Jobst Meyer

Konstruktionen der Neunziger

Jobst Meyer: Konstruktionen der Neunziger, 2022. Installation view, EXILE Erfurt

Advertisement

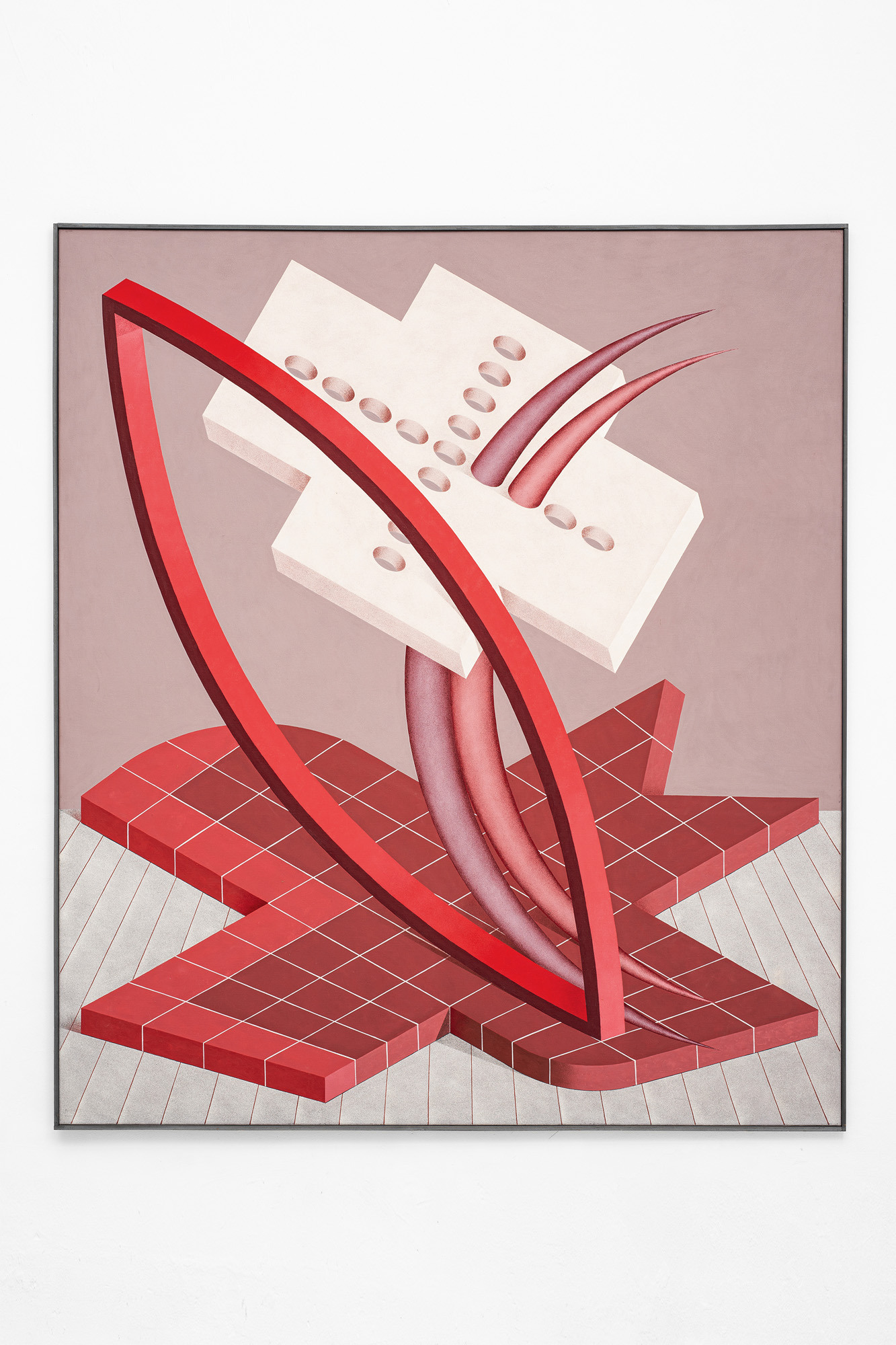

Jobst Meyer, Konstruktion mit Lochkreuz und Monden, 1990, tempera on canvas, 200 x 175 cm

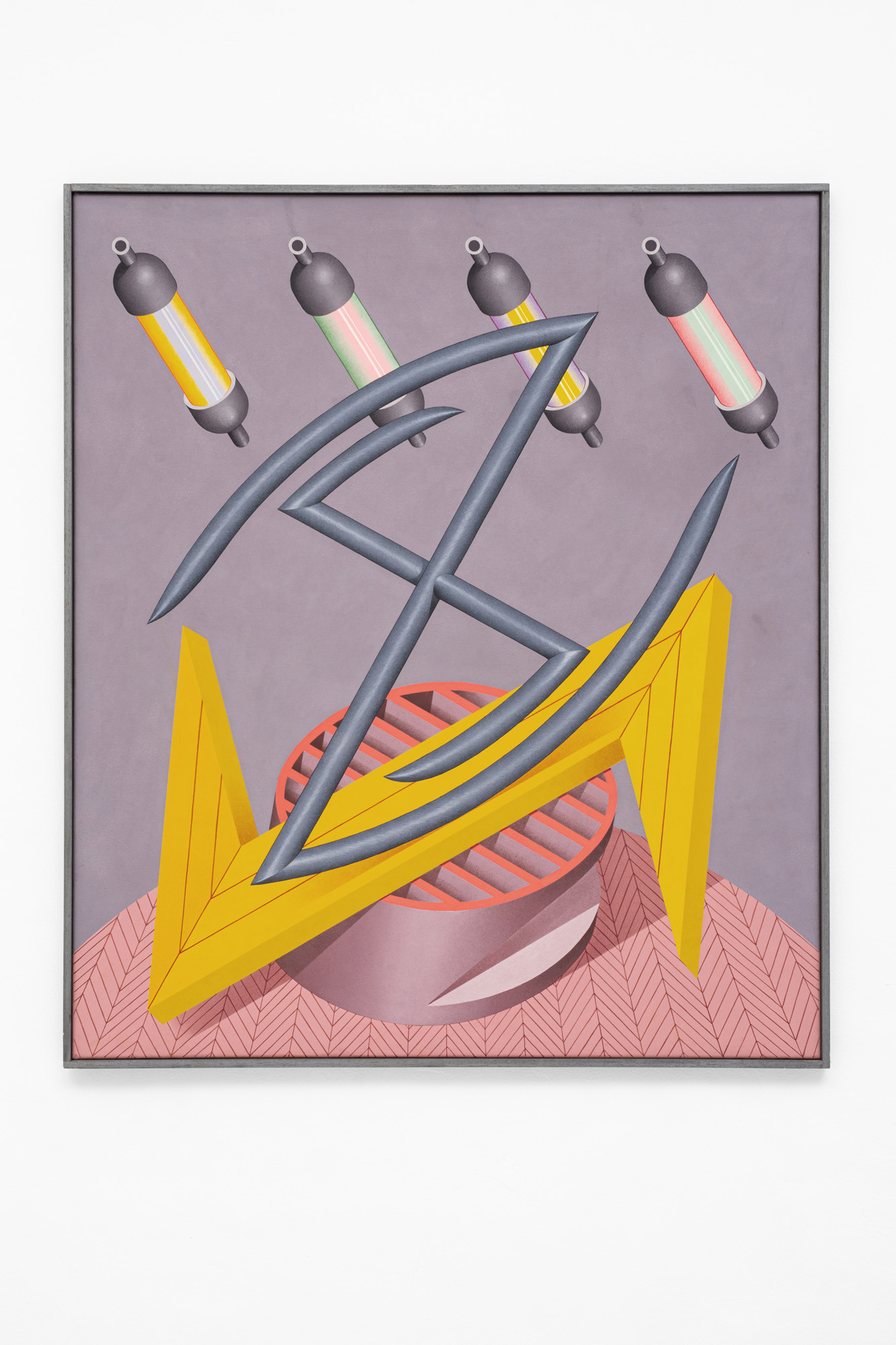

Konstruktion auf Schaukelkreuz und Lampen, 1999, tempera on canvas, 110 x 95 cm

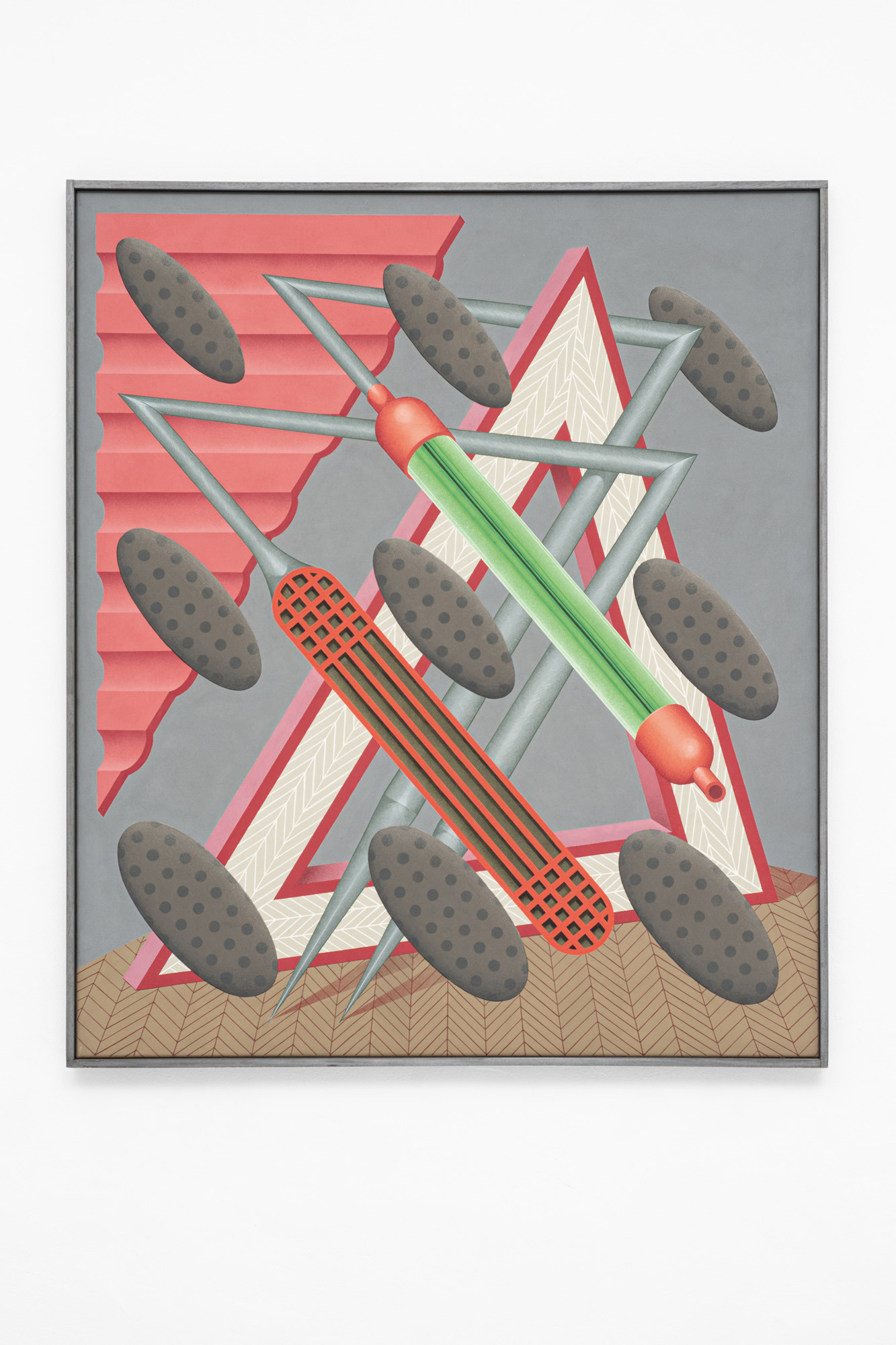

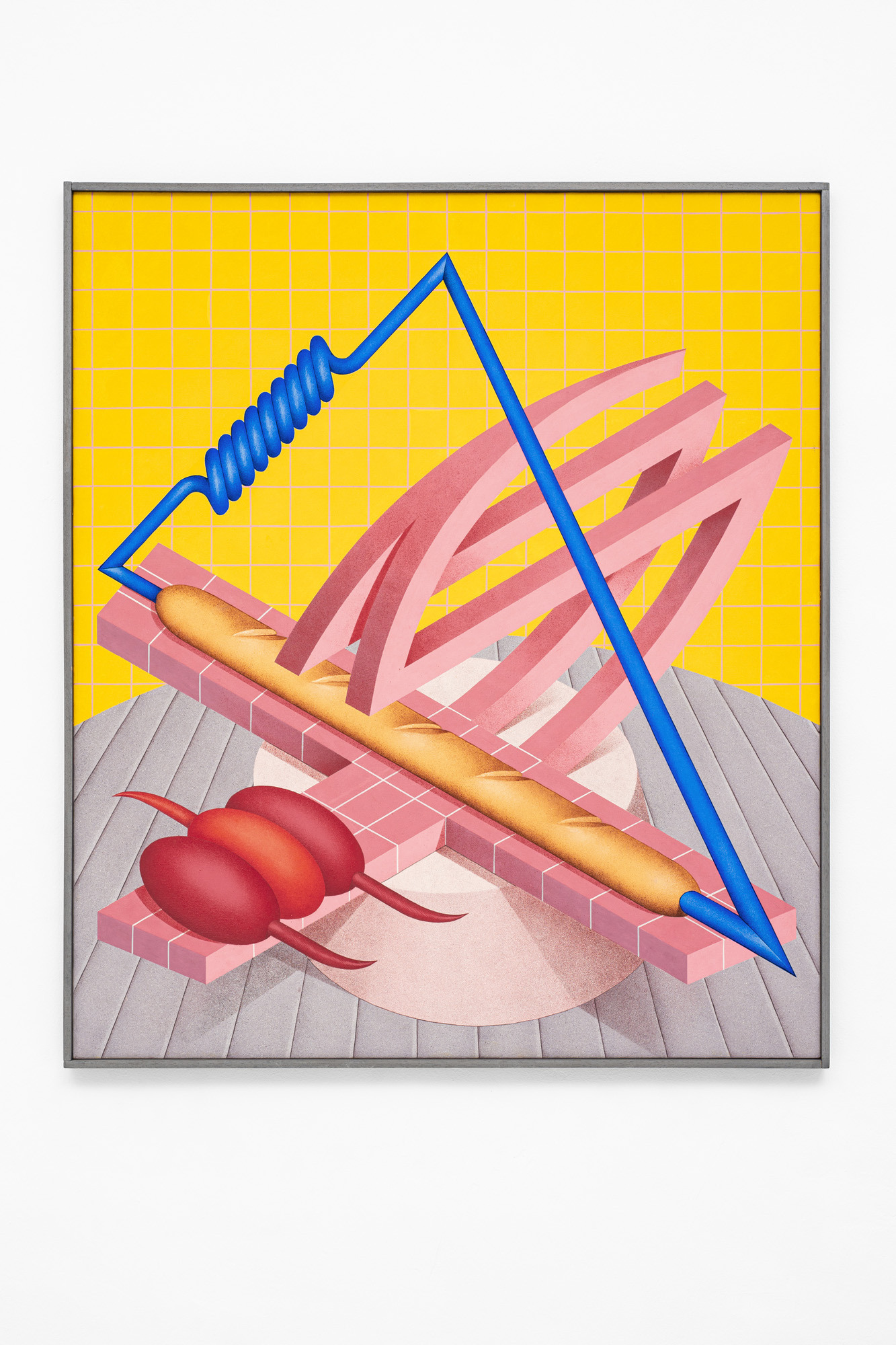

Konstruktion mit Dreieck, 1999, tempera on canvas, 110 x 95 cm

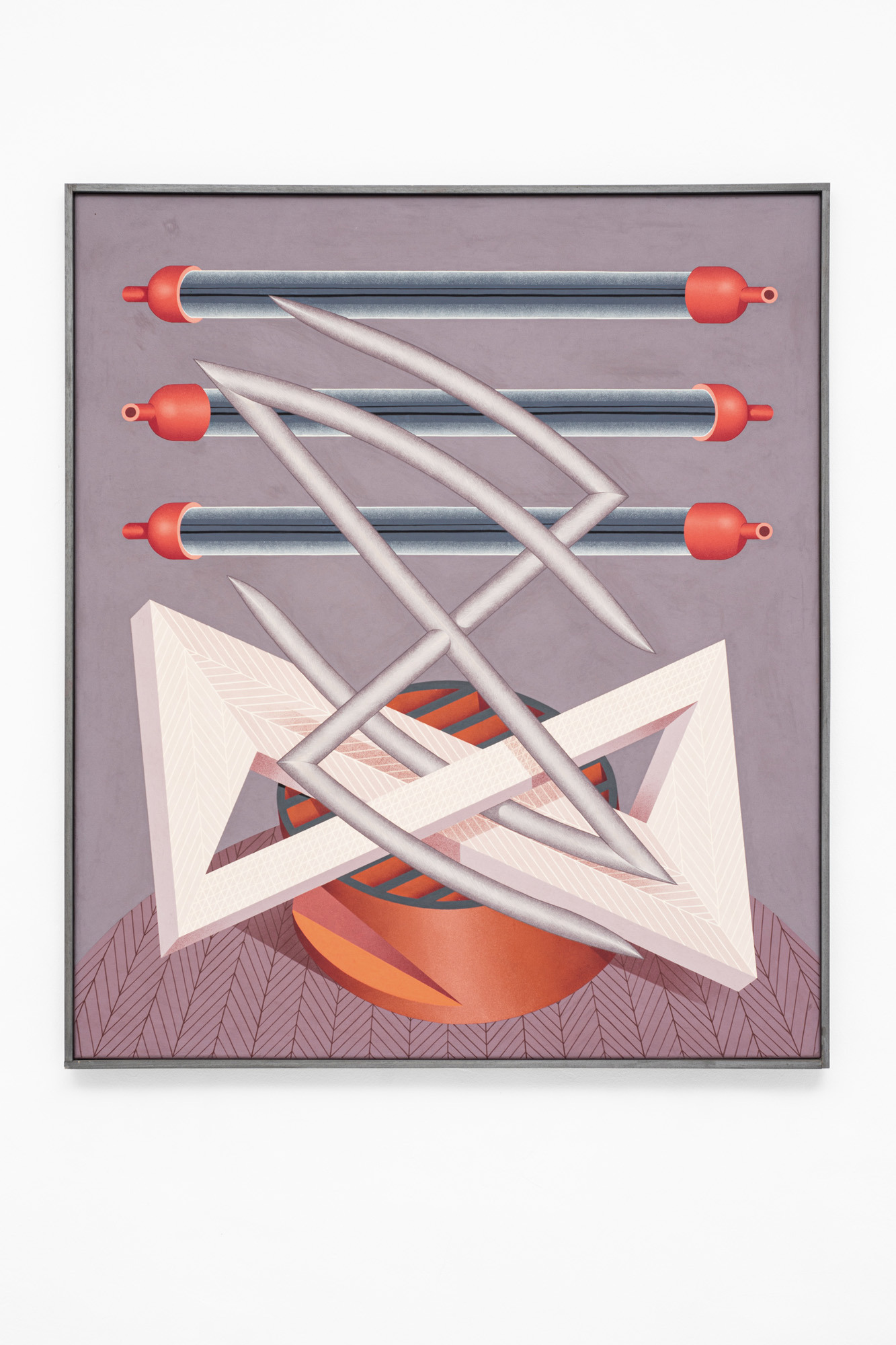

Konstruktion mit schwarzem Licht, 1999, tempera on canvas, 110 x 95 cm

Jobst Meyer: Konstruktionen der Neunziger, 2022. Installation view, EXILE Erfurt

Konstruktion auf Swastika, 1991, tempera on canvas, 75 x 65 cm

Jobst Meyer: Konstruktionen der Neunziger, 2022. Installation view, EXILE Erfurt

Konstruktion mit rotem Hakenmond, 1992, tempera on canvas, 200 x 175 cm

Konstruktion mit Brot und Klammer, 1994, tempera on canvas, 110 x 95 cm

EXILE is pleased to invite you to the inaugural exhibition of our new exhibition space in the German city of Erfurt, Thuringia on March 18, 2023 presenting a solo exhibition by German artist Jobst Meyer (1940-2017) entitled Konstruktionen der Neunziger. The exhibition focuses on works created by the artist during the eponymous decade that reflect upon the fundamental socio-political changes predominantly experienced in the East German states of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) as a result of German unification.

Bouquets of unpredictable implications

Still-life painting as an independent genre first flourished in the Netherlands during the early 1600s. Various fruits, vegetables as well as insects, dead game or precious items were painstakingly arranged on wooden table tops most commonly in front of dark, monochrome backgrounds. Immaculately executed and at first sight just formally decorative, these arranged objects represented more than what meets the eye. Each flower, fruit, vegetable, animal or object could hold an inscribed symbolic value beyond its painterly surface. Reflecting upon the growing autonomy of the bourgeois class, these paintings, themselves luxury objects, were commissioned to represent the social status and moral integrity of mercantile traders in an increasingly connected and urbanized society.

A common thread in the predominantly Dutch or Flemish floral still-life paintings is the assemblage of flowers from different countries or even continents in one vase and at one impossible moment of collective blooming. Still-life paintings became constructions of reality according to a client’s requests that communicated moral codes as well as social status through the painted arrangements of objects. Today, many of these specific meanings or codes are unknown to the majority of viewers, hence what might have appeared obvious to the elusive circles these paintings were originally aimed for is today left to specialized art-historical knowledge.

The 1990s, the decade in which Jobst Meyer painted the seven works exhibited in the exhibition, was characterized by substantial socio-political changes in East and West Germany. Following large scale protests in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the subsequent fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, both east and west German societies entered a complex process of transition. What seems as a historical given today, the German unification under a predominantly West- German capitalist system, was by no means certain in the early 1990s and even past unification further positive as well as negative social transformations impacted both parts of the newly unified Germany.

In his paintings, Meyer references technical as well as formal attributes of traditional still-life painting. On a technical level, Meyer exclusively worked with self-made, non-industrial tempera paints that he carefully layered on top of on another. On a formal level, Meyer’s works follow his predecessor’s three-fold compositional split into table-top, objects arranged upon and staged in front of an often plain, dark background. Meyer exchanges the predominantly natural objects with abstract forms ranging from crosses, hard-edged spikes, and moon-like shapes, to shapes that appear as if in stages of in-between. Physical objects appear in form of musical instrument-like trumpets or horns, wheel or ladder-like structures, or letters of the alphabet. Many of the more or less distinct shapes and objects in Meyer’s paintings seem to be caught in a kind of morphing, transitioning, intertwining or merging state from one form to another creating compositions that seem caught in an almost filmic state of flux just like an interim page of a flip book. These complex structures are placed upon textured plains quite similar to the table tops used in the paintings of his 17th century predecessors. The plain, usually dark and monochrome background’s is replaced in Meyer’s paintings with equally monochrome, yet often fiercely colorful, or in some cases wallpaper-like patterned, backgrounds.

On an interpretational level, Meyer’s painted compositions might also mean much more than what meets the eye at first glance. Especially when seen in context with the date of production, his paintings can appear as a graphic analysis of society in transition. Like the often impossible intersecting floral attributes of the 17th century, Meyer’s paintings invite the viewer to reflect on what these various symbols as well as their in-between stages can mean by themselves as well as within the overall formal composition. Is an electrified, bulb-like doubled flash, or a cross in its morphing distortion reminiscent of popularized right-wing insignia? If so, does Meyer interpret the troubling rise of neo-fascism in both parts of Germany as a consequence of German unification? Does Meyer, who also designed posters for some May 1st demonstrations and other left- wing political agendas, paint a rather dystopian view of the developments in 1990s Germany that critically questions the common narrative of the peacefully unified nation? Does Meyer’s pastel to vibrant color palette lure the viewer into visual consumerism that lays a cotton candy-esque diffusion over the greater societal challenges addressed in the works? Finally, are these works specific to 1990s social change in Germany or do they not have more universal questions embedded?

A particular link between Meyer’s work and the historical reference is the inclusion of loafs of bread in some of the works. While a rather basic food source not meant to elevate a patron’s status, it does find itself in many 17th century kitchen still-life paintings as symbolizing either the body of Christ, the simplicity of everyday life or a certain moral humility. In Meyer’s paintings, bread appears in form of a conventional baguette and is the only clearly defined and undistortedly painted object.

Meyer’s reasons for being so particular and specific are unknown and we can only interpret. Yet, the inclusion of bread, as a basic food for human existence and survival might be seen as an intentional hint by the artist towards a socio-political reading of the artworks. Potentially this loaf of bread can even function as the concrete link or access point for an analysis of the work in the tradition of still-life painting past a formal surface?

In difference to the historical predecessor, Jobst Meyer was not painting for a patron or client but acted as an autonomous artist whose overall social, political as well as creative personality is embedded in his works. Meyer’s painted constructions hold no elitist codes readable only by the select few, instead the artist uses shapes and forms that are universally open and accessible to all. Yet Meyer did not have a large audience for his work in later stages of life and so these paintings were, to this moment, not seen by many. With time having passed since their production in the 1990s a new reading of Meyer’s work is possible and the urgency to critically address, question, and reflect upon dangers to civil societies remains fundamentally important today. Meyer’s paintings, when exhibited in the city of Erfurt in 2023, invite the viewer to analyze and abstract from the paintings’ symbolism, to the local placement, to the particular time we live in.

Meyer’s works from the 1970s were previously exhibited at EXILE Vienna as part of the exhibition Monument Error in 2021. Parallel to this exhibition, EXILE Vienna hosts the second solo exhibition by Jobst Meyer’s partner Sine Hansen (1942-2009). The exhibition is entitled Spannungszangen and features paintings created during the 1970s. On view at EXILE Vienna until Apr 15.

Jobst Meyer (1940-2017) studied at Akademie der bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe (1960-63), and at Hochschule der Künste, Berlin (1963-68). From 1982- 2010 Meyer taught at the Hochschule für bildenden Künste, Braunschweig. In 1973, he received the Villa Romana award and residency in Florence, Italy. Meyer exhibited in numerous solo exhibitions, amongst them Galerie Junge Generation, Hamburg (1967); Forum Stadtpark, Graz (1969); Galerie Klang, Cologne (1973, 1974), Galerie Thomas Wagner, Berlin (1975), Galerie Niepel, Düsseldorf (1981, 1991) and Landesmuseum Oldenburg (1998). Selected group exhibitions include Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (1966), Kunsthalle Recklinghausen (1967, 1969), Kunsthalle Nürnberg (1968), Kunstverein Salzburg (1970), Haus der Kunst, Munich (1970), Akademie der Künste, Berlin (1973), Kunsthalle Kiel (1977), Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (1982), Ludwig Forum, Aachen (1992), and Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr (2016). Amongst others, his work is in the public collections of Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Berlinische Galerie, Rheinisches Landesmuseum, and Bundeskunstsammlung, Germany.

Christian Siekmeier