Sophia Domagala

Heaven and Hell

Project Info

- 💙 Marburger Kunstverein

- 💚 Michael Herrmann

- 🖤 Sophia Domagala

- 💜 Maximiliane Leuschner

- 💛 Fenja Cambeis

Share on

Advertisement

At first, there was a pair of hands. One placed protectively over the other, holding each other tenderly. With Hände [Hands], 2019, Sophia Domagala registered the memory of the intertwining of hands: first sculpted from wet, earthen clay; then fired twice, burning in hell, and glazing in heaven, before solidifying into an eternal embrace.

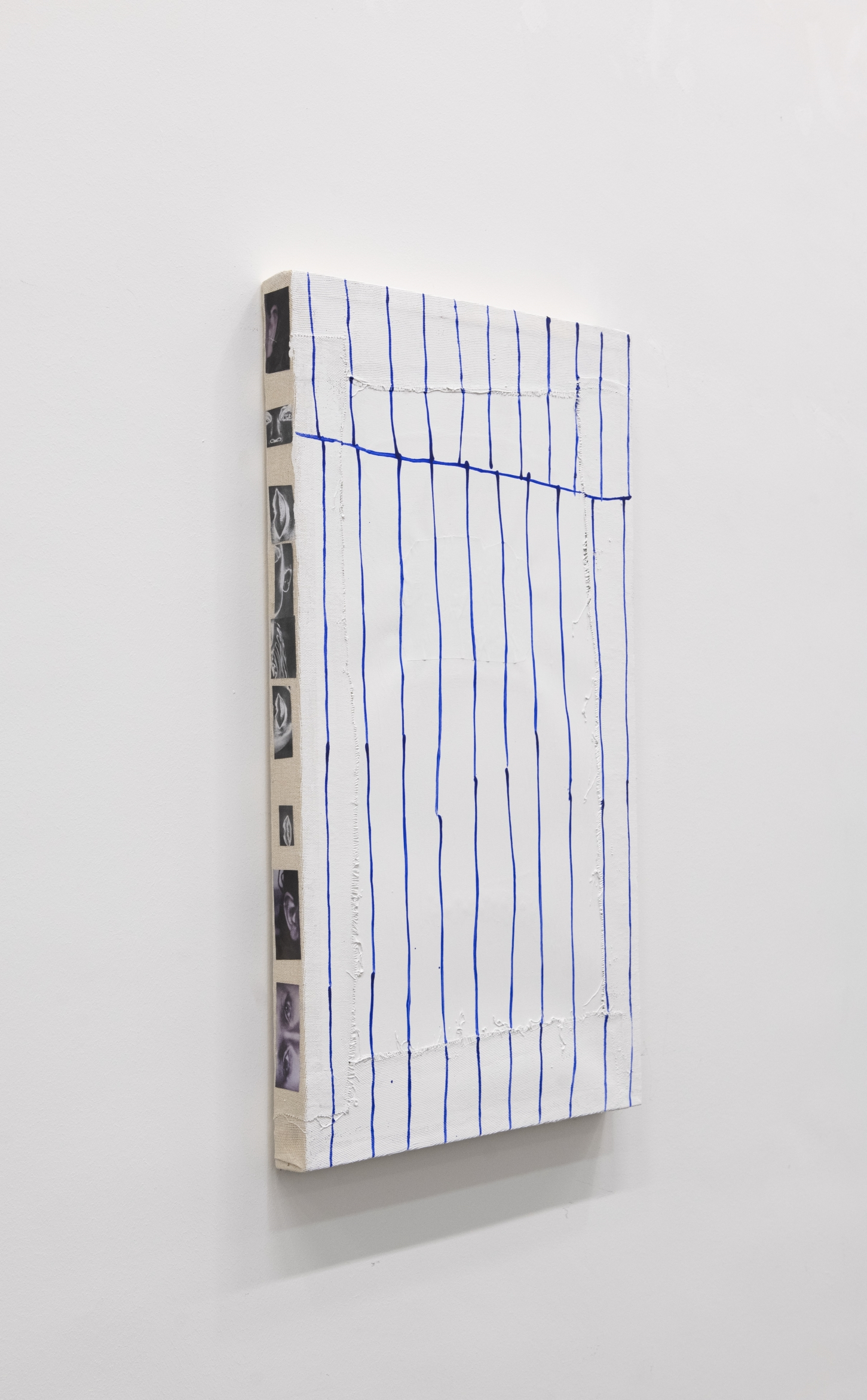

In 2020, these hands developed a life of their own. Fine lines appeared over notebook pages, photographs, prints, and jeans. Always extending from top to bottom, the same small gesture being repeated infinitely, meditatively. With intent—and yet, without a ruler. Some lines were coherent, others stopped along the line. Cracks and ripples started to appear. Sometimes, a second colour traced the movement of the first. But ‘where to ?’, you will ask. For a line, like a point, is elusive. It’s a fact of location, not a form in itself.

In “Heaven and Hell,” we encounter a little more than fifty of these linear evocations, mostly made up of medium-sized acryl and denim paintings that line the two floors of Marburger

Kunstverein. They appear playful, tinged in their Toblerone yellow, Wrigley’s green and Hubba Bubba pink. While delving into the scents and memories of our childhood—those of our favourite sweets, chocolates, and bubble gums—we realise that Domagala gives us not paintings, but the emotions and memories saved from books, photographs, and other narratives.

There are, for example, the dried rocket cress and St. John's wort flowers in Lines over Flower, 2022; the knickers in Panties over Lines, n.d.; or the flower-shaped cut-outs from Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in Light System 02_22, 2022. While Lines and Flower, 2022, evokes ox-eyed daisies and the fortune-telling “He loves me…he loves me not…”-game of our youth. Here, the desire to preserve something meaningful prevails. Pressed between two pages of a book, like a makeshift herbarium file, meaningful moments stay with us forever, quite literally touching us with their haptic format, rather than perishing in overcrowded image folders on our smartphones.

Then, there are the jeans, sewn together rather than piled up on a chair, in the series Lines over Jeans. Reminiscent of Ann Brashares’s novel series, The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants (2001), their visible stitches and embroidered surfaces reveal the wound scraps, the bittersweet moments interwoven in the fabric of our lives.

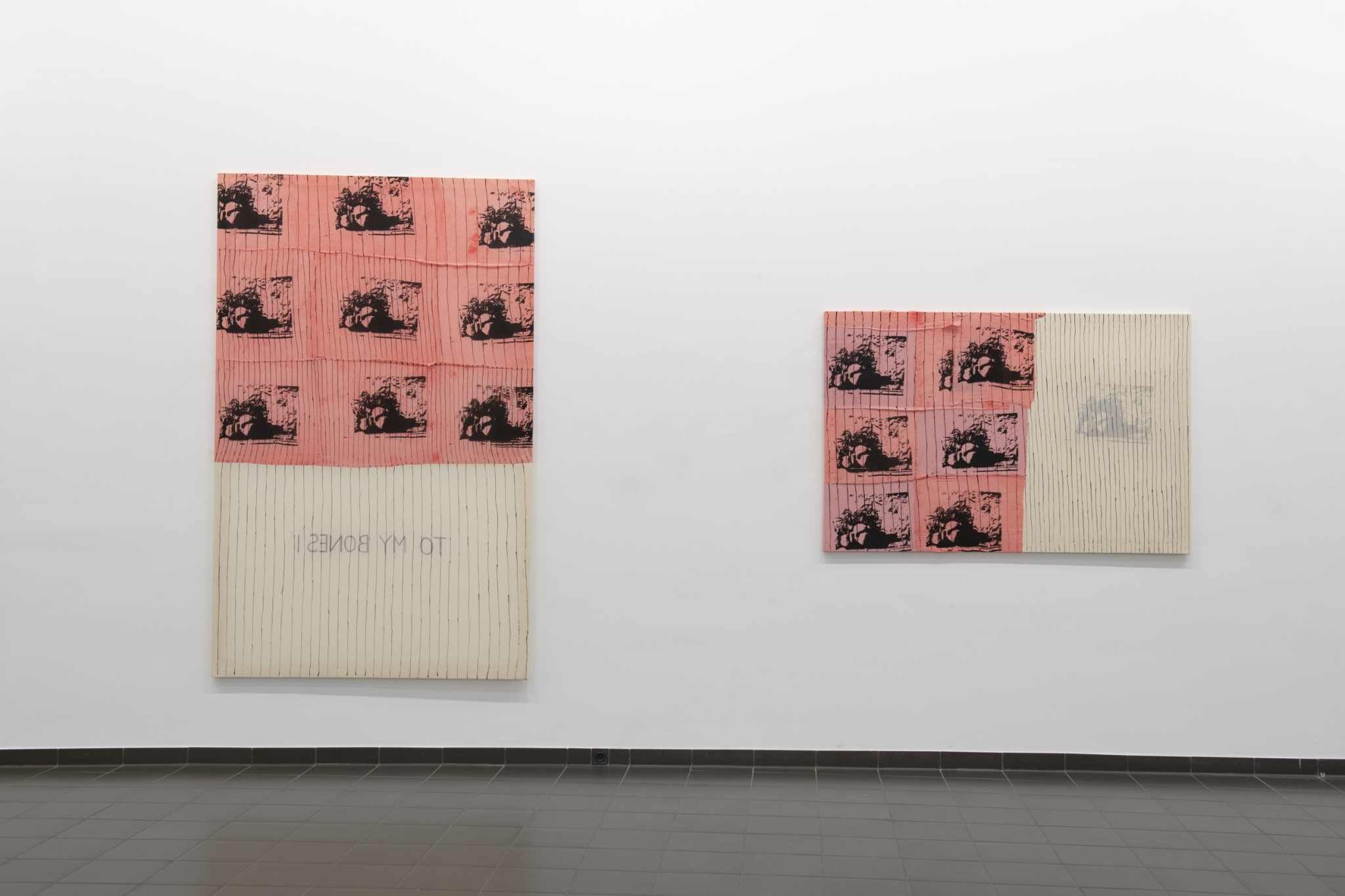

Meanwhile, in Lines over Big Moments II, 2022, Domagala has incorporated four (independent) text passages: ‘Writing after I,’ ‘Only then do I,’ ‘Catch fire I,’ and ‘To my bones I’, from Clarice Lispector’s final novel, A Breath of Life (Pulsations) (1978). Like Olga Borelli who structured and organised the mountain of fragments left behind by the Brazilian novelist after her passing, breathing new life into her words, we need to read between (or rather beyond) the lines in Domagala’s paintings to make sense of the clues she left behind.

And indeed, a writerly spirit emanates from the exhibition: some of the paintings remind of loose, unstrung notebook pages or extracts thereof, like Light Systems I, 2021. Some of these scraps, such as Light System V, 2021, appear to be speckled with coloured pen doodles bleeding through the pages. Think of French philosopher Roland Barthes who, in The Empire of Signs (1983), mused, ‘where does the writing begin ? where does the painting begin ?’, but also of Joan Didion and her essay On Keeping a Notebook (1968). For the American journalist and novelist reminded us that the process of note-keeping is often of an impulsive and compulsive nature and not necessarily of factual value.

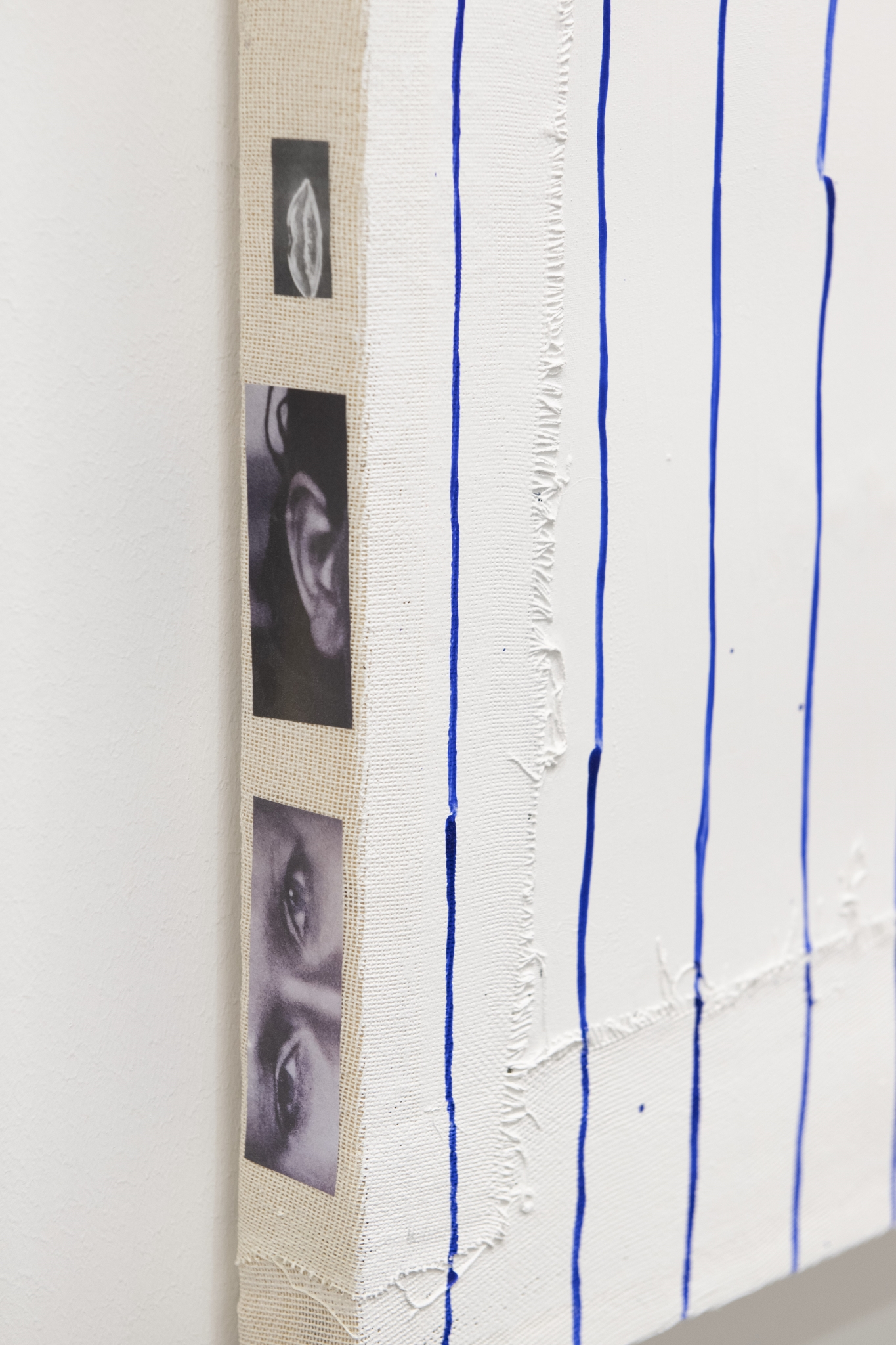

The second clue is the many photographs that appear throughout the show: one of the first paintings in the exhibition, Lines and flowers on Sieverding, 2022, establishes a link to Katharina Sieverding’s self-portraits. Known for her extreme close-up formats, as well as silhouette and contrast settings, the German photographer makes use of abstraction to achieve both a familiarity and a distance between herself and her audience. Similarly, Domagala often obscures, showing us only extracts or scraps and never (or rarely ever) revealing the full picture.

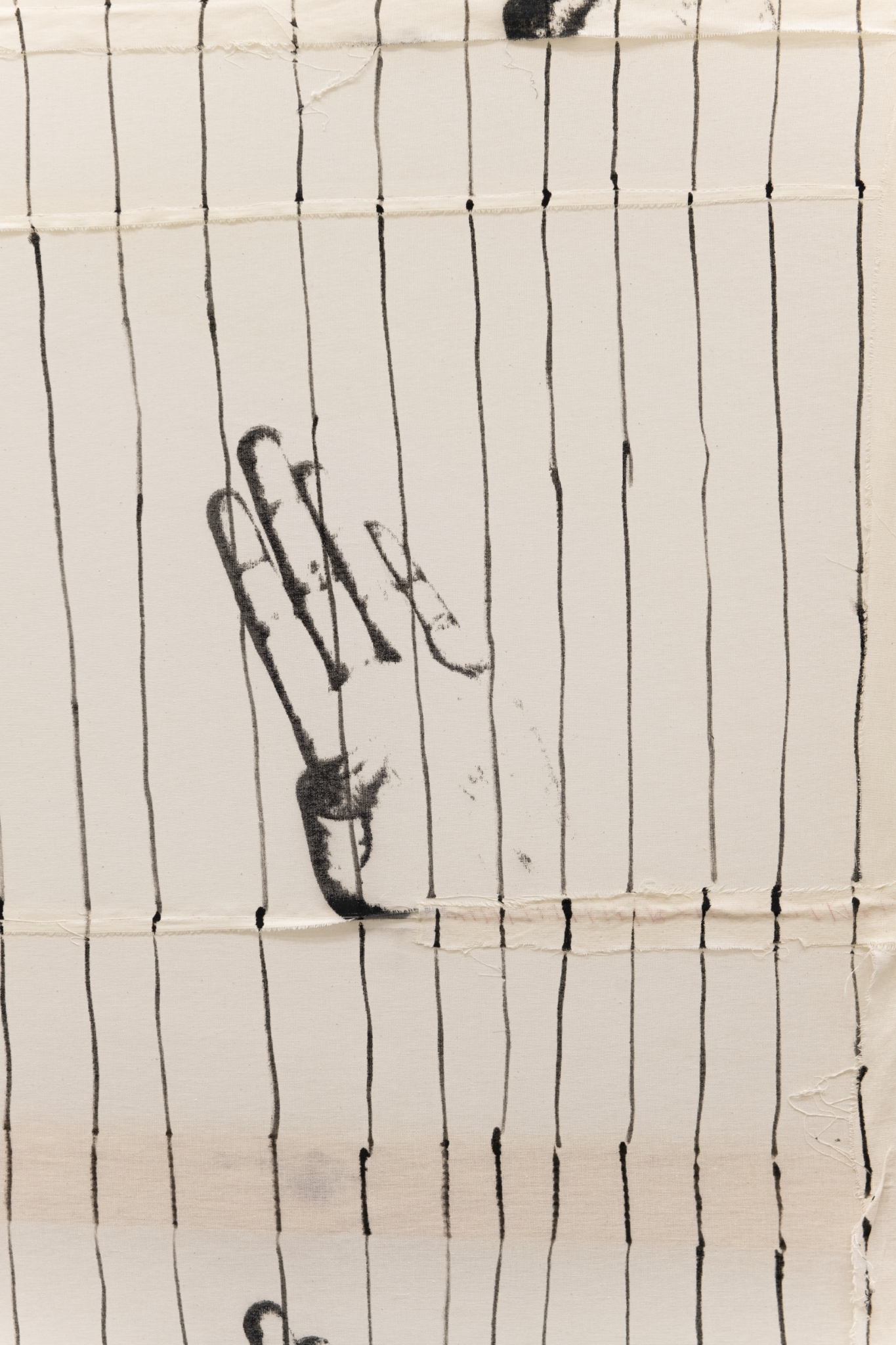

Meanwhile, Domagala’s more recent series, like Lines over Hands, 2023; Lines over Father and Child, 2023; and Lines over Child’s Face, 2023, have been inspired by the Depression-era photographers Dorothea Lange and Lou Bernstein and their intuitive approach to documenting and registering emotions and feelings. Lange, for example, often roamed the streets of Manhattan during her adolescence and learned to observe without intruding. For Lines over Hands, Domagala has appropriated the hand gesture of a Legong dancer in Java that Lange took in 1958 while travelling in Indonesia with her husband. Legong as a dance form thrives on an intricate movement of the hands and fingers: young girls learn the pointing of fingers, the twisting, the turning, the waving, and the contorting of hands from an early age to ensure that these specific poses burn into their muscle memory. In Domagala’s seven prints, Lange’s hand establishes a link to the gestural hand movements while screen printing: when the hand moves over the printing press from top to bottom, like the lines over some of her paintings.

Think of Clarice Lispector who, in Água Viva (1973), mused, ‘I write in signs that a more a gesture than a voice. All this is what I got used to painting, delving into the intimate nature of things. But now the time to stop painting has come in order to remake myself, I remake myself in these lines. I have a voice. As I throw myself into the line of my drawing, this is an exercise in life, without planning. The world has no visible order and all I have is the order of my breath. I let myself happen.’ And this is where Sophia Domagala has drawn the line.

Maximiliane Leuschner