Jędrzej Bieńko

Human Decomposition

Project Info

- 💙 Pola Magnetyczne Gallery

- 💚 Patrick Komorowski

- 🖤 Jędrzej Bieńko

- 💜 Szymon Maliborski

- 💛 Bartosz Górka

Share on

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Advertisement

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Bird, Human and Bouquet of Flowers", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 200 x 160 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Two Birds and Eyes" (diptych), 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 170 x 260 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 150 x 180 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Portrait with a Flower", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 130 x 100 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Bird with a Human", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 170 x 200 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human with a Heart in the Hand", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 130 x 170 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Walking with a Human", 2023, acrylic on linen canvas, 170 x 140 cm, courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

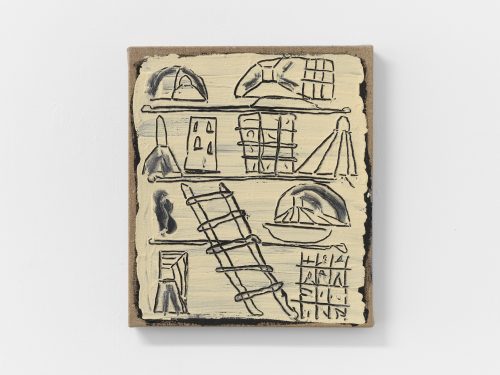

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Untitled", 2023, video, 03’27’’,courtesy of the artist and Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Jędrzej Bieńko, „Human Decomposition”, exhibition view, courtesy of Pola Magnetyczne Gallery, phot. B. Górka

Pola Magnetyczne Gallery is pleased to announce the first individual exhibition of Jędrzej Bieńko in the gallery entitled "Human Decomposition", where his latest paintings and a video installation will be presented.

"Walking with a Human" by Szymon Maliborski

Translated by: Marcin Wawrzyńczak

“Rawa, in a gray field a crowned virgin in a red dress, arms outstretched, riding a black bear” – thus Jan Długosz described the Rawicz coat-of-arms in the oldest surviving Polish heraldry book. A few centuries later, walks along the Bzura River became an inspiration for a composition that looks at the human-animal relationship in a completely different way. Niedźwiada – another name of the Rawicz coat-of-arms – a proud woman riding a predator, dismounted it, turning into a human figure led on a leash by a creature with melancholic eyes. This is how one could briefly describe the painting "Walking with a Human", one of Jędrzej Bieńko’s latest canvases, well reflecting the direction of his interests.

The artist’s works are a journey through a strange borderland that has absorbed something from heraldry, fanciful bestiaries, and old iconography of fauna and flora. In this landscape with blurred boundaries, man has become entangled as a figure that one can experiment with, as a body that is pierced by fangs, beaks, stems, and thorns. It is an element inscribed in the environment of changed relations, where not only have the old hierarchies exalting the human over the animal ceased to apply, but where the boundaries between individual subjects have also been blurred. This seems to be a characteristic feature of the artist’s current investigations – a state of intertwining, where one form can give rise to another, where flowers can grow from hands or eyes. This state of entanglement, of self-feeding, eating and being fed, would be a painterly response to the way we usually construct a difference between “animality” and humanity. In place of the strangeness that the animal embodies as something non-human, the artist strives to familiarize that which was alien and becomes familiar, part of one’s own body. This meeting sometimes has the character of piercing, literally entering the body. The beings caught in the process of penetrating each other are not obviously antagonistic, however. This is not a shockingly aggressive image of a clash between different species, but rather one that evokes a strange melancholy, a sense of mutual passivity, reconciliation and acceptance of one’s role. One can even assume that some kind of consent to human self-sacrifice is suggested here. The humanoid figures seem devoid of personality (not to mention genitals) and the creatures present on the canvases are strangely aware and acting intentionally. Is it the shame of man towards the animal, once described by Jacques Derrida in his essay, "The Animal That Therefore I Am?". Perhaps it is a world of a strange carnival characterized by a reversal of roles, a negation of the existing order, but without the ecstasy usually accompanying it.

The image of the body as soil for plant growth can, in the domestic context, evoke experiences of the horrors of war and mass graves blended into the landscape. In this case, however, it is a reference to other themes, more like a strange fairy tale where one thing can change into another, where flowers can inflict wounds, but also heal them. Not dead and not fully alive, but still staring at the viewer, the figures are in a state of melancholy, perhaps after losing their subjectivity, understood as integrity and separation from the world. However, this does not seem to be a traumatic experience, but rather a more capacious one, involving being in a relationship of strange metabolism. Consuming and being consumed in a cycle of dying and growing again.

A desire to cross hard boundaries is also evident in the choice of the painterly means employed by the artist. The unprimed canvas with a loose weave structure lets in a lot of light and exposes itself as the material on which the representation is created. It is constantly in dialogue with the airbrushed layer of paint while at the same time harmonizing with the intention of blurring the contours of things, washing away individual elements of the composition, isolating them in a fuzzy manner from the landscape loosely inspired by the artist’s native area. This double porosity of matter and representation makes it possible to meet rigid boundaries, to make them non-obvious in two ways. These paintings require long staring to notice all the forms constructed with a subtle change in colour saturation. The most strongly emphasized motif, which is often a flower twisting around the image, blurs in the rest of the background, anchoring in it as if in a layer of earth.

Standing in front of Bieńko’s painting, one feels also like confronting a fabric, a woven composition that may resemble strongly faded tapestries. Their specific “patina,” a result of their materiality, is also achieved by working with an airbrush, a tool that is modern by the standards of painting. Some of the creatures appearing on the canvases could find their predecessors in the series of Wawel Castle tapestries devoted to animal and landscape themes. Reflecting the Renaissance man’s interest in the surrounding nature, these tapestries constitute a special quintessence of humanism, which is currently being rewritten through new critical filters.

Through the materiality of raw linen shines also in these works a fascination with religious iconography and the motifs of suffering associated with it, which in Catholic culture is endowed with numerous positive meanings. I think, however, that they are not about reconstructing meanings, about interpreting their different elements as symbols having their semantics in the Christian imagination. It is rather making use of these motifs, but at the same time embedding them in a different universe, devoid of personal transcendence. Also in a world where the phrase “subdue the earth” does not apply.

The composition "Pelican Feeding the Young" could indicate a reworking of Christological themes. Here, a pelican tears its own breast apart with its beak, feeding its two chicks with the blood flowing out. For centuries, this image has functioned as a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. Unlike in traditional theology, however, I would not expect this sacrifice to be a symbol of the redemption of sins. This would be an iconographic answer to an old philosophical question that Derrida also pondered; a question about the ability of animals to suffer and their ability to sacrifice themselves, empathy beyond the limits of human-centred logos. If it is a sacrifice, it is one offered to nature, an atonement for sin against another creature, rather than the salvation of mankind.

What is particularly suggestive in the latest instalment of Bieńko’s work is the relationship between the wound and the flower, the puncture of the body and the opportunity for something new to gush out of it. A flower that grows from a wound, a flower that accompanies a wound, and finally a flower that is new life on a strange non-dead non-living body. Stigmata, a token of being chosen, imitation of Christ’s wounds, a kind of compassio (compassion), used to be a similarly nonspecific affliction. These bloody marks did not heal, but they did not fester either. According to accounts, they smelled of flowers, e.g. roses, plants associated with the Passion. It is impossible to unequivocally decide exactly what happens in Bieńko’s linen-support compositions; whether it is a case of parasitism, of a plant taking control of a zombie body, or a disturbing symbiosis, the meaning of which is fulfilled in a spiritual but also non-religious sacrifice. Perhaps, as in the case of the stigmata recognized by the Church, suffering is not senseless, but leads in a completely different direction, being the price to be paid for a new, not exclusively human, reality. Fortunately for the works, these serious dilemmas are often evoked by slightly grotesque, mannered, and highly stylized forms. They are set in a dreamlike landscape where sfumato blurs the sharp contours of things. Consequently, we can smoothly move our eyes from one form to another, following the artist’s intention, walking with a human, perhaps without a clear purpose.

Jędrzej Bieńko – born in 2000 in Warsaw. He’s currently studying at the painting department of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, in the painting studio of prof. Wojciech Zubala.

Szymon Maliborski