Laurentius Sauer & Timur Lukas

ALTE NEUE SONNE

Project Info

- 💙 Nina Mielcarczyk, Leipzig

- 🖤 Laurentius Sauer & Timur Lukas

- 💜 Fredi Thiele

- 💛 Marco Dirr

Share on

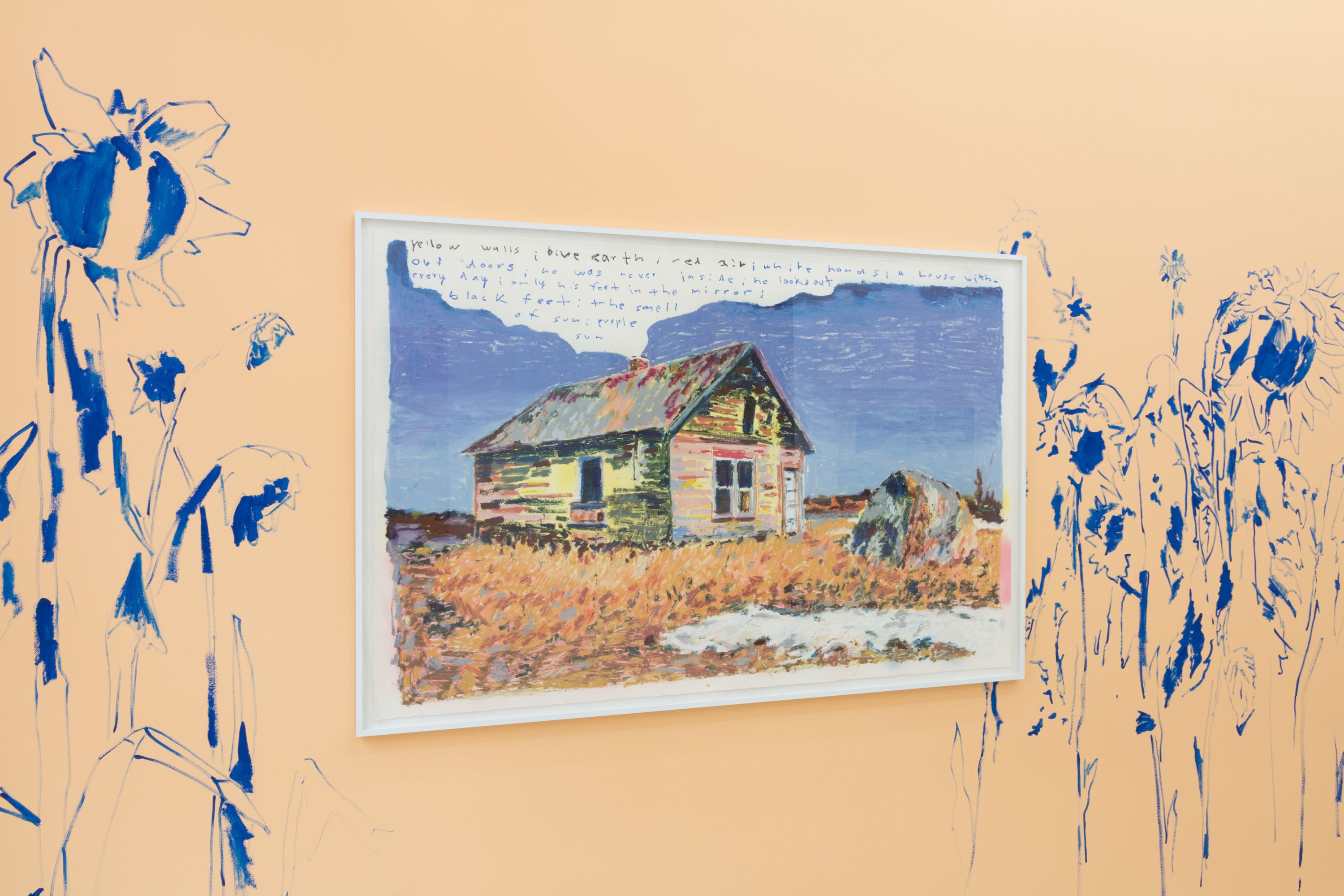

Installation view: ALTE NEUE SONNE, Nina Mielcarczyk, Leipzig 2024

Advertisement

Laurentius Sauer, yellow house purple sun, 2023 Öl Stift auf Papier, gerahmt 167 x 108 cm

Installation view: ALTE NEUE SONNE, Nina Mielcarczyk, Leipzig 2024

Timur Lukas Red sun, 2023 Öl auf Leinwand 180 x 140 cm, Stahlrahmen

Laurentius Sauer & Timur Lukas Due Two Paravent 1, 2023 Öl Stift, Lack auf Holz 194,5 x 250 x 60 cm

Detail: Laurentius Sauer & Timur Lukas Due Two Paravent 1, 2023

Detail: Laurentius Sauer & Timur Lukas Due Two Paravent 1, 2023

Timur Lukas Surrounding, 2023 Öl auf Leinwand 120 x 90 cm

Laurentius Sauer, waiting in a yellow car, 2023 Öl Stift auf Papier, gerahmt 101 x 65 cm

Laurentius Sauer, horses run at night, 2023 Öl Stift auf Papier, gerahmt 167x108 cm

Timur Lukas yellow light, 2023 Öl auf Leinwand 120 x 90 cm

Die Galerie Nina Mielcarczyk präsentiert in der Ausstellung Alte neue Sonne die Werke der Künstler Laurentius Sauer und Timur Lukas, die nicht nur eine enge Freundschaft und das Atelier teilen, sondern auch eine gemeinsame Spur des Romantischen in ihren Arbeiten hinterlassen. Diese romantische Einflussnahme erstreckt sich von den Sujets der Bilder (es sind die Vasen, Blumenbouquets und träumerischen Vistas) über ihre stilistischen Einflüsse bis hin zu den von ihnen gemeinsam hergestellten Ölstiften — es ist ganz hinreißend. Doch etwas stimmt nicht. Unter der ästhetischen Geborgenheit und Stille bewegt sich etwas.

„Kann man ein Sujet totmalen?“ — Timur Lukas

Es beginnt bei dem Paravent, der als zentraler Bestandteil den Raum der Ausstellung formt. So gewinnen ihre, teils zeichnerischen Ansätze (besonders bei Sauer) eine zusätzliche skulpturale Ebene, als Bild im Raum. Die entstehende „falsche“ Perspektive lädt uns ein die beiden Seiten näher zu betrachten und der Sache auf den

Grund zu gehen: Die einst prächtig dargestellten Sonnenblumenfelder sind öde und vertrocknet, die erst heimelig anmutende Hütte, entpuppt sich auf den zweiten Blick im Verfall.

Der Verfall, als Bedingung des Wachstums, durchdringt sowohl Sauers, wie Lukas’ Werk und schafft so die zugrundeliegende Brechung der sonstigen Virtuosität. Verlorengemeintes, Übriggebliebenes, noch-nicht-zu-Ruinen-Gewordenes speist die Motive ihrer Arbeiten und erklärt auch den gemeinsamen Fokus auf Architektur. Sie sehen Überreste eines bereits abgestorbenen Apparats, wie zum Beispiel die Villa im passend betitelten Werk „classic view“ von Lukas, die

von der kürzlich abgerissenen Villa von Harald Juhnke inspiriert ist. Lukas kommentiert dies kurz im Vorgespräch: „Wenig bleibt

übrig, bald ist alles verschwunden.“

Dieser Ansatz spiegelt sich in Lukas Recherchemethode, für die

er in Massen fremde Familienarchive aufkauft und nach Motiven durch- sucht. Ihn interessieren dabei die genaue Komposition alter Foto- grafien, wie sie sich wiederholen und wie sich innige Verbindungen zu diesen Fremden aufbauen lassen, wenn er durch ihre Leben blättert.

Historische Einflüsse finden sich auch bei Sauer, jedoch betrachtet er sie kritischer. Verlassene Scheunen, Pferde (die Cowboys sind bestimmt nicht weit), Gockel, abgedeckte Maschinen — alles alte Symbole männlicher Hoheit. Diese werden ergänzt durch kurze Textfragmente, die in ihrer Verbindung fragen: Wie aktuell sind diese Symbole noch und, viel wichtiger, was hat sie abgelöst?

Es ist zu beobachten, dass Sauer die Symbole unseres Zusammen- lebens untersucht, während es Lukas um ihre Darstellung geht —

die Art und Weise, wie sie abgebildet wurden/werden. Warum ist es immer die Blumenvase am Fenster? Was ist das intrinsisch anziehende in den alten Hoheitsdarstellungen? Warum sterben manche Sujets

nie aus? Lukas und Sauer verweisen in Alte neue Sonne darauf, dass die Antwort sehr viel düsterer ist, als vielleicht angenommen.

–

Galerie Nina Mielcarczyk presents the works of artists Laurentius Sauer and Timur Lukas, who not only share a close friendship and

a studio space, but also leave a common trace of romanticism in their work. This romantic influence extends from the subjects of the paintings (it’s the vases, floral bouquets and dreamy vistas) to their stylistic influences and the oil pastels they produce together—it’s quite adorable. But something is wrong. Beneath the aesthetic tranquillity and calm, something is moving.

“Can you paint a subject to death?” — Timur Lukas

It starts with the folding screen that shapes the space of the exhibition as its central component. In this way, their partly

graphic approaches (especially Sauer’s) gain an additional sculptural level, as an image in space. The resulting “false” perspective invites us to take a closer look at the two sides and get to the heart of the matter: The once magnificently depicted fields of sunflowers are barren and dried up, the hut, which at first seems homely, turns out to be in decay at second glance.

Decay, as the condition of growth, permeates both Sauer and Lukas’ work and thus creates the underlying disruption of the prevailing virtuosity. The lost, the left-over, the not-yet-ruined feeds the motifs of their works and also explains their shared focus on architecture. They see remnants of an apparatus that has already died, such as the villa in Lukas’ aptly titled work “classic view”, which is inspired by Harald Juhnke’s recently demolished villa. Lukas comments on this briefly in the preliminary talk:

“Little remains, soon everything will be gone.”

This approach is reflected in his research method, for which

he buys up masses of other people’s family archives and searches for motifs. He is interested in the precise composition of old photographs, how they repeat themselves and how intimate connec- tions can be established with these strangers as he flicks through their lives.

Historical influences can also be found in Sauer’s work, although he views them more critically. Abandoned barns, horses (the cowboys can’t be far), roosters, sheathed machines—all old symbols of male sovereignty. These are supplemented by short fragments of text which, in their combination, ask: How current are these symbols still and, more importantly, what has replaced them?

It can be observed that Sauer examines the symbols of our communal life, while Luke is concerned with their representation— the way in which they were/are depicted. Why is it always the

vase of flowers by the window? What is the intrinsic attraction in the old representations of male hegemony? Why do some subjects

never die out? In Old New Sun, Lukas and Sauer point out that the

answer is much darker than we may think.

Fredi Thiele