Alexandra Tretter

antiGone

Project Info

- 💙 Kunstverein Heppenheim

- 🖤 Alexandra Tretter

- 💜 Johann Peter Eckermann

- 💛 Chris Bierl, Ulrike Weinberger

Share on

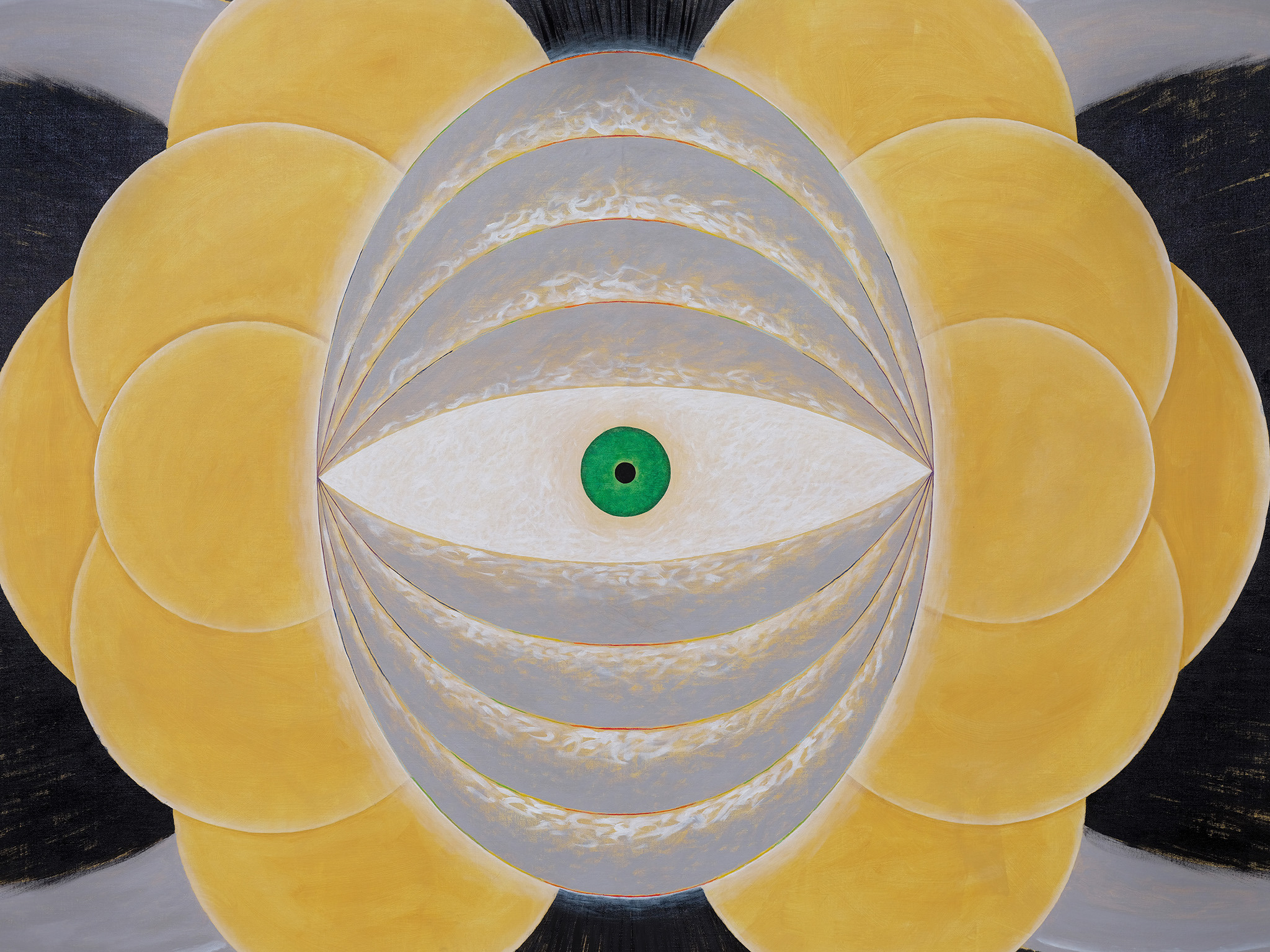

Alexandra Tretter: Antigone, Acrylic on linen, 212 x 666 cm, 2024

Advertisement

Alexandra Tretter: Detail Antigone right

Alexandra Tretter: Detail Antigone center

Alexandra Tretter: Detail Antigone left

Installation Shot Alexandra Tretter: Antigone @ Kunstverein Heppenheim

Installation Shot Alexandra Tretter: Antigone @ Kunstverein Heppenheim

Installation Shot Alexandra Tretter: Antigone @ Kunstverein Heppenheim

Installation Shot Alexandra Tretter: Antigone @ Kunstverein Heppenheim

Installation Shot Alexandra Tretter: Antigone @ Kunstverein Heppenheim

Conversation between Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Peter Eckermann

Wednesday, March 28th, 1827

Eckermann:

I brought back to Goethe the book by Hinrichs, which I had read attentively. I had also gone once more through all the plays of Sophocles, to be in complete possession of my subject. [...]

What he says about Creon's conduct, appears to be equally untenable. He tries to prove that, in prohibiting the burial of Polyneices, Creon acts from pure political virtue; and since Creon is not merely a man, but also a prince, he lays down the proposition, that, as a man represents the tragic power of the state, this man can be no other than he who is himself the personification of the state itself—namely, the prince; and that of all persons the man as prince must be just that person who displays the greatest political virtue.

Goethe: (returned with a smile)

Besides, Creon by no means acts out of political virtue, but from hatred towards the dead. When Polyneices endeavoured to reconquer his paternal inheritance, from which he had been forcibly expelled, he did not commit such a monstrous crime against the state that his death was insufficient, and that the further punishment of the innocent corpse was required.

An action should never be placed in the category of political virtue, which is opposed to virtue in general. When Creon forbids the burial of Polyneices, and not only taints the air with the decaying corpse, but also affords an opportunity for the dogs and birds of prey to drag about pieces torn from the dead body, and thus to defile the altars—an action so offensive both to gods and men is by no means politically virtuous, but on the contrary a political crime. Besides, he has everybody in the play against him. He has the elders of the state, who form the chorus, against him; he has the people at large against him; he has Teiresias against him; he has his own family against him; but he hears not, and obstinately persists in his impiety, until he has brought to ruin all who belong to him, and is himself at last nothing but a shadow.

Eckermann:

And still, when one hears him speak, one cannot help believing that he is somewhat in the right.

Goethe:

That is the very thing, in which Sophocles is a master; and in which consists the very life of the dramatic in general. His characters all possess this gift of eloquence, and know how to explain the motives for their action so convincingly, that the hearer is almost always on the side of the last speaker.

One can see that, in his youth, he enjoyed an excellent rhetorical education, by which he became trained to look for all the reasons and seeming reasons of things. Still, his great talent in this respect betrayed him into faults, as he sometimes went too far.

There is a passage in Antigone which I always look upon as a blemish, and I would give a great deal for an apt philologist to prove that it is interpolated and spurious.

After the heroine has, in the course of the piece, explained the noble motives for her action, and displayed the elevated purity of her soul, she at last, when she is led to death, brings forward a motive which is quite unworthy, and almost borders upon the comic.

She says that, if she had been a mother, she would not have done, either for her dead children or for her dead husband, what she has done for her brother. ‘For,’ says she, ‘if my husband died I could have had another, and if my children died I could have had others by my new husband. But with my brother the case is different. I cannot have another brother; for since my mother and father are dead, there is no one to beget one.

This is, at least, the bare sense of this passage, which in my opinion, when placed in the mouth of a heroine going to her death, disturbs the tragic tone, and appears to me very far-fetched—to savour too much of dialectical calculation. As I said, I should like a philologist to show us that the passage is spurious.

Johann Peter Eckermann