Duncan Poulton and Nick Smith

Duncan Poulton: Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow

Project Info

- 💙 Division of Labour, Salford

- 💚 Nathaniel Pitt

- 🖤 Duncan Poulton and Nick Smith

- 💜 Natalie D Kane

- 💛 Rob Battersby

Share on

Duncan Poulton 'Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow' install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Advertisement

Duncan Poulton 'Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow' install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton 'Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow' install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

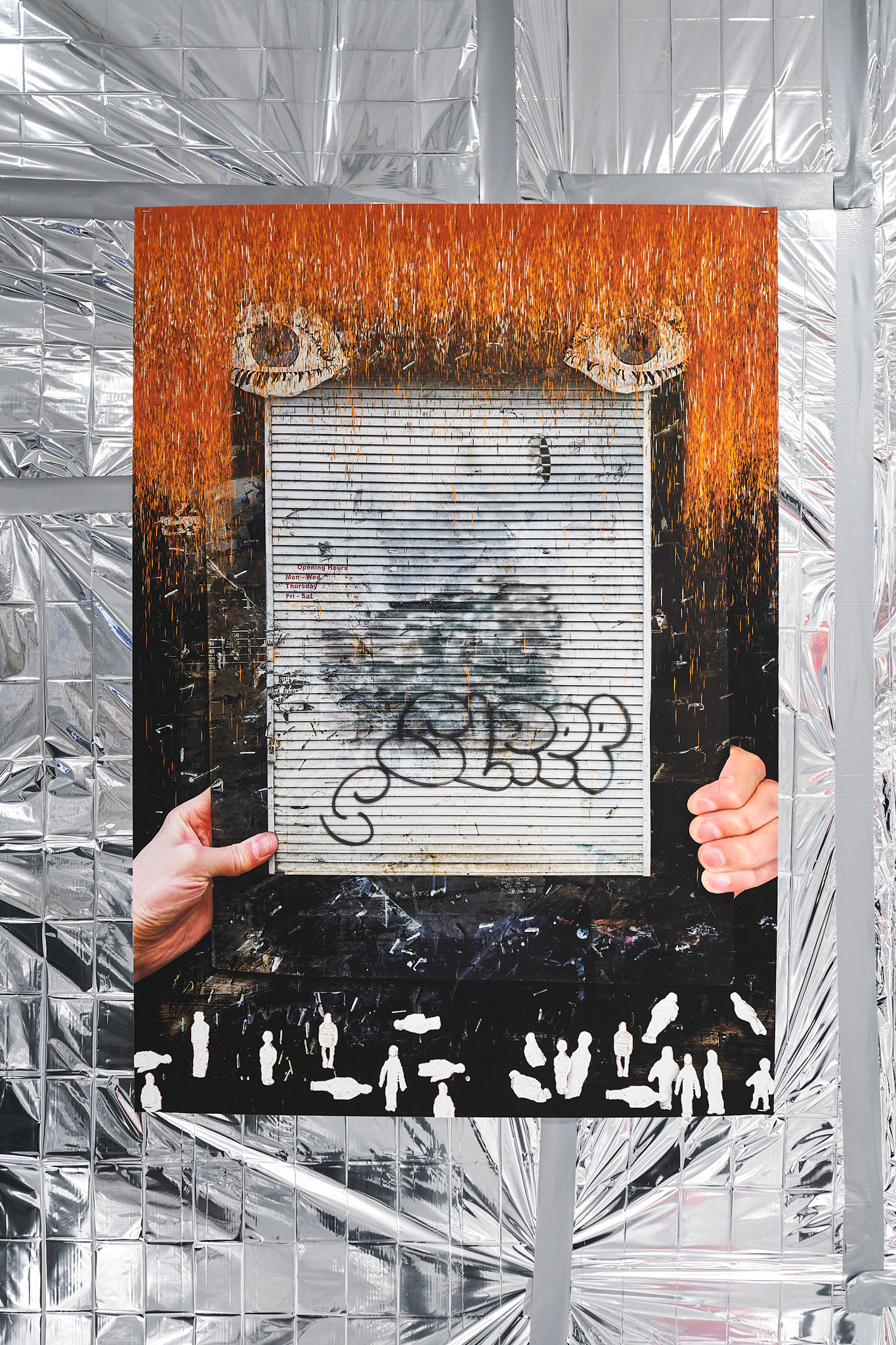

Duncan Poulton, 'Sleep Today' (2023), digital collage print on archival paper. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

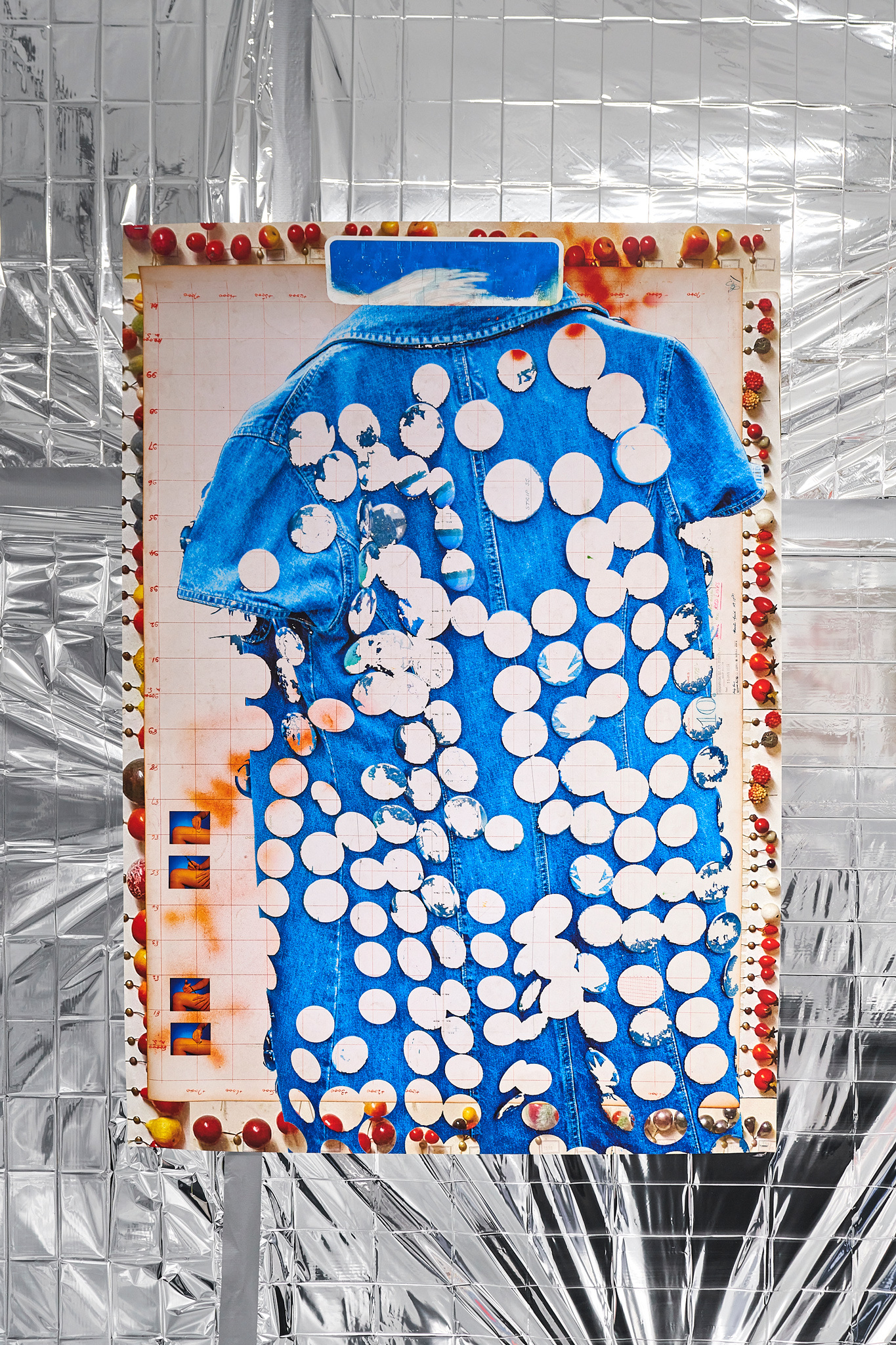

Duncan Poulton, 'What's the point of getting old?' (2023), digital collage print on archival paper. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton 'Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow' install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton, 'We were here but now its time to go' (2022), digital collage print on canvas. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton & Nick Smith, 'Y2K' (2023), single-channel digital video. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton & Nick Smith, 'Y2K' (2023), single-channel digital video. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton, 'Splendid Trading' (2023), digital collage print on archival paper. Install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

Duncan Poulton 'Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow' install view at Division of Labour, Salford, 2023. Photo by Rob Battersby

The gallery is lined in aluminium foil, transforming it into an enclosure known as a Faraday Cage, designed to shield us from phone, wifi and other electromagnetic signals. It is an experiment in freezing the audience in time, suspending our animation while we try to realign ourselves with the many possibilities that the Millennium threw at us.

In the first half of Duncan Poulton and Nick Smith’s film ‘Y2K’, as we re-live the build up to the Millennium, it’s hard not imagine how things might have been different. The world was hurtling towards global technological uncertainty, making bets on systems that had rapidly outgrown our comprehension. The computer was suddenly less of a sparkling innovation we’d learn about on technology entertainment shows like the BBC’s Tomorrow’s World (1965–2003), but had quickly become something to be feared.

In present times, we are drawn into a state of promise and technological fear, as we were 23 years ago, a symmetry pulled into focus by Poulton and Smith’s film. However in the anticipation of artificial intelligence there is no superbug or clock to set back time. We are in a constellation of moving speculative futures that present themselves as technological certainties. In 2019, as hype was building, a survey in a report by MMC Ventures found that two thirds of AI Startups had no ‘AI’ in them at all – the industry was willing a dream into being, an imaginary landscape for them to step into once the conditions were right. In this evolving speculation, imagining any collapse brought about by artificial intelligence sometimes feels less like a crash however, than a freefall. Where the year 2000 presented a singular unifying moment of destruction or salvation, we now find ourselves in much more diffuse, confusing and gradual circumstances – an underlying nervous hum of uncertainty.

As a society that has matured with technology, we are overwhelmed by the images that feed artificial intelligence technologies and the images that are produced by them, an Ouroboros of visual culture that makes it difficult to know when everything started. Poulton’s collages come as a result of a personal algorithm, a meticulous and eclectic process of collecting, a marriage of human and machinic methods. The works in this show introduce personal images from Poulton’s family photo albums from the years 1999 and 2000, obscured, redacted and melted in with found material created by others. We forget that in the archives of ImageNet – the wildly flawed image database released in 2009 by Dr FeiFei Li that trained so much of our neural networks – were personal photos too, because how else would a machine know what a family is supposed to look like? Within the archives of systems are unknown connections, but in Poulton’s case this constellation of unconscious information gathering creates a problem for any machine if it were to try and interpret it.

Poulton’s oscillation between the deeply personal and the completely arbitrary, his compression of time and meaning, are the exercise of an individual who is attempting to live within a world constantly renewed by images amid the ‘photographic surplus’, as he calls it. Poulton describes this process to me as ‘drifting’, comparing himself to a search engine wandering a sea of images which themselves have already been filtered through countless technical systems.

All images undergo manipulation as a result of their production, but we are so used to not knowing what is a computationally manipulated image, we no longer seem to care, or feel unable to. In the multi-layered construction of his collaged works, Poulton gives a clue to this sleight of hand, drawing attention to their artifice. We are mediated by images – to pull from Vilem Flusser on photography – we need images to make the world more comprehensible to us, more immediately accessible. It’s as if each of Poulton’s collages is a personal CAPTCHA, enabling him to learn about his psyche through what he consumes. They offer a way to gradually decode his reality among this visual noise, through an excavation and re-threading of the user-generated histories and long-forgotten uploads that litter cyberspace.

To me, ‘Imagine What We Can Do Tomorrow’ is an exhibition about anxiety, from the emergency blanket-lined walls to the ways in which Poulton tries to sift through the visual ephemera of a generation promised so much at the turn of the Millennium in his film with Smith. The show exposes our anxiety about the things we used to feel excited about (the future, being young, technology), the anxiety of what we’ve left behind in the wake of emerging technologies, and how we experience anxiety as a society through media and privately. The exhibition brings into view the emergency broadcast of information that is collectively felt at times such as the Millennium, both at the time of its arrival and the retrospective analysis we compact together through history. We don’t get to see or feel these moments unmediated, in parallel with everyone else’s; we don’t get to see the whole system working at once, it’s not designed that way. We only see it when it breaks.

Natalie D Kane