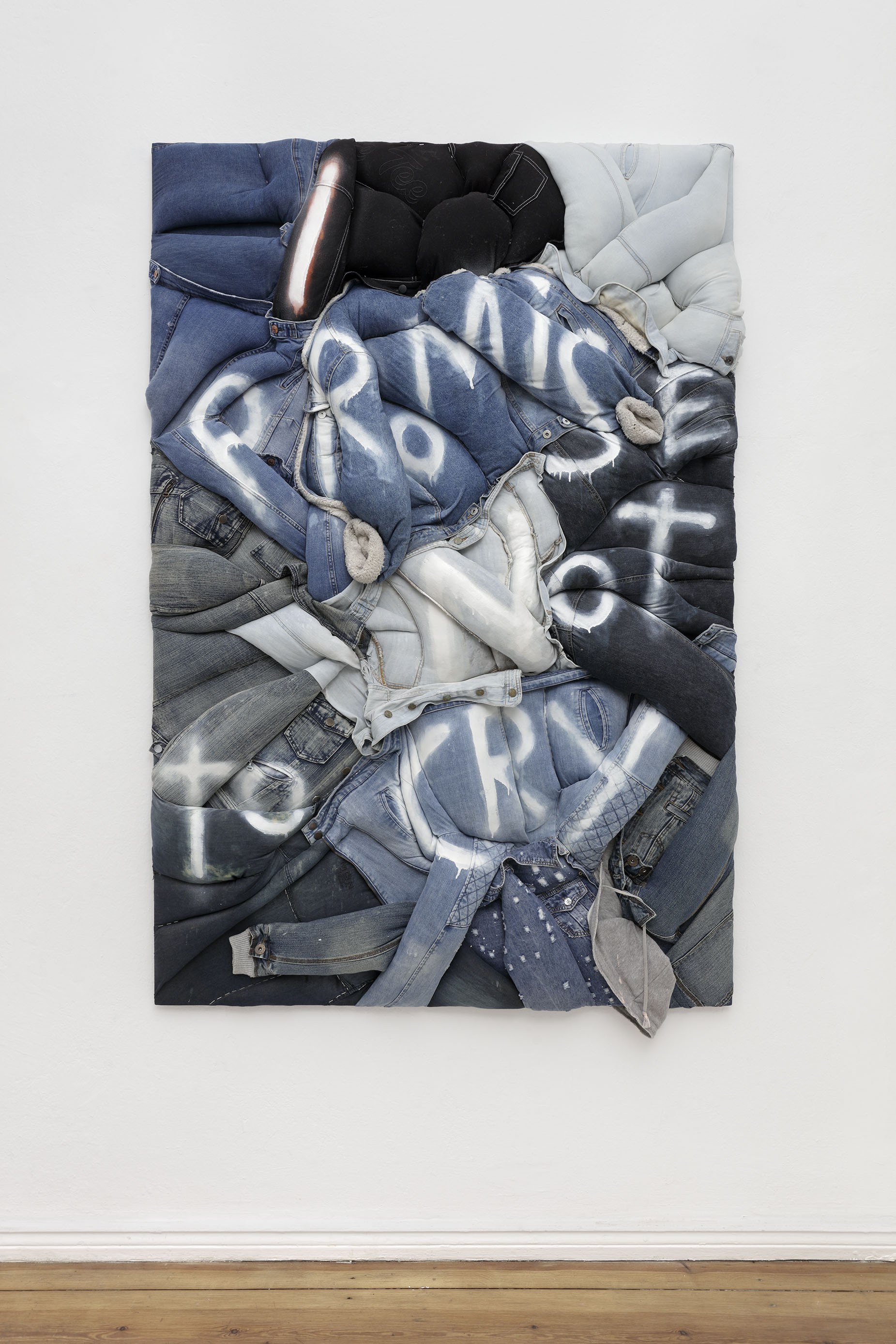

Rebekka Benzenberg, I promise not to cry, 2022, 180 x 120 cm, mixed media

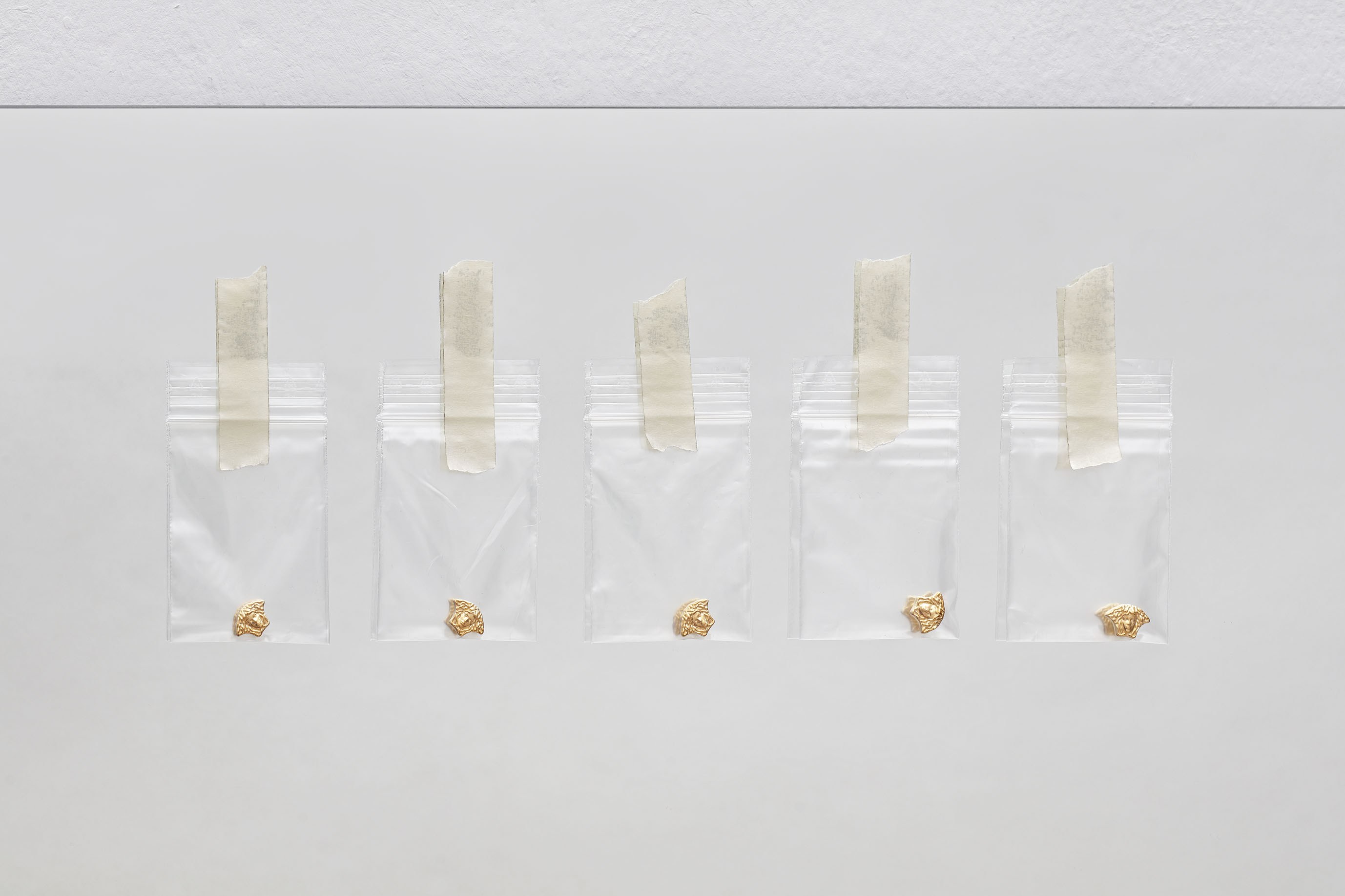

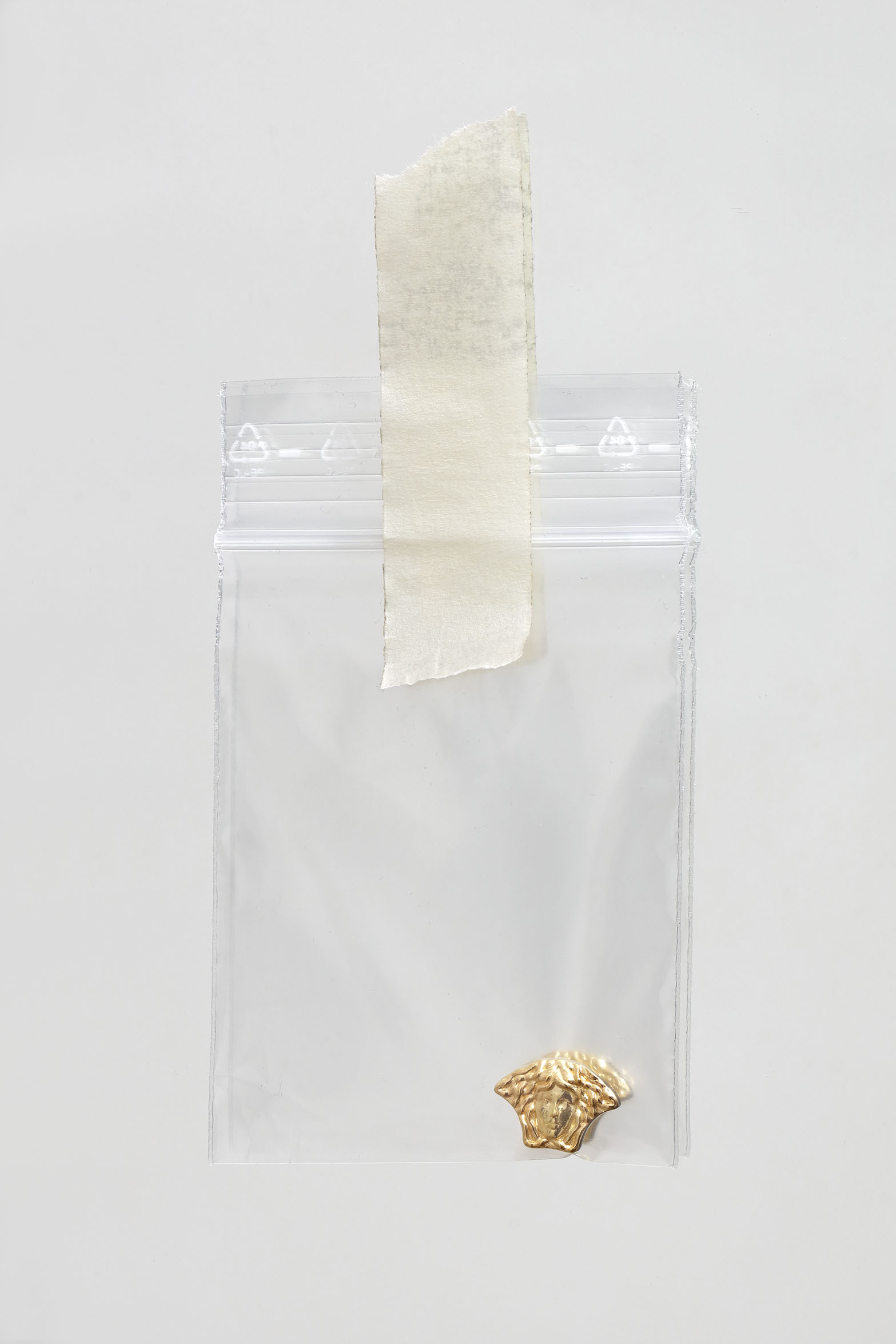

Rebekka Benzenberg The Laugh of the Medusa - solid gold edition, 2022 1,5 x 1,5 x 0,3 cm gilded bronze extasy pills edition of 10

Rebekka Benzenberg The Laugh of the Medusa - solid gold edition

Rebekka Benzenberg, the gaze

Rebekka Benzenberg, the gaze

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Rebekka Benzenberg, gossip girl

Rebekka Benzenberg | GODSIBB

Opening: 10.11.2022

Exhibition: 11.11.2022—14.01.2023

Rebekka Benzenberg’s second solo exhibition at Galerie Anton Janizewski is titled GODSIBB and assembles a new group of works that explores the far-reaching cultural history of misogyny through the use of media as diverse as drawing, 3D printing, video, and installation.

The artist’s research originally began with a critical interrogation of the Carnival: why do we still take shelter in momentary anonymity and the illusion of equality through the aid of costumes? Through a preoccupation with the material of mummery, which only appears innocent at first glance due to its colorful synthetic appearance, however, an artistic examination ultimately unfolded that traces expressions of misogyny from the present back to Greek antiquity. Based on the hideously distorted visages of the witches’ masks that appear at carnivals and at Halloween, the artist has undertaken an almost detective-like quest for rudiments of multiple transformed motifs of misogyny and traced them back to their roots.

Guided by feminist theory and an analytical sensitivity to pop cultural phenomena, it is no coincidence that among some of the most reproduced female figures she has made her find. A walk through the exhibition space confronts us with omnipresent figures such as Medusa, whose cruel history (being raped, turned into a monster, and finally killed) has been obscured and overwritten by her boundless iconifications for the sake of satiating our desire for delightfully gruesome figures. Lined by the red velvet of cinematic and theatrical palaces, Medusa’s head emerges here as the result of 3D prints in the form of a remodeled ecstasy pill. In accordance with the original story affixed to a mirror, the face on the two-sided pill glares at us, copied many times over and individually packaged. The head of Medusa, meanwhile, having arrived in club culture, is fixed as the end point of an unmanageable chain of appropriation through the material rendering in robust plastic, and is placed into a new context through its transformation into an exhibition piece.

Only a few steps further, the abandoned scenery of a stage-like room opens up. As if we had gained access to her intimate rooms, we discover the discarded clothing of a defamed stranger in a bathroom and a dungeon hung with drawings and text banners from the inside. Her tow robe, pieced together from several denim jackets, is named after the TV series “Gossip Girl” and establishes the connection to the exhibition’s title (1). A series of organic cut-out drawings on nettle fabric has been attached to it much like the band patches on the frocks of music fans. The illustrations, taken from reference books, depict chains and torture devices as well as masks of shame that were used in the 17th century to punish so-called crimes of honor, such as gossip, with public scorn.

Transferred to the patches and attached to the denim material of everyday fashion, the images here become historical brands of female oppression. Transposed from a 3D print into the physical present, the mask laid aside in the sink finally permits us to visualize the idea of a woman removing her grotesque face covering before going to bed after a day of ridicule.

(1) The word “gossip” has been used since early modern times to describe empty, lurid talk and, with its feminine connotations, devalues conversations between women in particular. In its origins, however, the

Old English word meant “godsibb” godmothers or a good, usually female friend.

After we have searched the private chambers of the exposed with a voyeuristic gaze, we encounter a video work at the end of the exhibition that examines the witch masks initially mentioned in a jerky tracking shot at close range. The gloomy sound that lingers over the two-channel installation can be suggestive of the many transfiguring witch stories from movies. Yet, together with the previously seen drawings of the torture devices, associations with the crime of witch hunts are evoked. The narrative framework of the work is set by a conversation the artist had with a friend about self-experienced injustices in the art field. The reflective final part can be read in inserted subtitles, which deals with the impossibility of publicizing this kind of very intimate conversation between women. Consequently, it reappropriates the concept of “gossip”, which has been displaced for centuries, in reversion to its original positive meaning, and marks it self-empoweringly as a safe space.

Without diminishing the urgency of the research displayed throughout the exhibition space, Rebekka Benzenberg manages to lift the overwhelming weight of the subject. The works intellectually informed by history books and essays are complemented by a multitude of quick drawings and text works with impulsively selected song lines. Taken from her favorite songs and transferred to denim and nettle fabric, we encounter the catchy phrases on walls, kennels, and freestanding in space. As an expression of one’s attitude to life with a simultaneous offering of identification, the music serves here as a storehouse of emotion and, after all, provides hope and courage for a better future.

Translation: Lena Stewens

Sebastian Peter