Liza Jo Eilers, Maxwell Volkman, Caroline Douville

HYPNOS

Project Info

- 💙 Espace Maurice

- 💚 Marie Ségolène C Brault

- 🖤 Liza Jo Eilers, Maxwell Volkman, Caroline Douville

- 💜 Jeanne Randolph

- 💛 Manoushka Larouche

Share on

Caroline Douville, Ghostly archives: Félicia (2024) Acrylic and image transfer on canvas, 16 x 70 in

Advertisement

Caroline Douville, Ghostly archives: Félicia (2024)

Liza Jo Eilers and Caroline Douville, Hypnos Installation View

Liza Jo Eilers, Phantasmagoric at February (2024) Acrylic, gouache, glitter, graphite, colored pencil, pigment transfer and hydrochromic ink on canvas, 22 x 35.5 in

Liza Jo Eilers, Phantasmagoric at February (2024)

Caroline Douville, Seau d'Eau (2024) Acrylic on canvas 16 x 70 in

Caroline Douville, Seau d'Eau (2024) Detail view

Maxwell Volkman & Caroline Douville, Hypnos Installation View

Maxwell Volkman, Installation View

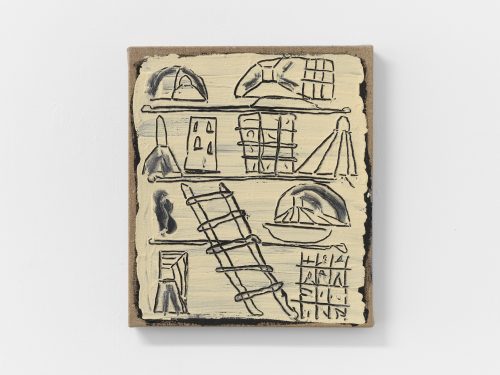

Maxwell Volkman, SWEET LEAF (2023), acrylic, inkjet prints, uv varnish, cut paper, colored pencil, and handwriting paper on canvas. 35 x 32 inches

Maxwell Volkman, SWEET LEAF (2023) Detail View

Maxwell Volkman, SWEET LEAF (2023) Detail View

Maxwell Volkman, GEEKED (2024) Acrylic, inkjet prints, uv varnish, cut paper, colored pencil, and shooting targets on canvas. 35 x 32 inches

Maxwell Volkman, GEEKED (2024) Detail View

Maxwell Volkman, GEEKED (2024) Detail View

Hypnos, Installation View

Liza Jo Eilers, Again, Out Getting Ribs (2024) Detail View

Liza Jo Eilers, Again, Out Getting Ribs (2024) Side View

Liza Jo Eilers, Again, Out Getting Ribs (2024) Acrylic on linen. 15x 18in

SPLENDIDE MENDAX

It is nevertheless vouchsafed to the few to salvage from the

whirlpool of their own feelings the deepest truths, toward which

the rest of us have to find our way through tormenting uncertainty.

— S. Freud

There is a story that circulates among psychoanalysts, a favourite story of Freud’s. After many generations you will hear somewhat different versions. This story, as Freud told it, was apparently an ancient myth. Surprisingly no one ever forgot that the myth was always prefaced by Freud quoting St. Augustine’s insight that, “Truth dwells in the inward man.”

Freud, as we know, would stroll with his daughter Anna to the Landtmann Coffee House in Vienna every evening after the family dinner. An hour later, when they returned to 19 Berggasse, Anna would go to her bed and Freud would enter his study, muttering a phrase from Heraclitus, “All serious thoughts are discovered during the night.” He would ponder his antiquities until 1:00 or 2:00 a.m., or ponder his own dreams and the dreams of his analysands. From these he created his theory of The Subconscious, which he would often illustrate in lectures by recounting this favourite very ancient myth. Around 1899, when The Interpretation of Dreams was published, or soon thereafter in the early twentieth century, Freud persuaded himself that his analysands (everybody actually) are impelled by a dimension of their psyche even more covert than the Subconscious — the Unconscious. Until this momentous theoretical revision, the myth Freud loved to expound, as a depiction, allegorically of course, of the Subconscious, went something like this:

There were three daimones who lived deep inside a sacred cave, and each one was uniquely powerful.

One of these cave-dwelling imps was able to infect entire villages with a splendide mendax, which can be translated as “glorious falsehood,” a delusion that caused the citizens to see each other as stereotypes of beauty or virtue or blue blood. Neighbours and kin were then no longer recognized as the familiar flawed and domesticated peasants they had always been. Everyone was ardently desiring everyone to be as sparkling and flat as a Byzantine icon, to be a luminous distraction from their frustrating, lacklustre lives. Everyone pursued everyone in a mass hysteria of berserk fandom.

The second of the cave-dwellers had the power to transform every, or any, word such that it meant its exact opposite. This was not only perplexing to the philosophically-minded citizens but also to those whose preference had always been to take everything literally, to accede to the maxim, “It is what it is.” The philosophs found themselves debating about Non-Being when they thought they were debating about Presence, and found themselves offering a definition for “accidental” when they intended to define “inevitable.” The rest of the townsfolk found themselves trying, for instance, to talk about an egg but to be remarking instead about a chicken; and most alarming, instead of describing a dead guy lying in his casket they would describe him upright in a trance shuffling through an olive grove.

The third daimon would inflict a massive patricidal compulsion randomly upon sons in a seemingly ordinary family (at this Freud apparently would exhale a dense cloud of cigar smoke and intone “Mala gallina malum ovum”,* implying additional vile maternal influence, yet actually revealing his ambivalence toward his own mother.) The accursed sons’ resentment, envy and rage would suddenly ignite a murderous compulsion; engorged with venom the sons beat their father to death with a chariot axle. The sons’ hate of authority burned so ferociously that they even hated truth: everything they uttered about the murder, Freud said, was “splendide mendax,” which can also be translated as “stupendous lies.”

* From a bad hen, bad eggs

Jeanne Randolph