Robert Roest

Robert Roest at EUROPA

Advertisement

Eight Paintings Proving Angels Are Really Watching Over Us

For Robert Roest, the act through which sensory information is reproduced, imitated, and transfigured into thought, speech, dreams, images, film, art, writing, and so forth is a evolutionary survival tactic–it creates meaning.This process is so omnipresent and natural that, at times, it might feel that mimicked objects surround us more than anything. Plato would argue that these reproductions of nature force us further and further away from their original source material but Roest believes this interpretative process allows us not only to be conscious but self-conscious, even meta-conscious. Our mimetic acts are the way in which reality catches a glimpse of itself.

Eight Paintings Proving Angels Are Really Watching Over Us is a modified found title lifted from a viral listicle that collected and documented the choice moments in which clouds form uncanny resemblances of angels. The article and its title fascinated Roest: the implied challenge, the mental leap it asks of the reader: cloud, photo, angel, and proof of it even!

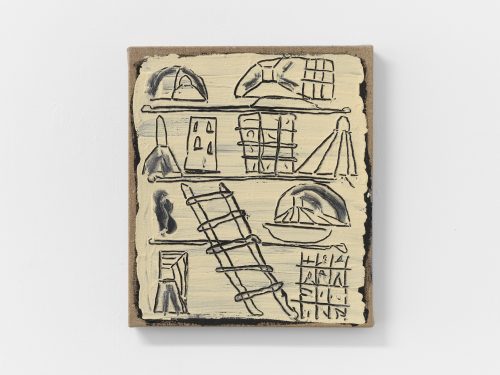

After graduating from the Utrecht School of the Arts in the Netherlands, Roest began to work in focused sets of five to ten paintings, most often investigating a specific theme, premise, or concept in an almost clinical fashion. This latest series–-the angel paintings–investigates the relationship between representation and deception by pushing the potential of artifice to its nth degree. Even the frames are an apt example of illusion: the weathered structures are meticulously rendered trompe l'oeil of actual frames. They invoke time as sunbleached snapshots of the sublime. The eroded, peeling paint of the frames work in sharp contrast with the traditional, pastoral landscapes below while a shining angel is crisply rendered above. Yet what is this angel but the most timeless, ineffable and complex system of all–weather, and specifically crepuscular rays, an effect that occurs when the contrast between light and dark is most evident. Humans have interpreted spiritual images in the sky since the beginning of mankind, since the dawn of consciousness.

When images spark fear–why? And at what point might they spark faith? Staring into the angel in the clouds, how we might wish for our suspension of disbelief to kick in and startle us back into our bodies?

On the other hand, Roest’s title might allude to another, slightly less comforting meaning. ‘Watching over us’ might not be construed in the religious sense, but rather in the constant presence–or absence–of a power that looms above. Barael, with its swirling bruise-colored clouds and wide-eyes, might lurch toward an omniscience observing our sins, our daily lives. And there’s an element of probability that can’t be ignored–if captured a moment later, depending on the course of the winds, these original images might have been very different. We might have missed them altogether. The dates of the cloud postings on the Internet span years yet each image is a stamp in time, just like the lands below are seamlessly stitched together from various historical paintings, dates and times unknown, places loosely referenced. Roest cites Northern Dutch landscape paintings as well as the work of Volodymyr Orlovsky and Isaac Levitan as key influences. Here, new forms and classical art tradition are reproduced and married in paint.

The eye immediately registers angelic shapes and forms. We see past fluffy clouds, blue sky, skinny strip of land. Our minds work with models of reality, not reality itself, Roest argues. One might even recognize some of the original source images considering the paintings are imitations, exaggerations and violations of photos that live on the internet. Lelahel seems to float on the azure blue and grassy hills of the infamous Microsoft desktop (which in itself is a reference to 19th century landscape painting) and Memuneh is not formed of clouds but by their angel-shaped absence, backlit by the streaming sun. Roest takes it to the next step by asking the viewer to join this next permutation: paintings that were memes that were photos that were angels that were clouds.

The magnitude of reality continues to thwart and baffle our attempts to understand and accurately represent it. How might an artist enchant us into manufacturing a reality in which, for better or worse, we are watched over by angels?

Zans Brady Krohn