Andréa Spartà

Early Birds Leave Rotten Fruits

exhibition view

Advertisement

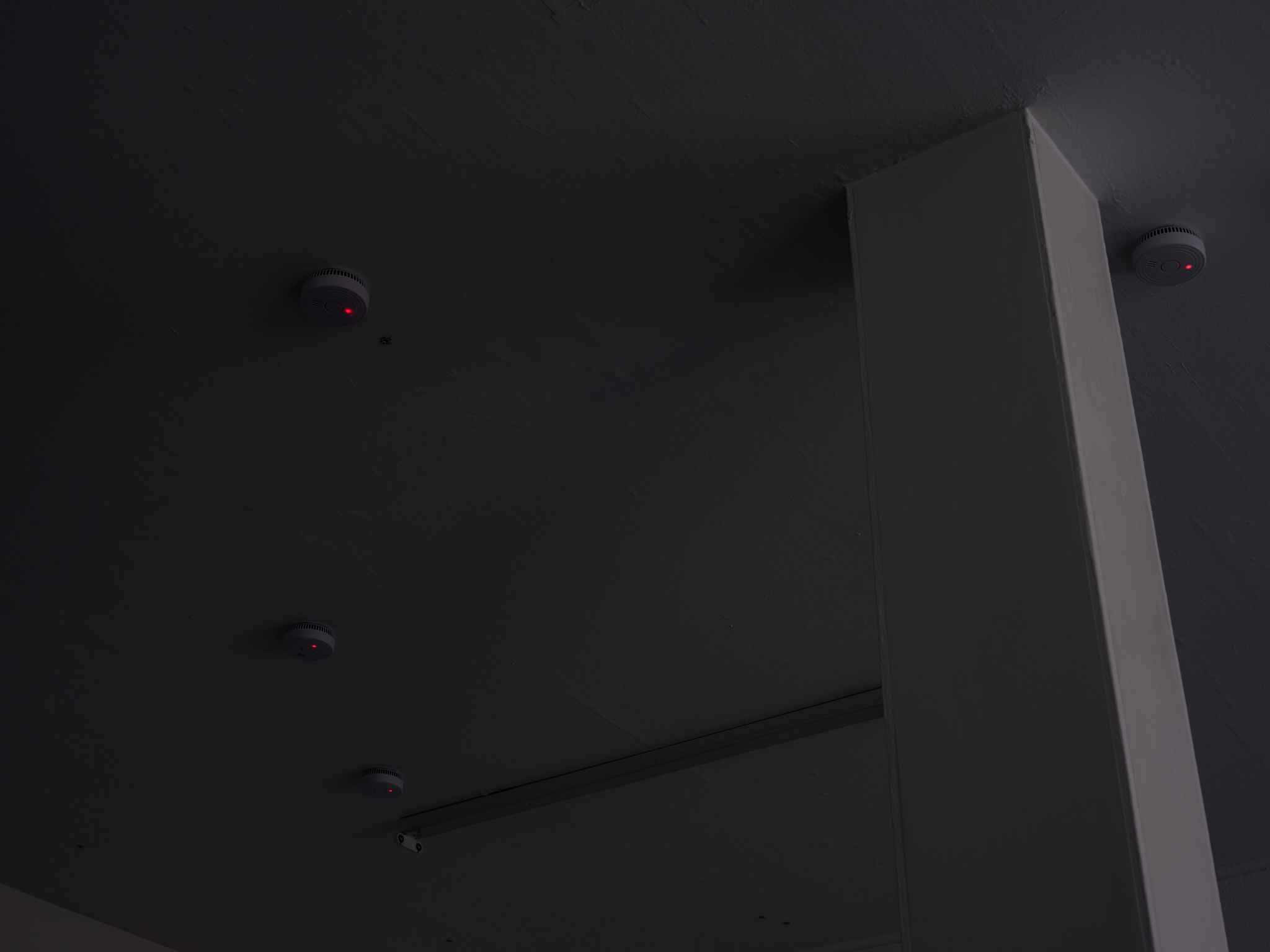

Andréa Spartà, untitled, altered smoke detectors, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, altered smoke detectors, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, altered smoke detectors, 2024

exhibition view

Andréa Spartà, Peak and decline, porcelain figurines, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, millet branches, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, millet branches, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, millet branches, 2024

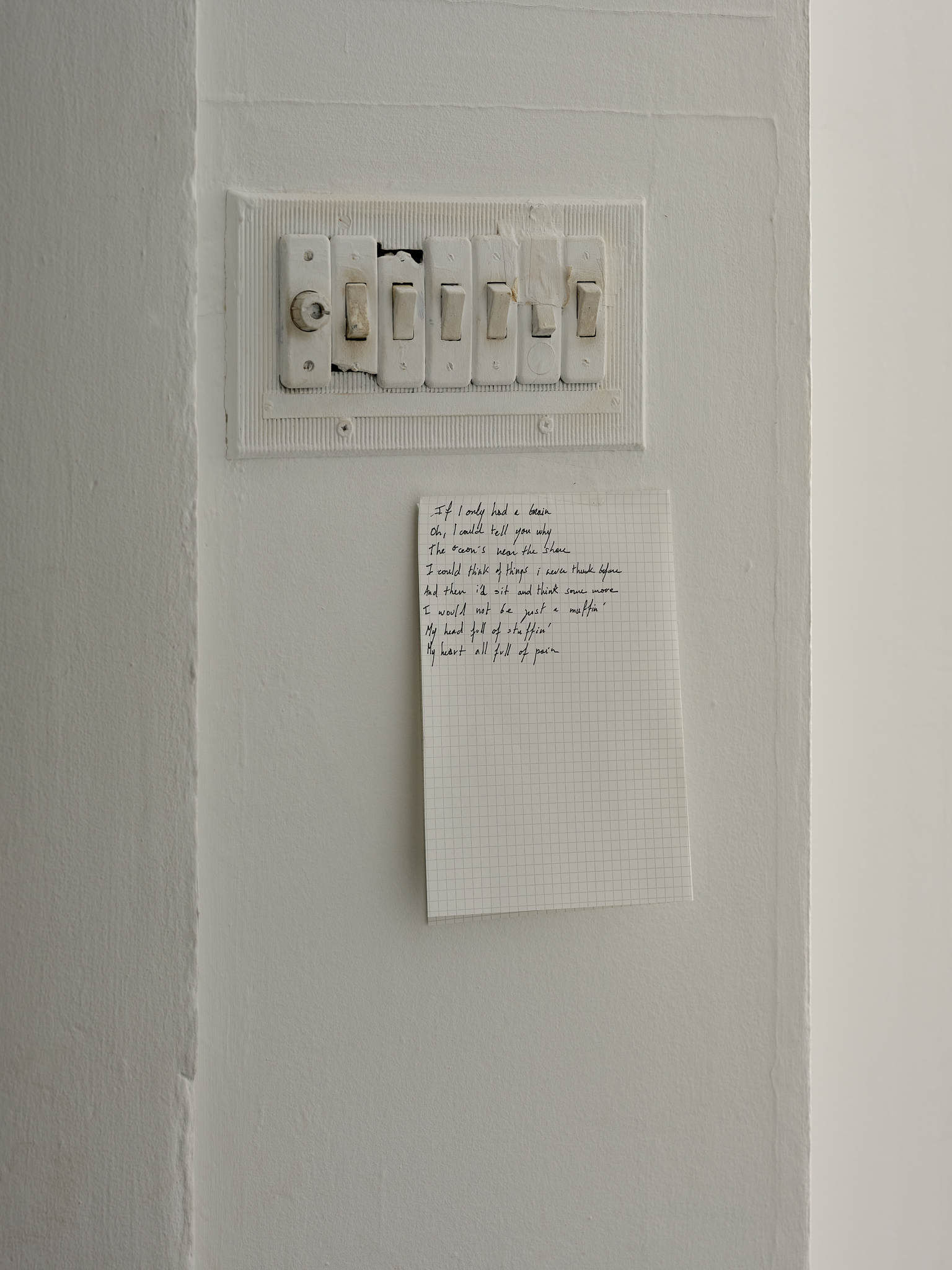

Andréa Spartà, untitled, lyrics of 'if I only had a brain' by Yip Harburg, handwritten by a friend, 2024

exhibition view

Andréa Spartà, untitled, elements of the exhibition space’s office, rearranged, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, elements of the exhibition space’s office, rearranged, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, elements of the exhibition space’s office, rearranged, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, elements of the exhibition space’s office, rearranged, 2024

Andréa Spartà, untitled, elements of the exhibition space’s office, rearranged, 2024

exhibition view

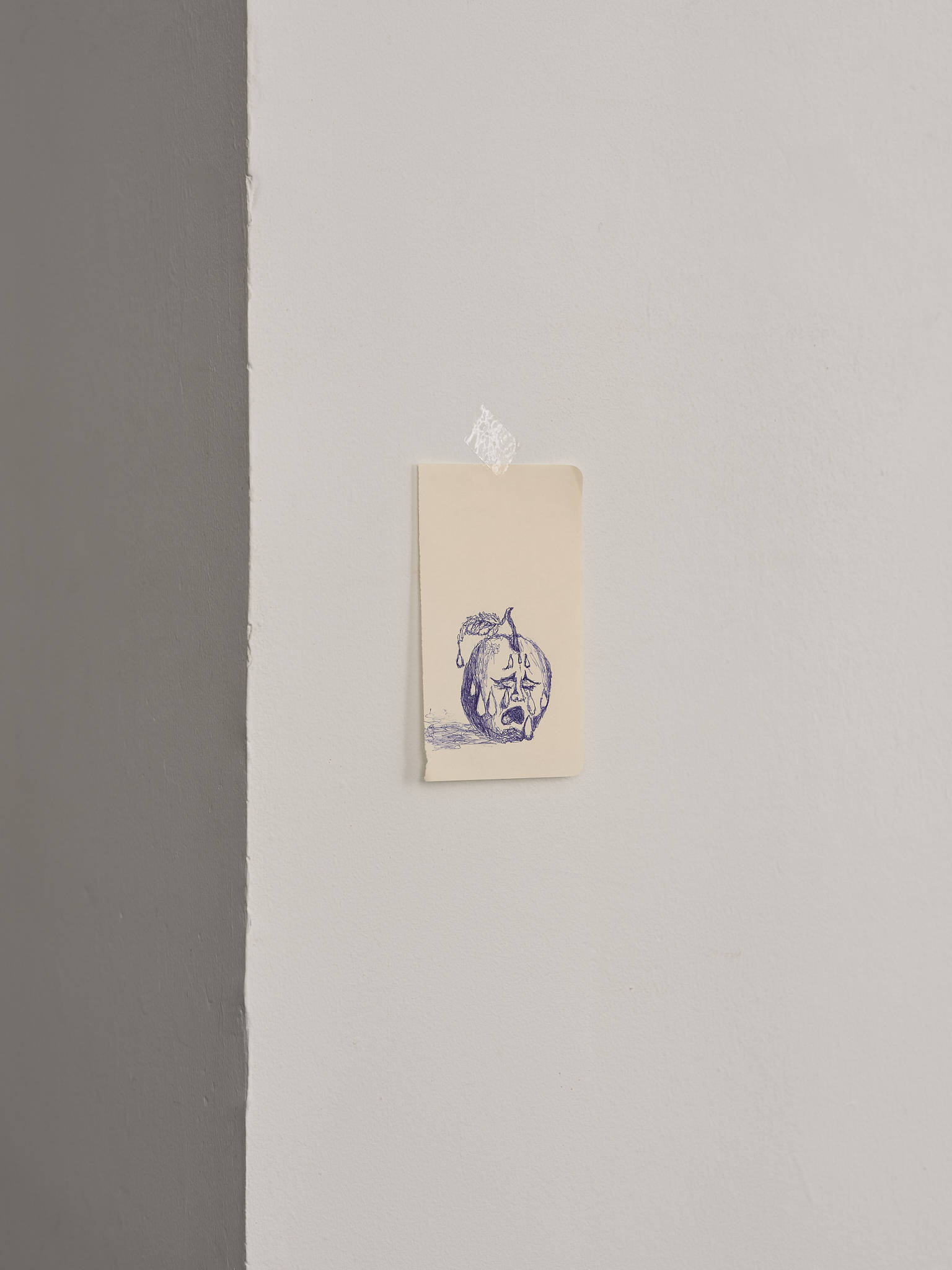

Andréa Spartà, untitled, ballpoint pen reproduction on paper of an image produced by AI from a description of the exhibition project, 2024

exhibition view, The neon lights in the exhibition space are removed; as evening falls, night descends within the exhibition.

Andréa Spartà, untitled, altered smoke detectors, 2024

Pierre Ruault My head all full of stuffin, my heart all full of pain.

The exhibition "Early Birds Leave Rotten Fruits" marks, in my opinion, a

departure in Andrea Spartà's practice. Like a whispered confession, it reveals a

more introspective tone, albeit reserved, in his work. Through our regular exchanges,

we shared the experience of being prone to severe migraine attacks that immobilize

us. This ailment is temporarily accompanied by a disenchantment with existence,

brutally and directly affecting the surrounding environment. For Andrea, this physical

and psychological pain takes shape in the central figure of the exhibition, embodied

by the Scarecrow from "The Wizard of Oz" (1939). This image particularly moves

me, as in his quest for a brain, this character oscillates between deep despair and

contagious joy. Much like him, Andrea is receptive to the new poetic dimension that

emerges from his observation of the world during these episodes. Despite the

discomfort, suffering seems to detach things from reality, offering a renewed

perspective filled with possibilities.

The halo of artificial lights distorts my field of vision, a violent intrusion into the

privacy of my retinas, repetitive, like an uninterrupted percussion. The back of my

eye sockets painfully burns. My once cooperative tools of work turn into formidable

adversaries. Automatically, I shape two shells with my hands, attempting to make

them airtight, with the goal of isolating my gaze from the environment assaulting it. At

the same time, I engage in a series of exercises, a choreography of repeated blinks

and eye rotations, in a futile attempt to restore some balance in the overwhelming

discomfort.

Andrea Spartà crafts environments from carefully collected fragments of

reality. He selects modest objects – electrical outlets, household sheets, posters of

classified ads found on the street, etc. – that have struck him during chance

encounters, seemingly without apparent reason, except perhaps a form of empathy

towards them. The essence of the artifact, for him, does not lie in the normative

dimension imposed by a utilitarian function but rather as an autonomous mass

existing freely in the world, endowed with its own physical singularities, embodying

something almost more real. From these findings, he weaves mental representations

by manipulating various visual and poetic threads. First, the spatial arrangement of

identical objects in abnormal quantities is revealed, arranged without apparent logic.

The accumulation of small smiling figurines with outstretched arms, representing the

Scarecrow, creates a disturbing tautological play capable of destabilizing our

understanding. This strangeness is also repeated on the ceiling, with an unusual

profusion of suspended smoke detectors. The incessant flashing lights,

independently generated by these machines, form a strange asynchronous

constellation. Simultaneously, Andrea conceives various installations using pre-

existing domestic materials at the Limbo site, such as crates of sheets, a ream of

paper, and a green plant. These artistic gestures, initially discreet and almost

insignificant in their arrangement and shapes gradually reveal themselves in a set of

particularly dynamic exploratory domains as the gaze lingers.

Eye fatigue, insidious, spreads from my eyes to the defenseless expanse of

my skull. Simultaneously, the sound thickens around me, turning every noise into an

unbearable cacophony. A distant laugh, the muffled murmur of a conversation, the

delicate brushing of a glass on a table, all become shrill cries in my ear. Migraine,

like a silent gangrene, takes hold of my head. I find myself powerless, lost in an

inhospitable environment.

In the end, Andréa Spartà's approach consists of creating a subtle fold in the

space of reality, influencing both the repurposed object and our position as

spectators, in order to confer another presence to things. The domestic simplicity

emanating from his works evokes a strange sense of melancholy, without a clear

source, a sensation similar to what we feel after reading the very last page of a novel

or returning from a journey.Approaching a mimicry too excessive to be entirely

sincere, the Scarecrow emerges again. But this time, it is accompanied by the

torrential tears of a neurasthenic fruit, generated through the intervention of artificial

intelligence and then captured in a small drawing taped to the wall at child's height.

These figures seem to carry within them the melancholy that disrupts space. One

day, Andréa confided in me that he feels a possessive anxiety in his daily life, an

anxiety closely linked to the heavy burden of responsibility he feels towards the

objects around him. The use and separation of these objects appear to him as both a

mourning and a relief.

The hours ahead stretch out before me, the headache depriving me of my

professional or social obligations. To be honest, I am indifferent to it all. At this very

moment, my only desire is to escape from the world, to immerse myself in a silent

solitude, engulfed by darkness in total passivity. I engage in a methodical ritual:

every electronic device, from the microwave to the phone charger, from electrical

outlets to the smoke detector emitting the slightest glow, is invariably unplugged in

the apartment.

I am reminded of Henri Michaux's collection "Bras cassé" (1973). In the

suffering caused by an accident, the poet experiences another way of being in the

world, which he calls his "left self": "The one who is the left of me, who has never in

my life been the first, who always lived in retreat, and now alone remains, this placid

one, I kept turning around, never ceasing to observe him with surprise, me, brother

of Myself." I believe that the Scarecrow draws its essence from a similar perspective.

It is this same curiosity that Andréa feels for this other, both a stranger and yet his

own.

Lying in my bed, I await the liberating sleep. Migraine deprives me of my

usual escapes: watching a movie, reading a book. I am forced to share an intimacy

with my thoughts and my anxiety: "My head all full of stuffin. My heart all full of pain."

The echoes of the song "If I Only Had a Brain" sung by the Scarecrow occasionally

resonate in the room, a rare consolation tolerated when the pain allows. "If I only had

a brain!" The room becomes an inviolable shelter, where each object, gradually, gets

lost in the darkness under indistinct shapes and blurred outlines. Suffering transports

me into a novel experience of reality, stretching its ethereal veil around me. My

room, transformed into a new zone, reacts with a captivating strangeness to its own

environment, creating an altered reality that fascinates me.

1 Henri Michaux, "Bras Cassé," Paris: Fata Morgana, 1973, p.17

Pierre Ruault