Isabella Fürnkäs

Inner workings: Das fressende Zimmer

Installation view | ›The Memory house‹ | print on silk cloth, metal structure | 200 x 200 x 150 cm | 2023

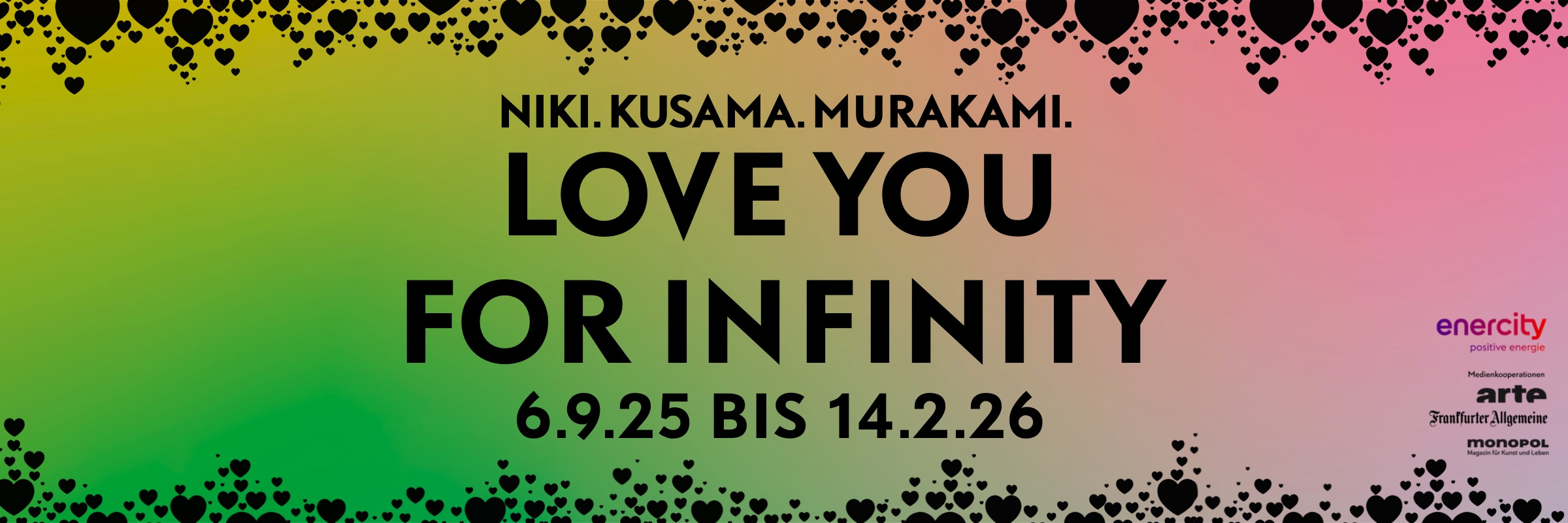

Advertisement

Installation view | ›Wer kontrolliert wen?‹ | ceramic plast, glass, tofu, lentils, pills, mirrors, marbles | size variable | 2023

Installation view | ›Mini Vagina‹ | Pencil on paper, plexi glass, cushion | 3,5 x 5,5 cm | 10 x 10 cm (framed) | 2023 | ›Untitled‹ | Japanese Ink on paper | 88 x 54 cm (framed) | 2023

Installation view

Installation view

›Mnemonic‹ | Print on PVC | 190 x 240 cm | 2021

Installation view | ›The laundry room‹ | 47 drawings of ›Laundry‹ | red yarn, paper clips, Ink on paper| 30 x 42 cm| 2023

Although the individual drawings, photos, films and installations by Isabella Fürnkäs are singular works with their own titles, they only unfold their full effect in their entirety. They are fictions and yet they are based in real life and thus they complement and reinforce each other. This is why the artist has grouped the individual works under the common title Inner workings, with the subtitle Das fressende Zimmer. With this title alone, she contrasts today's cult of the flawless exterior of bodies and objects with the uncovering and exposure of what is throbbing, flowing, being digested, moldering, decaying and ageing beneath the surface.

For example the small house that is set up in the entrance room of the Clages Gallery. The walls are formed by a transparent tights fabric printed with an abundance of photos, which gives the house a physicality. The fabric alone and especially the flood of images are uncanny. The pictures show decapitated queens, human entrails, pornographic scenes and witches... They are traumatic images from the cultural memory reservoir of the most diverse cultural epochs. They attract

the eye, they fascinate and they repel. Disturbed by the images, one hardly dares to look inside the house. And indeed; rumpled sheets, disorder... What has happened here?

Something similar happens when looking at the small drawings Mini Vagina, which is framed in a plexiglass block. It actually shows the vagina in detail. And although the drawing is very small, it has an intensity that virtually sucks the eye in. This intensity is heightened by the fact that the drawing is mounted very low on the wall, so that if you really want to look at it, you are forced either to bend forward or even to kneel. But already one averts one's gaze. You feel caught. But at what? Even the brief glimpse is enough to make us witnesses, more than that; it makes us enter the moist cave of the vagina as before the uncanny happenings in the house. And that is precisely what distinguishes Fürnkäs' works: They are staged in such a way that we become participants in an extremely intimate event and thus somehow complicit.

With this approach, Fürnkäs joins the ranks of such artists as the Vietnamese artist Danh Vo or the Georgian artist Tolia Astakhisvili. But unlike them, there is another level to her work: the comic. In the clutter of the house lie a computer modelled out of clay. In the other rooms, mobile phones, also unskilfully modelled out of clay, are piled up in cupboards and drawers. Their clumsy, material-heavy, archaic appearance is in stark contrast to the elegant electronic devices with perfect surfaces, such as those made by Apple. This makes them look ridiculous. And suddenly, thanks to this awkwardness and ridiculousness of the clay devices, a sense of the enormity, the recklessness, with which we outsource our own inner life,

our most intimate longings, dreams and desires from our own unpredictable bodies, susceptible to disturbances and injuries, to the mechanically controlled inner life of the lifeless computer.

And the installation Convenience, made from a shabby old fridge with a film running inside, also bears witness to comedy. It shows running female legs. The shot has something voyeuristic, slightly disturbing, especially since it is turned upside down. Here, too, one look is enough to make one an accomplice. And the towers, made of Japanese chewing gum cans, are also comedic. And then there are the many drawings hanging like laundry on linen. Over and over again they show the loops of the human intestine, this inner organ wrapped in disgust because of its digestive and excretory function. Even these drawings, staged in this way, are not without a certain comedy.

Despite the feeling of being involved in something threateningly mysterious, all these productions also provoke smiles that can turn into laughter. Laughter creates distance. And it is this distance that, in the face of the daily complicity that Fürnkäs' productions so skilfully recreate, enables us to digest the flood of fascinatingly repulsive images we see and possibly also to excrete them. And it is this ability that prevents us from going mad, that distinguishes the human body from electronic devices.

Noemi Smolik