Andrea Magnani

Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori

Project Info

- 💙 Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio

- 💚 Giovanni Rendina

- 🖤 Andrea Magnani

- 💜 Giovanni Rendina

- 💛 Andrea Piffari

Share on

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio. Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Advertisement

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio.

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio. Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio. Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio.

Andrea Magnani, Trapezio Gallery presenta Lo Sguardo Fuori, 2024, exhibition view at Gelateria Sogni di Ghiaccio. Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Gustavo Romeoni, De quoi parles-tu?, 1973, 2024. Bronze, digital print on paper, acrylic and oil paint on wood. Variable dimensions, 32 x 27 x 15 cm (bronze).

Andrea Magnani, Gustavo Romeoni, De quoi parles-tu?, 1973, 2024. Bronze, digital print on paper, acrylic and oil paint on wood. Variable dimensions, 32 x 27 x 15 cm (bronze).

Andrea Magnani, Gustavo Romeoni, De quoi parles-tu?, 1973, 2024. Bronze, digital print on paper, acrylic and oil paint on wood. Variable dimensions, 32 x 27 x 15 cm (bronze).

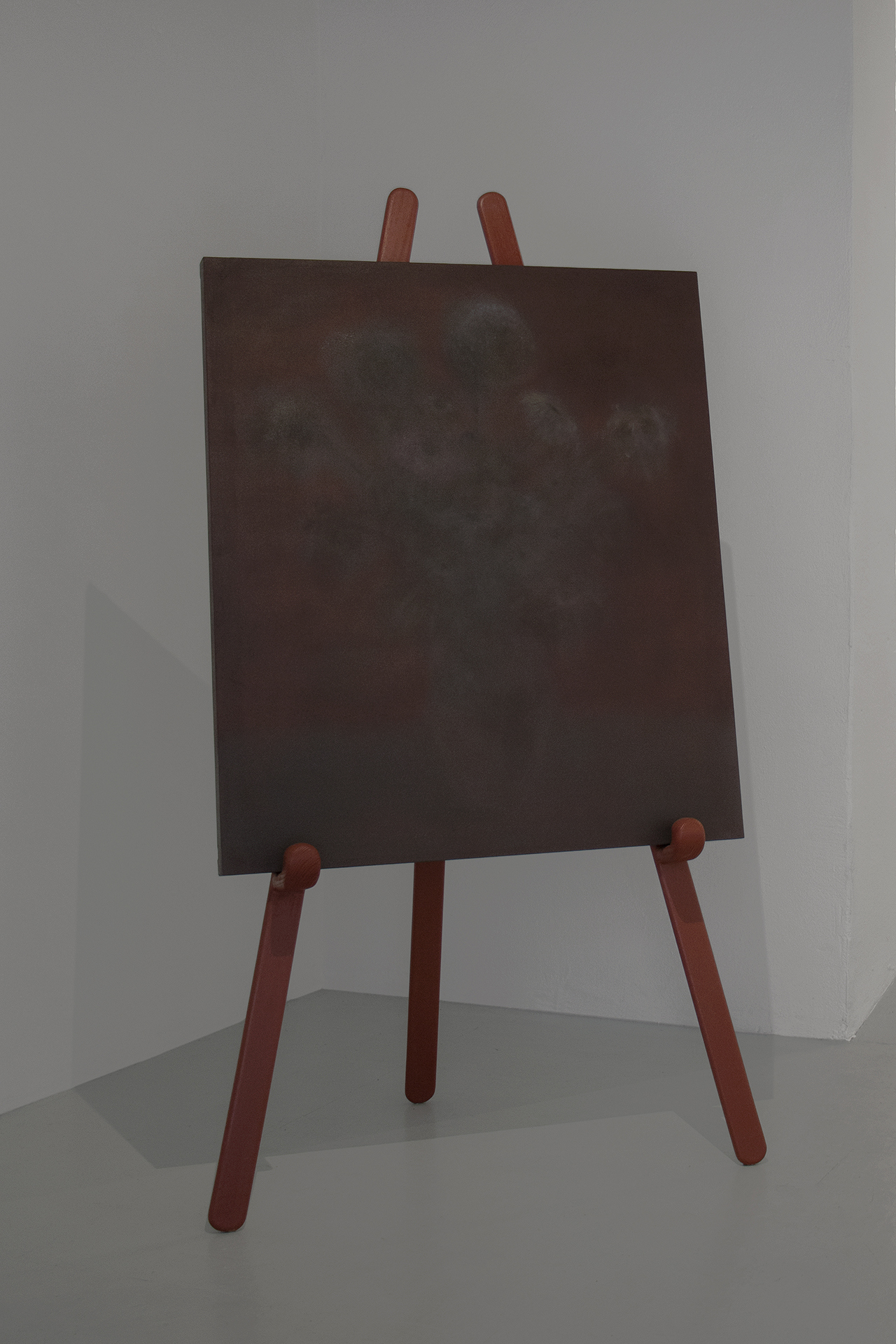

Andrea Magnani, Théo van Breukelman, Nachtelijke Bloemen, 1989, 2024. Oil on canvas, painted wood, metal. 91,5 x 105 cm (painting). Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Théo van Breukelman, Nachtelijke Bloemen, 1989, 2024. Oil on canvas, painted wood, metal. 91,5 x 105 cm (painting).

Andrea Magnani, Magdaleno Marcu (Magno), Portioncule, Erasure No. 1, 1938, 2024. Pencil on paper, digital print on paper, artist’s frame. 29,7 x 29,7 cm (drawing), 46 x 53 (frame). Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Magdaleno Marcu (Magno), Untitled No. 13, circa 1939-1955, 2024. Pencil on paper, artist’s frame. 29,7 x 29,7 cm (drawing), 46 x 46 (frame).

Andrea Magnani, Magdaleno Marcu (Magno), Untitled No. 9, circa 1939-1955, 2024. Pencil on paper, artist’s frame. 29,7 x 29,7 cm (drawing), 60 x 60 (frame).

Andrea Magnani, Magdaleno Marcu (Magno), Untitled, circa 1939-1955, 202. Pencil on paper. 100 x 70 cm (drawing), 107,2 x 77,2 (frame). Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, SHUT THE FUCK UP AND WORK, 2024. Laminated wood, plastic, digital print on paper, uv print on mobile phone cover, mobile phone. 120 x 53 x 77 cm.

Andrea Magnani, SHUT THE FUCK UP AND WORK, 2024. Laminated wood, plastic, digital print on paper, uv print on mobile phone cover, mobile phone. 120 x 53 x 77 cm.

Andrea Magnani, SHUT THE FUCK UP AND WORK, 2024. Laminated wood, plastic, digital print on paper, uv print on mobile phone cover, mobile phone. 120 x 53 x 77 cm.

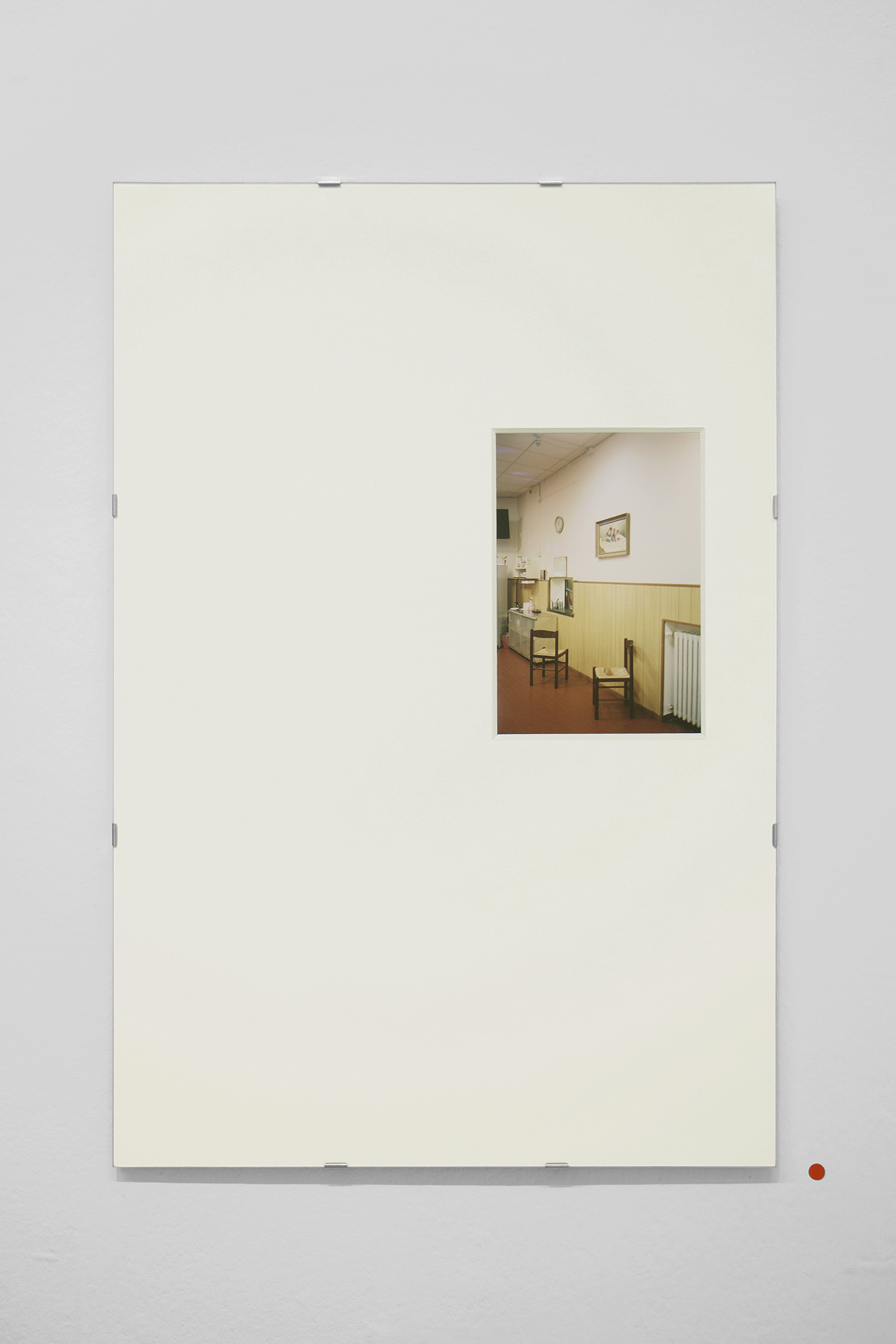

Andrea Magnani, Letizia Distante, Quattro automobili non inquadrate, 1993, 2024. Chromogenic print, artist frame. 11,4 x 17 cm (photo), 66,5 x 61 x 5,5 cm (frame). Photo: Andrea Piffari.

Andrea Magnani, Letizia Distante, Al circolo dei Franchi Bevitori un gruppo di tredici persone ballano danze di gruppo, 1999, Sold, 2024. Chromogenic print, artist frame, sticker. 12,2 x 18,4 cm (photo), 40 x 60 cm (frame).

Art=Life=Ouch

When an artist decides to write a biography or tell their story, they select, or rather construct, elements through which they define themselves. These elements are summarised, lengthened, shortened, twisted, kneaded, extinguished, and ignited. The way in which artists and art communicate, in fact, alongside various artefacts, consists of a series of sta- tements that serve as a corollary to the work, defining it and contributing to its construction. We could therefore assert that alongside formal values, there are discursive values that intertwine with them. This mode is adopted not only by many artists but also by just as many exhibition spaces.

Often, if it concerns a commercial exhibition space, the choices regarding these narratives are shaped by a precise plan aimed at an economic function. “We are interested in emphasising its historical or formal relevance.” “We are interested in whether the artist appears more or less politically aligned.” “We are interested in making them appear sufficiently ‘exotic’.” A similar discourse could be said for institutional exhibition spaces. In such cases, narrative constructions are often realised for reasons of historicising artistic heritage or for the institution’s engagement in a political sense. Just to give a few examples, we could mention the valorisation of the nation, inclusivity, and raising awareness on environmental issues.

So, a doubt arises. What does the independent space do? Once it is understood that commercial and public institutions have their own mission, for which they set in motion like a machine that produces narratives, it remains to be under- stood why an independent space activates a procedure entirely similar, made up of openings, photographic documen- tation, exhibition leaflets, etc.

“Because art is life!” a fool would respond. Certainly foolish is the one who has not realised that they are constructing themselves through artistic modalities that are nothing but a manner, a practice, a gesture as normal as clocking in. With the difference that if art is life, the time clock is never punched, and one is always in a constant chain of self-pro- duction. The self thus becomes somehow controlled by the need for success, with all that entails. Processes of appa- rent politicisation, self-exoticisation, cosy friendships, ass-kissing, and bitter smiles.

Instead, staging allows the artist to close up shop at a certain hour and return to the world to mind their own fucking business.

Giovanni Rendina

-

Trapezio Modern and Contemporary Art Gallery is delighted to unveil its new exhibition space in Bologna with Lo Sguardo Fuori. The artists featured in this exhibition have been carefully selected from among many in the gallery’s collection by its director, Luigi Canè, for their unique perspective on the tangible and their contemplative poetics.

Letizia Distante (1971), often referred to as the most undisciplined “student” of Ghirri, has always sought to reprodu- ce the grain of the photographs of the Emilian master. However, the subjects and the texture reveal a quick glance and an unruly approach to framing. For example, the series on display, Non Inquadrati, ‘89-’99, reflects the artist’s interest in the concept of subject. The suspended atmosphere of the images evokes the idea of a puzzle to be solved. These, aided by their titles, seem to recall the presence, or rather the looming presence, of the subject on the scene, nearby but outside the frame. Her compositions, which could evoke everyday scenes, romantic or joyful moments, remain elusive, leaving it to the viewer to bring them to completion.

Gustavo Romeoni (1927 - 2008), primarily trained as an engineer, was a self-taught sculptor. For years, he was part of the Circolo di Santo Spieno, a group of painters and sculptors from the lower Lazio region. There, in addition to his works, he is primarily remembered for leading the project to rebuild the sewers of the Valle del Sacco, in which

he directly participated in the design of the fine manholes, which still bear abstract, almost scribble-like decorations today. The sculpture on display, titled De quoi parles-tu?, was first presented at the Anagni festival in 1973. The event gave Romeoni brief international success, leading him to exhibit in major European capitals, especially Paris. De quoi parles-tu?, one of the few bronzes remaining in Italy, was used as a doorstop in Fausto Canè’s studio. After its redi- scovery, the Trapezio team worked on its restoration, also recovering the original title and dating.

Théo van Breukelman (1964) moved to Italy in 1987, visiting to retrace the steps of the Dutch painters Pieter and Roeland van Laer’s journey in Italy. Moving to Rome, he was able to delve into the history and works of the Bamboc- cianti School, which the two Dutch brothers were part of in the 1600s. Van Breukelman is fascinated by this group of painters mainly because of the subversive charge of their approach to painting and choice of subjects. This fascination with revolutionary art led van Breukelman to paint Nachtelijke Bloemen’ in 1989. During those years, the painter questioned how the absence of light could give rise to a new iconoclastic painting practice, leading to a new technique of painting subjects in the dark.

Magdaleno Marcu (Magno) was born in 1917 in Marseille. A semi-forgotten master, he was previously credited with being a precursor of abstract expressionism (and a certain type of Fluxus approach). More recently, following histo- rical and artistic reinterpretations, he has been studied for the value of his research on sacred themes and icons. The exhibition features four works, two from the Blooming phase, one from the Black phase, dating between 1939 and 1955, and a rare Erasure from 1938. In this last work, the artist adopts a cancellation approach similar to what - only several years later - Robert Rauschenberg would apply in his Erased de Kooning Drawing in 1953. By several scho- lars, these works have been interpreted as the result of a “controlled” iconoclastic outburst that seized the artist once the works were finished. Magno - the artistic name under which he signed almost all of his “American” works - was one of the most mysterious and controversial artists of the 20th century, and only in recent years - also thanks to the digitization of the Thomas Hess collection at the Smithsonian Institution - has he been included in the contemporary debate between figuration and abstraction.

Giovanni Rendina