Jonathan Bréchignac

La Caverne

Advertisement

At the crossroads of syncretic archaeology and the most futuristic digital multiverse, Jonathan Bréchignac's exhibition is presented as a dreamlike cave, at once unknown and familiar, strange and yet soothing, the memory of a past civilization or the refuge of another hidden one.

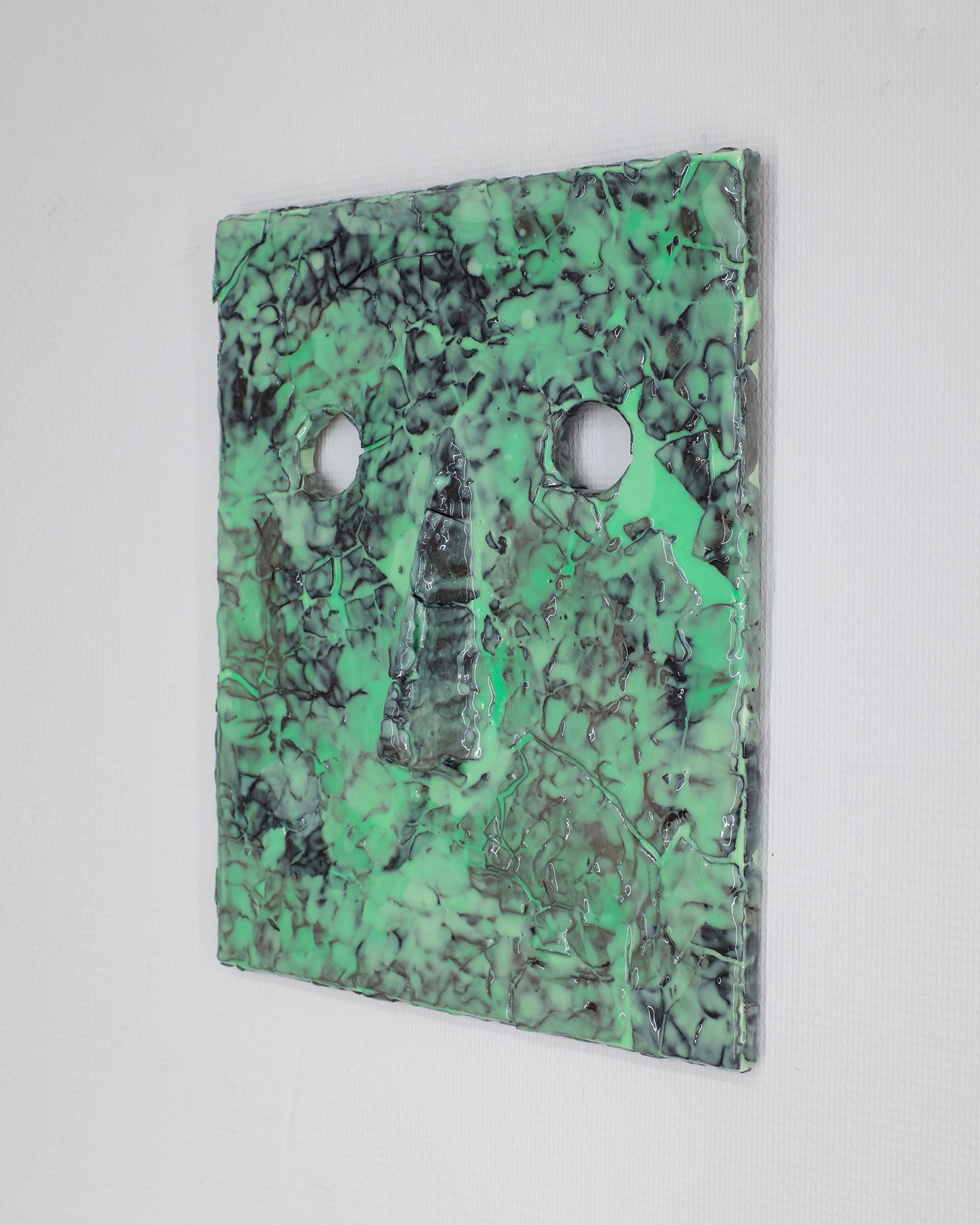

Keeping the entrance, well camped on their two feet, the sentinels face us. These protective geniuses, resembling Egyptian sphinxes or Assyrian bulls, symbolize the step of a door, both physical and symbolic, the entry to a sacred or at least precious environment, another world. Visibly underground, this space has seen snails and mushrooms grow on their faces - reminding us of something shamanic, the experience then becomes almost initiatory. A pill is given to us, mineral and herbaceous, to symbolize the cave, and the psychotropic, a journey of the body and the spirit. There is the matter which, frozen, is flowed on their faces. There is green. Green everywhere.

Representing a form of balance and rebirth while referring to the synthetic, even chemical, the color green conveys many symbolic ambiguities. Here, it comes from an experience and an encounter: resulting from a dye test for silicone, it marks Jonathan Bréchignac by all its ambivalence, its strangeness, both reassuring and disturbing - a synthesized naturalness - of an almost phosphorescent character which lends itself well to the depths, to the cave and all its mysteries, while evoking the green backgrounds of cinema, preparatory surfaces for the projection of our imaginations.

Once inside, we discover many green stones and white concretions among a campfire, the first space of sociability, the birthplace of our exchanges on politics and philosophy, stories that link and divide us, and other collective narrations. In the center, a totem: on a concretion, three bottles, one representing water, the second gold, the third stone, and three primordial elements on which the quest for the philosopher's stone can rest in alchemy. The reference to alchemy refers here to a form of syncretism between science and belief, to one with two faces. The three bottles support a large stone topped with a hat on which mushrooms have grown, a reference to the clothed stones that can be found in the ancestral cults in India and Japan. Named Spiritus Mundi, from the name "universal fluid" associated with the color green in alchemical thought, it results in a synthetic totem where cultures mix, perhaps the residue of a forgotten or foreign world.

At the bottom of the cave is a large fresco. An arch, under and around which positive and negative forces unfold, which we sometimes recognize - pieces of cave paintings, animals, food, an Egyptian goddess, the Greek Gorgon, the Sumerian monster Huwawa - and yet which escape us. Multiple known and forgotten legends that have inhabited various eras and continents, here gathered and unified in a form of continuity: a wall to group all our mythologies.

Everywhere around these structural elements, there are small votive statuettes between prehistory, Egyptian and pre-Columbian art, a fountain where a quasi-organic juice stagnates, capsules of laughing gas, remnants of past cults and dances, an ambient perfume - something wet, cavernous - oscillating between natural and synthetic, just like the sounds that also fill the space with their ambiguity.

As we enter Jonathan Bréchignac's fantasy cave, we discover a complete work of art, a complex proposition that stimulates all our senses to immerse us in a space that plays with our familiar references. It is a place that is frozen and yet in movement -the resin evolves gradually, and the plastic also seems to be alive- in constant balance between Plato's cave, Dante's Inferno, cave paintings, an archaeological site, and a futuristic, almost digitalized space. It is thus a syncretism of our gathered memories that can lead to another history, a parallel universe that would reform our reality by mirror effect and would see the hunter-gatherer and the artificial intelligence meet in the same refuge. There is something of an awakening in this exhibition, of a shock, propelling us to search in the underground world - the physical and the mental - inside ourselves, in the depths of our learned beliefs to perhaps forge others, at a time when it has become necessary to recast our imaginations.

Grégoire Prangé