Simon Petepiece

Four Quarter Round

Project Info

- 💙 Espace Maurice

- 💚 Marie Ségolène C Brault

- 🖤 Simon Petepiece

- 💜 Emma Pope

- 💛 Manoushka Larouche

Share on

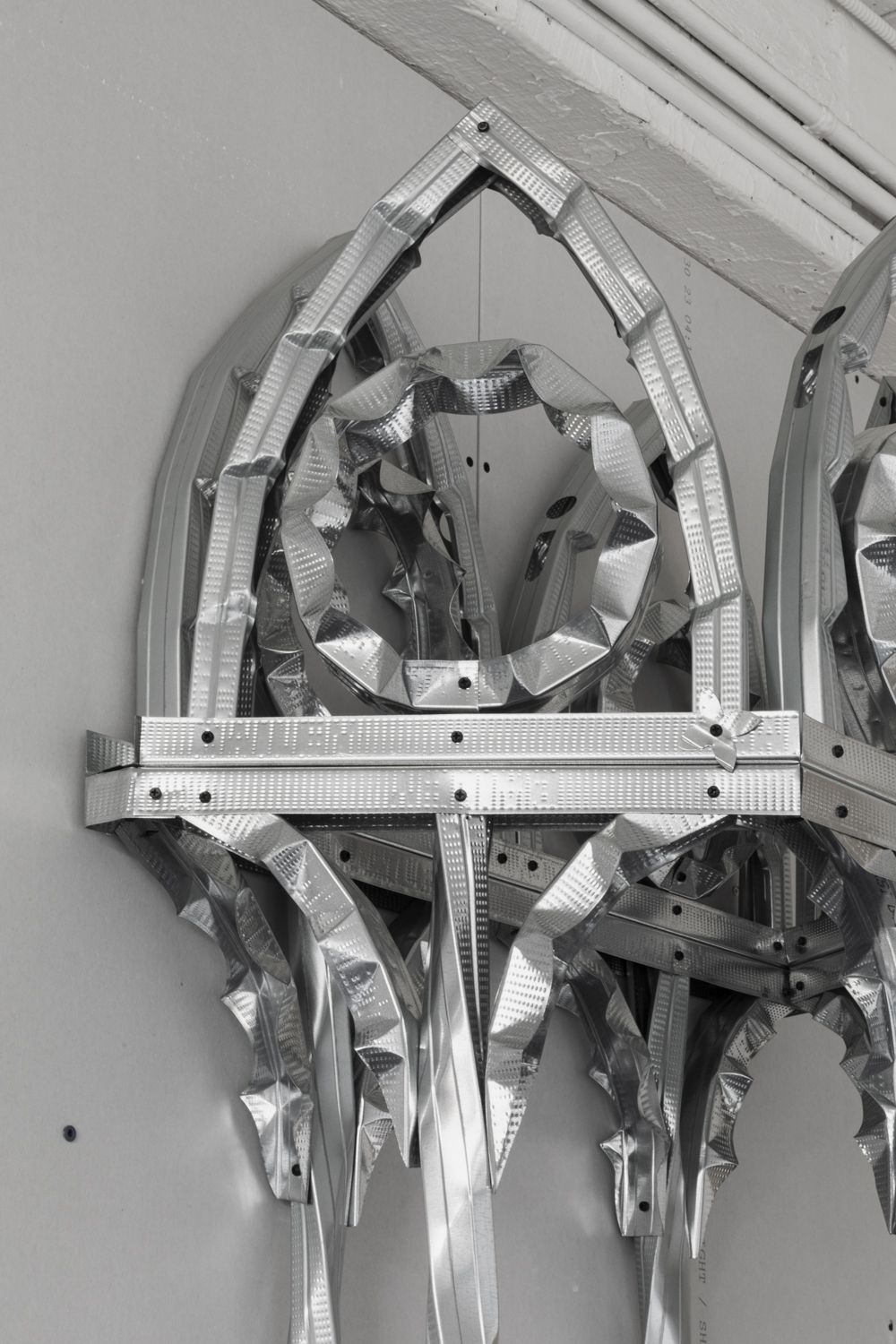

Bay Window (2023), Metal Studs, 36x60x16 in

Advertisement

Gallery view, Bay Window (2023) and The Raft (2023).

The Raft (2023), Primer, Joint Compound, Drywall, 10x10 in

Gallery view: Spike (2023), The Raft (2023), Down the Path (2023) and Rose (2023)

Spike (2023), Metal Studs, 32x32x120 in

Spike (2023) Interior view

Spike (2023) Detail

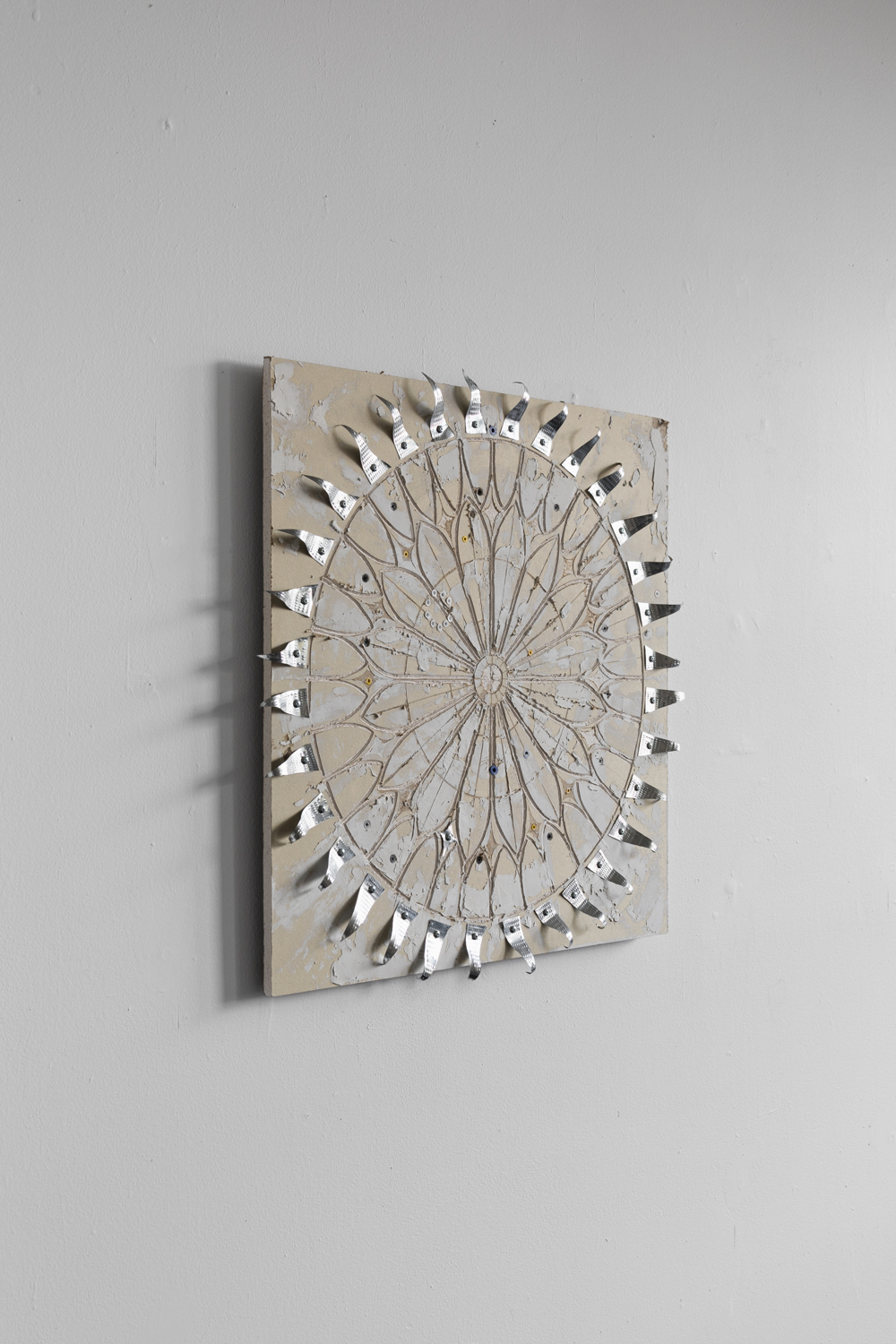

Rose (2023) Primer, Joint Compound, Drywall Anchors, Metal Studs, Drywall, 24x24 in

Rose (2023) Angle view

Rose (2023) Detail

Rose (2023) Primer, Joint Compound, Drywall Anchors, Metal Studs, Drywall, 24x24 in

Down The Path (2023) Primer, Joint Compound, Drywall Anchors, Metal Studs, Drywall 10x10 po

Down The Path (2023) Angle view

Down The Path (2023) Detail

Down The Path (2023) Angle view

Down The Path (2023) Angle view

Bay Window (2023) Detail

Rose (2023) Detail

Four Quarter Round

Simon Petepiece

Espace Maurice

Whoever sings, is said to pray twice.

The French-born composer, likely known as Léo prior to ordinance, was the architect of sacred polyphony in the high Medieval era. Magister Léonin (fl. ~1135-1201) wrote polyphony into the sacred sphere, producing codices with nearly 500 extant liturgical settings in the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris throughout the years of 1163-1190. Its style was of the aptly-named organ (organum, organi; pl. organa). Léonin’s organ was two-voiced, but the gradual development of Gothic polyphonic technique by the innovations of his ambitious begotten pupil Pérotin resulted in three- and four-voice dominance, parallel with the architectural traction of tre- and quatrefoil rosettes in this organ’s “body.” Indeed, the Trinitarian doctrine itself sees its origins in these Gothic proportions: by the 13th century the numerological trinity and quaternity would be housed within triple nave basilicas.

Naturally, the mutual relationship between a structure’s anatomical form and its resultant acoustic characteristics has identified itself: both are inherent in the material and spiritual fold of religious ritual. Micro-ornamentation on the macro-scale is imminent through windows, steeples and spires which diffracted the voices reading similarly-adorned stacks of vellum manuscripts. Within the Gothic period of high Medievalism, spaces of worship thus served as a clerical body complete with organs—resonant pipes of metal and those of flesh—which fulfilled the transport of sacred oration in desired exitus-reditus through musical organa.

There is a psychic structure within proportional and geometric operations which mathematicians call the “ordinal,” sharing its name with the prescribed liturgical book for rites and prayers of ordination and consecration to the Holy Orders. In Medieval liturgies, ordinals supplied instruction on how to use the other various books necessary to celebrate the liturgy and added rubrical direction to the recitation of the Mass. In these halls, it was necessary to create an atmosphere of exaggerated solemnity and even a certain fear of the Creator’s greatness in reverence. Visual arrangements of frequency and rhythm—articulated through bas-reliefs, windows and pillars/buttresses—fulfilled sacred, social, aesthetic and sonically-functional organization.

*******

A high Gothic cathedral’s towers, belfries, steeples and spires point upwards. There are multi-colored reflections of stained glass telling the story of the Gospel. Its intricate architecture is the frozen music. It is characterized by vertical proportions, windows of tre- or quatre-foiled make, pointed arches and external support through buttressing.

Through these ornate windows, the execution of the Divine Office begins at 3 a.m. with a Matins office of the quotidian Mass Ordinary. At a cantor or cantrix’s signal, the very first words of the monastic day are orated from one side of the oratory as versicle:

Domine labia mea aperies

Oh Lord, open thou my lips

Once the phrase’s diffractions have sufficiently sprung across the intricate Gothic architecture, a response emits from the cathedral’s opposite side:

et os meum adnuntiabit laudem tuam

and my mouth shall show forth thy praise

After, the cloister resigns to respective chambers for study. Memorization is practiced in a rosary-like fashion of mnemonic arithmetic. Lectio divina or “sacred reading” ensues with the recitation and repetition of each verse, to facilitate contemplation of various interpretations. It is a form of prayer that has often been compared to a cow chewing its cud in ritual rumination.

As the crepuscular hour closes at around 5 a.m., the cloister returns to the oratory to sing the office of Lauds. Their focus remains on the cantor or cantrix as they chant the invitatory lines of the office, a verse from Psalm 69:

Deus in adiutorium meum intende

O God, make speed to save me

Domine ad adjuvandum me festina

O Lord, make haste to help me

*******

The first practitioners of sacred polyphony sang a proportional music which involved a sense of time and a capacity for memorization, as well as a signature “unaffectedness” in its deliverance unto the divine Creator, that is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to imagine outside of such a context.

This liturgical sound – traditionally referred to as plainchant, considered the “physical core” of the liturgical word – was rife with a fascination of numerological concern. Its fixation upon proportions and ratios is exemplified through symbols, or “ligatures,” which signified specific mensural groupings of musical notes relative to each other. Rhythm was certainly complex as it is notoriously difficult to translate into modern Western notation due to the intricate implementation of relational devices such as hocketing, polyrhythm and polymeter. In the vertical domain, proportionality of pitch was similarly exhibited with tuning or “dividing” of the octave; the Pythagorean comma being used early to denote a fifth. A chant melody would be harmonized by the same melody or its transposition by consonant interval as the organum, and a lower (tenore) line would be held or stacked. These voices would alternately merge into a single melody through parallel stacking. This early implementation of heterophonic polyphony implements a Medieval harmonic-cadential language highly idiomatic to its time, based on transposition through the operations of three simple and three compound intervals: fourths, fifths, and octaves; octave-plus-fourths, octave-plus-fifths, and double octaves. These fractions also happen to coincide with resultant partials’ intervals found in the harmonic series.

A large, ornamented tome full of these glyphs and sigils would be encircled by gathering decryptors, the cloistered worshippers fulfilling the Hours. The cloister, orating the music, weren’t looking at what they were singing, but instead fixating heavenwards. The large tome was to remain before the worshippers so as to ensure obedience unto the holy scripture of the Mass, as well as the complex systems of ligatures which illuminated its delivery. However, a certain meticulousness was to remain intact with this fixation for memorization which proscribed worshippers to rely upon sight-reading its content. Thus we may see the unique problem which plagued the liturgical worship-performance of this time: that of where the eyes must lie. From the worshippers’ azimuth, intricate belfries drew the eye to the heavens—torn open between the flying buttresses and across the decadent clerestories—to beckon the sacred.

༓

Suggested further reading is found largely within contemporary writings of an English student by the name Anonymous IV ca. 1275 which divulges information on Paris organa. The Magnus Liber Organi by Léonin, specifically a well-known Viderunt Omnes Gradual setting for the Mass (which was expanded upon with Pérotin’s four-voiced organum quadruplum Viderunt Omnes), is widely available in recordings. However musical influence on the formation of Gothic Catholic architecture is to be found in the liturgical oeuvres of Léonin, however also by Robert De Sabilon, Pierre De La Croix, Pérotin, John De Garland, and Franco De Cologne; the nascent of sacred polyphony’s spearheading by the nuns of the parallel tradition occurring in the St. Benedict convent in Germany headed by St. Hildegard of Bingen is particularly of note.

Emma Pope