Nino Kapanadze

The cruellest month

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Advertisement

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, I can connect nothing with nothing (Piscine municipale), 2024, Oil on linen, 2 panels — 195 × 130 cm (each). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin.

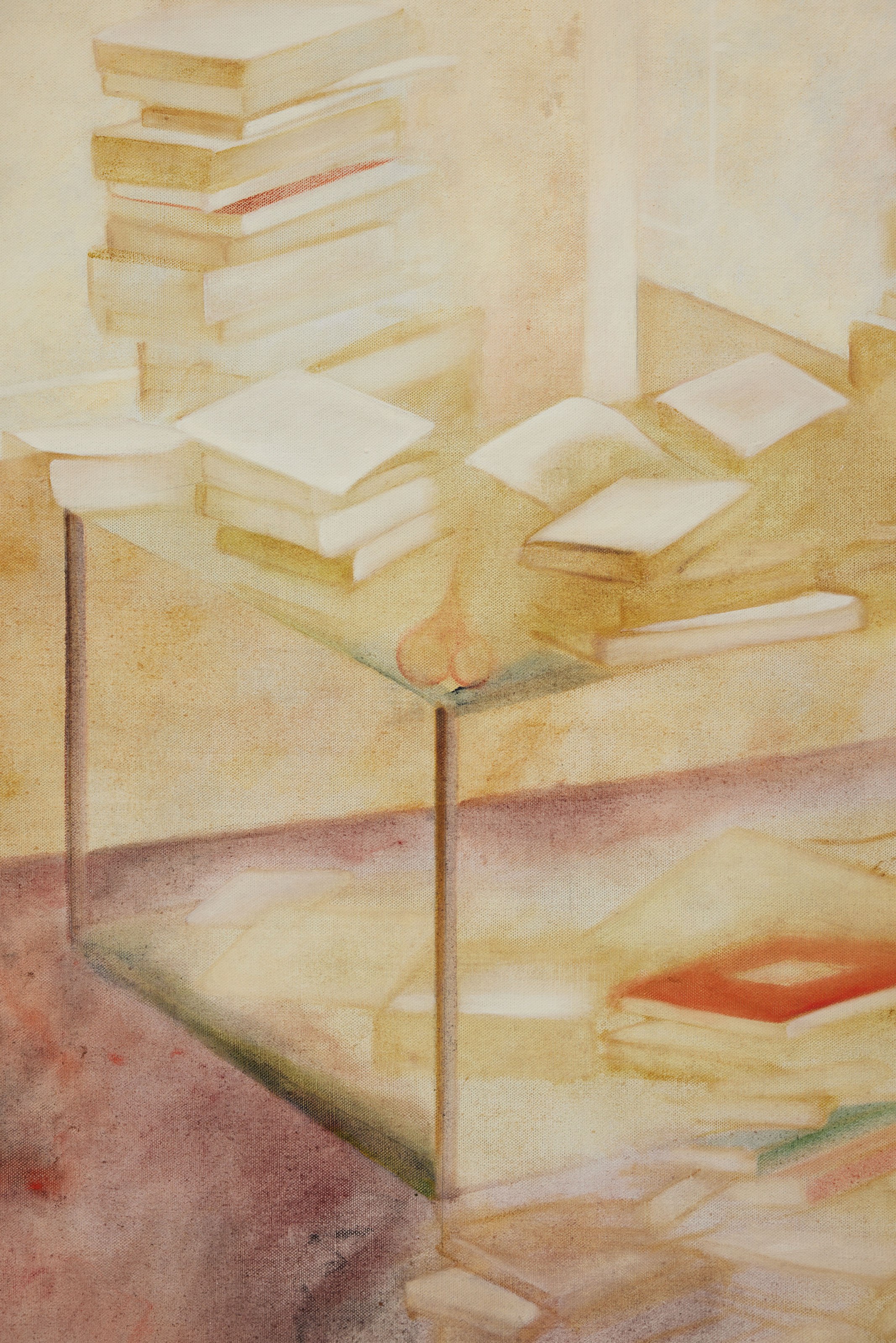

Nino Kapanadze, I can connect nothing with nothing (Piscine municipale), 2024, Oil on linen, 2 panels — 195 × 130 cm (each)(detail). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin.

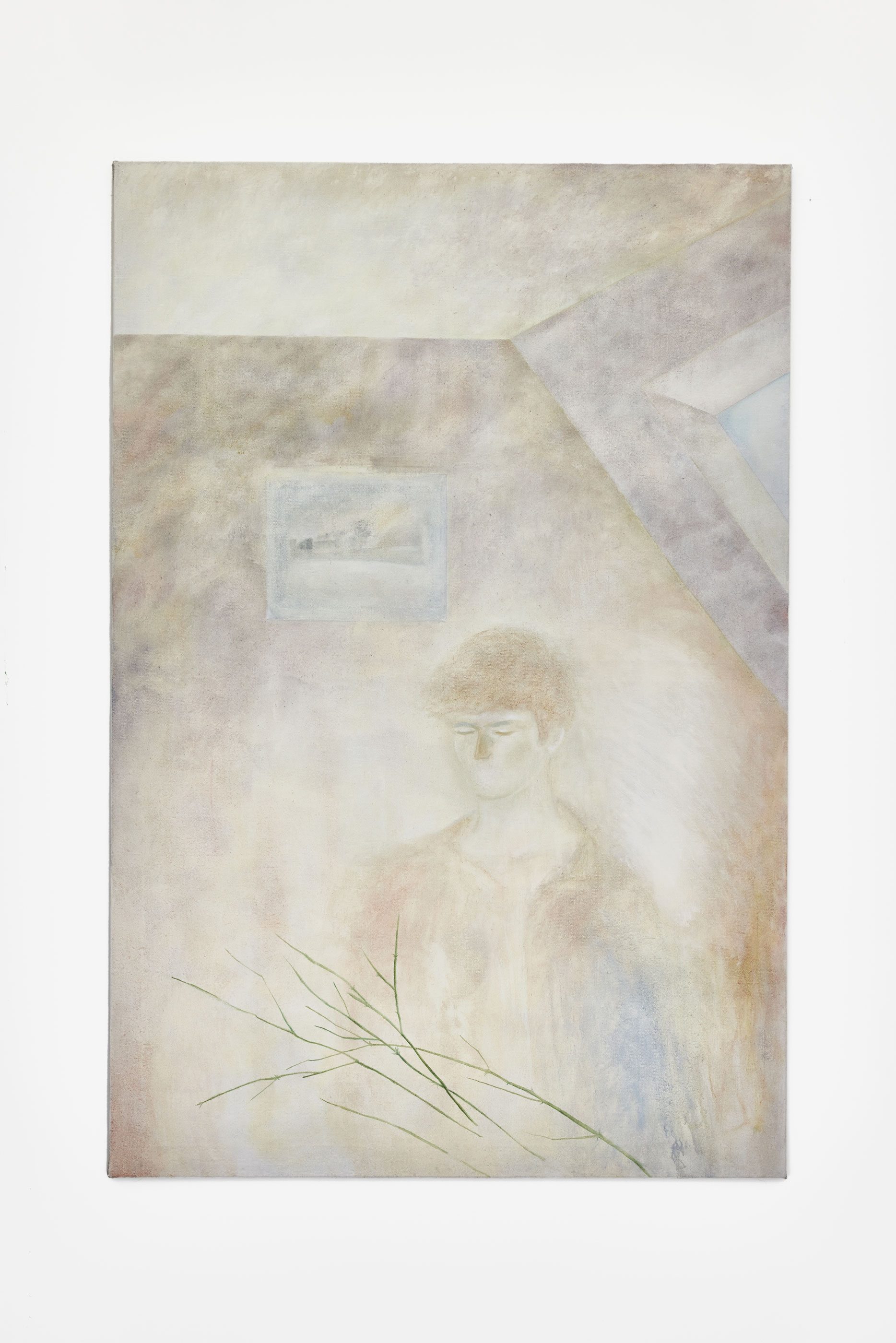

Nino Kapanadze, Interruption, 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin.

Nino Kapanadze, Interruption, 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin.

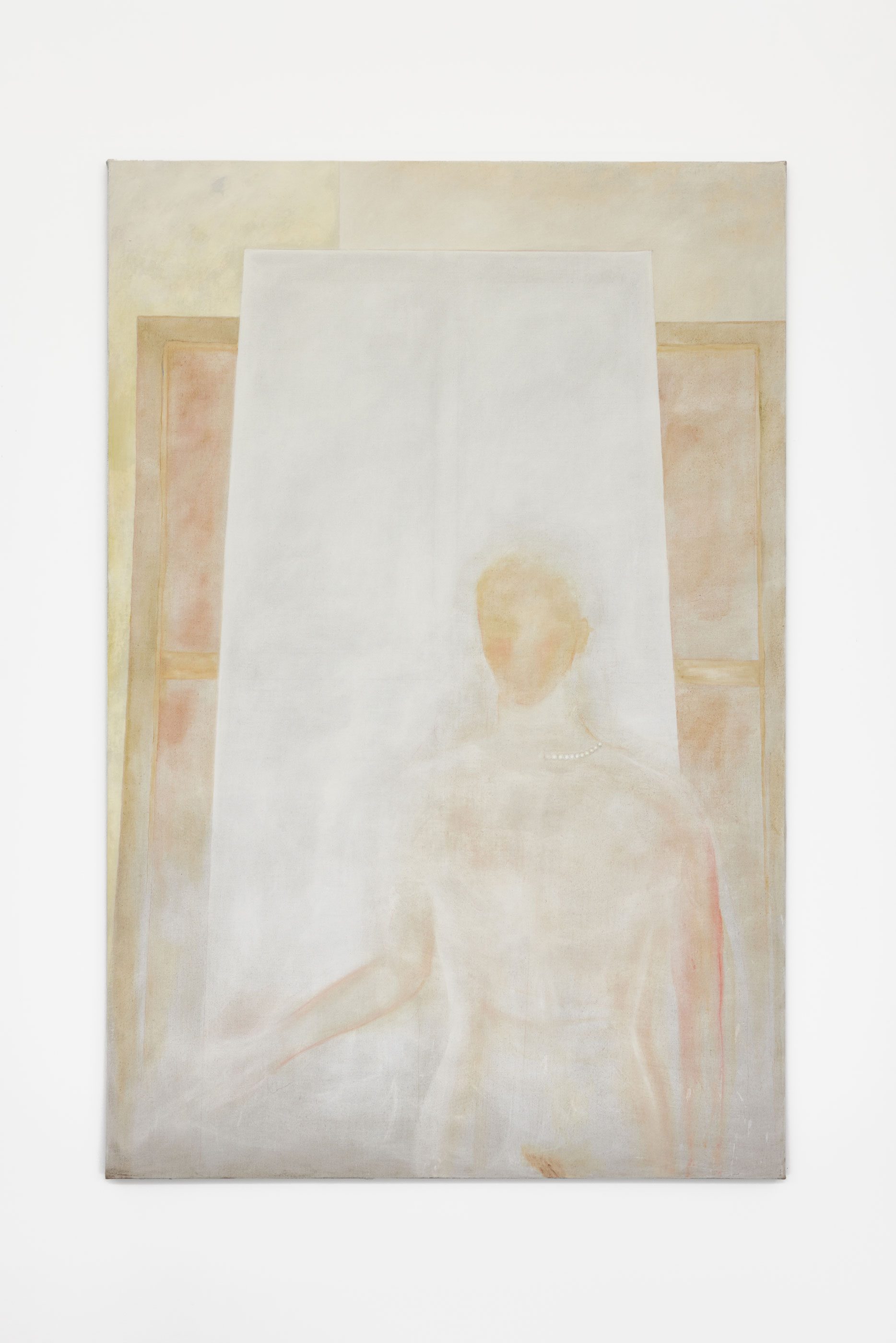

Nino Kapanadze, Those are pearls that were his eyes (Portrait of an artist), 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin.

Nino Kapanadze, These fragments I have shored against my ruins (I) & (II), 2023, Oil on linen, 27 × 22 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo.

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME, 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2023, Oil on linen, 130 × 195 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2023, Oil on linen, 130 × 195 cm (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, Rue Pergolèse, 2023, Oil on linen, 130 × 195 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, Rue Pergolèse, 2023, Oil on linen, 130 × 195 cm (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, All the lights you closed your eyes to, 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, All the lights you closed your eyes to, 2023, Oil on linen, 195 × 130 cm (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Nino Kapanadze, The cruellest month, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

The cruellest month by Nino Kapanadze

Raising colours, arising emotions

A particular tonality emerges from Nino Kapanadze’s most recent paintings, a light, an atmosphere, all the more perceptible from one picture to the next as the formats are identical – comfortable for the body that paints, welcoming to the viewer, taken vertically or horizontally. The paintings are either isolated or adjoined. Discreetly, beyond and beneath the subjects being depicted, there is a propulsion towards a purely pictorial and sensorial quest, focussed on the painted space and the emotions that may arise there. Everything here – trees, human figures, books, even walls or other architectural elements – becomes manifest as a more or less fleeting presence, an emanation, an apparition on the verge of visibility, which is in turn indicated not as. something clear, but instead an open question, constantly being raised. The treatment of colour plays a great role, with both a transparency and a fluidity, as well as the materials and the pictorial surface. While the technique is classical, oil paint on linen canvas, the use the artist makes of it produces here and there effects close to non-painting, or at least an effacement. The manner that it has been formed as in a fresco – the way of taking colours in the depth of a pictorial layering – resonates in the paradoxical density that it gives her spaces, in a continuity between them and all the various forms they contain: such are the driving forces of this delicate and yet radiant sensuality which can be felt on contemplation.

Just as the mist lifts in the morning through condensation and evaporation, as the sap rises in springtime in the trunks of trees towards their growing leaves, life, in its intense mellowness, innervates these paintings, in which the slightest green filament, the least red space, the slightest splash and the smallest blossoming become the most precious manifestations. By quoting the first line of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, “April is the cruellest month”, Nino Kapanadze gives her works a season; to be precise, she places them between the winter that witnessed their birth and the springtime that begins at the moment when they are displayed. When winter turns towards spring, such a crossing-over suggests colours, from whites to greens, of a life flowing back in a tenuous return. Like that “awakened day, which still wore the moon as a necklace like a silver gem” as evoked by Robert Walser (1), or the “stuttered-over-again world” that Paul Celan (2) attempted to convey, there can here be felt the fluttering of beginnings. And, quite naturally, we are led towards poetry and the way in which meaning arises from it, which, like a cloud, in the words of Pierre Alferi “offers itself and recedes, unfolds, holds back”: “While disengaging itself, it adopts a certain figure, like a smoke ring. Fully heard and felt, each phrase leaves behind the memory of a volume with fleeting borders, which more or less melds with previous ones. And, when looking up from the book, we can see these memories with their shifting, mobile forms, as they cohabitate, become joined or disjointed.” (3)

In Interruption we see a figure, obscured by veils, hands open over a closed book with clouds of bright colours seemingly emanating from it, as with the genie of the lamp, mottling the greater part of the surface. So, with veils, various frames (windows, tiling, encasings, crannies), whose function is not to circumscribe or block what cannot be contained, but instead to reveal, even fleetingly, what has just been inscribed within them, like those tiny white dots that form the pearls of a necklace (those are pearls that were his eyes) or fine white lines highlighting the contours of a hand and thus of a gesture, or which sketch out the curve of a shoulder and the roundness of a head. “White has a tendency to make things visible” (4), stated Robert Ryman, who wanted to paint paint, not white per se. In the same way, the use Nino Kapanadze makes of colours, which might be described as powdered, takes part in these arrangements that aim at capturing what is visible: because a ray of light is never seen more clearly than when it has been filtered and brought out by the various particles or projected images suspended in it. For, it is also light that, in a certain respect, reveals everything that is being diffused imperceptibly in the apparent transparency of the air. By trapping one another, light and dust reveal each other. Another passage from The Waste Land then comes to mind: “(Come in under the shadow of this red rock), / And I will show you something different from either / Your shadow at morning striding behind you / Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; / I will show you fear in a handful of dust” (5). This is why self-portraits are made from behind, why figures have closed eyes or half-effaced traits that have barely been sketched out: they have been absorbed within themselves and in the paint, making them resonate even more. If they close their eyes to the light (all the lights you closed your eyes to), it is to make it radiate more, to be run through, since “being is being / pierced / daylit” (6), by the light that emerges from inside the paintings, from their very materials, as in the icons that Nino Kapanadze has so often observed in the churches of her native Georgia. And this is from where, via sensations, emotions emanate, like air being breathed out and forming a mist on the surface of a mirror, disturbing reflections and signifying life.

1. Robert Walser, At Dawn. (Our translation.)

2. Paul Celan, Stuttered-Over-Again World, translated by A.S. Kline, Twenty-Eight Poems, 2014. Available online:

https://www.poetsofmodernity.xyz/POMBR/German/Celan.php#contents

3. Pierre Alferi, “Météo du sens”, Chercher une phrase, Paris, Christian Bourgois éditeur, 1991, p. V. (Our translation.)

4. Robert Ryman, interview with Susan Sollins, “Color, Surface and Seeing”, Art 21, 13 December 2006.

5. T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, Collected Poems, Faber & Faber, London, 2020.

6. P. Alferi, “douze airs”, Vacarme, n°24, 2003, p. 93. (Our translation.)

Guitemie Maldonado