Raphael Sitbon

Zugunruhe

Advertisement

Zugunruhe

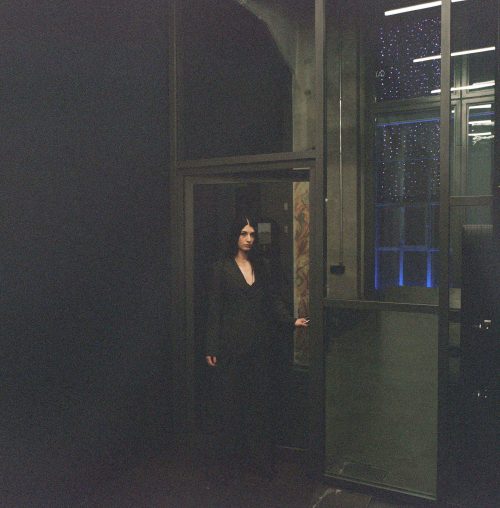

Raphaël Sitbon / La Station / 2.02-17.02.2024

From these cities will remain he who passed through them: the wind!

The house delights the eater: he empties it.

We know, we are people passing through,

And who will follow us? Nothing worth naming.

– Bertolt Brecht, From Poor B.B.(1922)

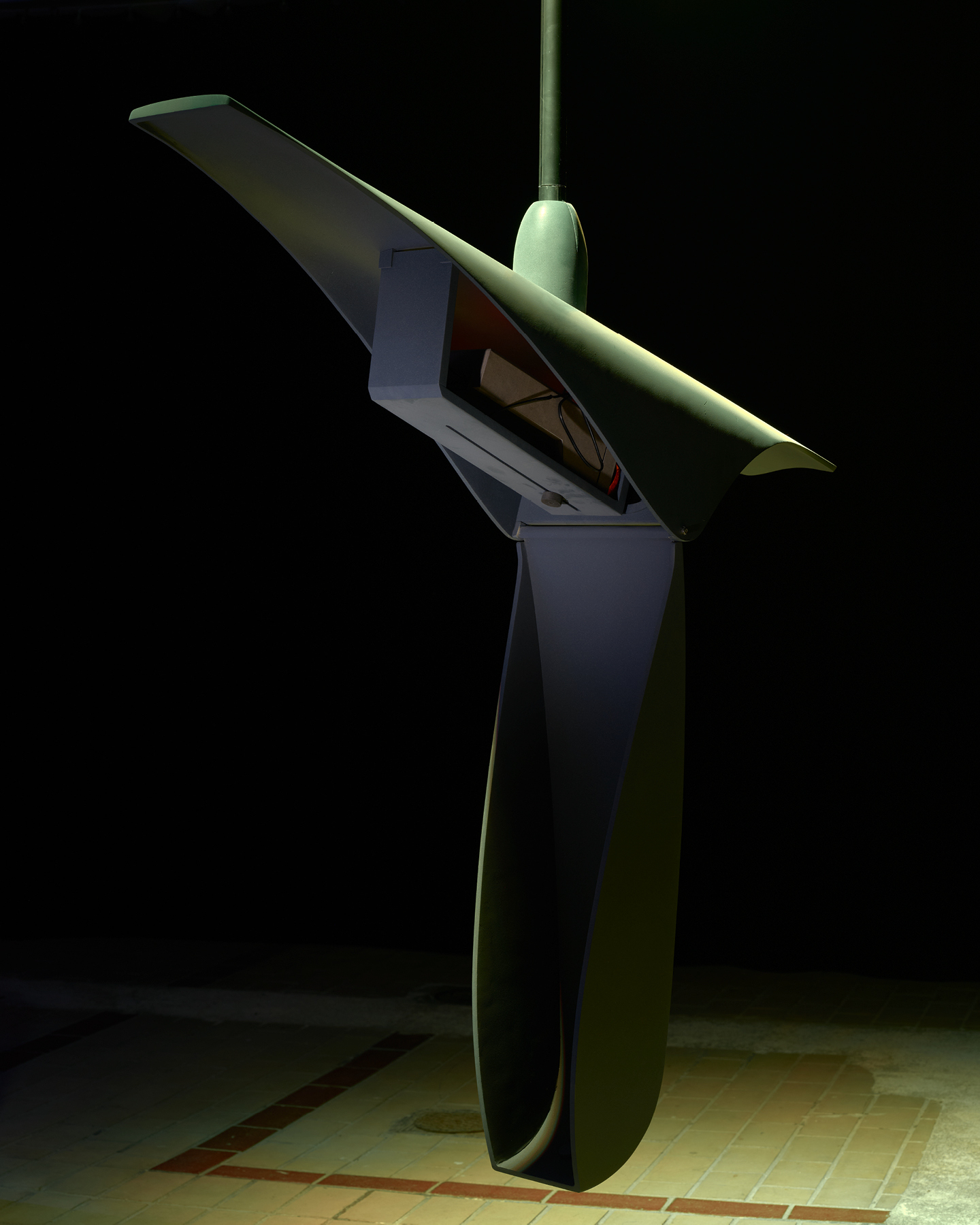

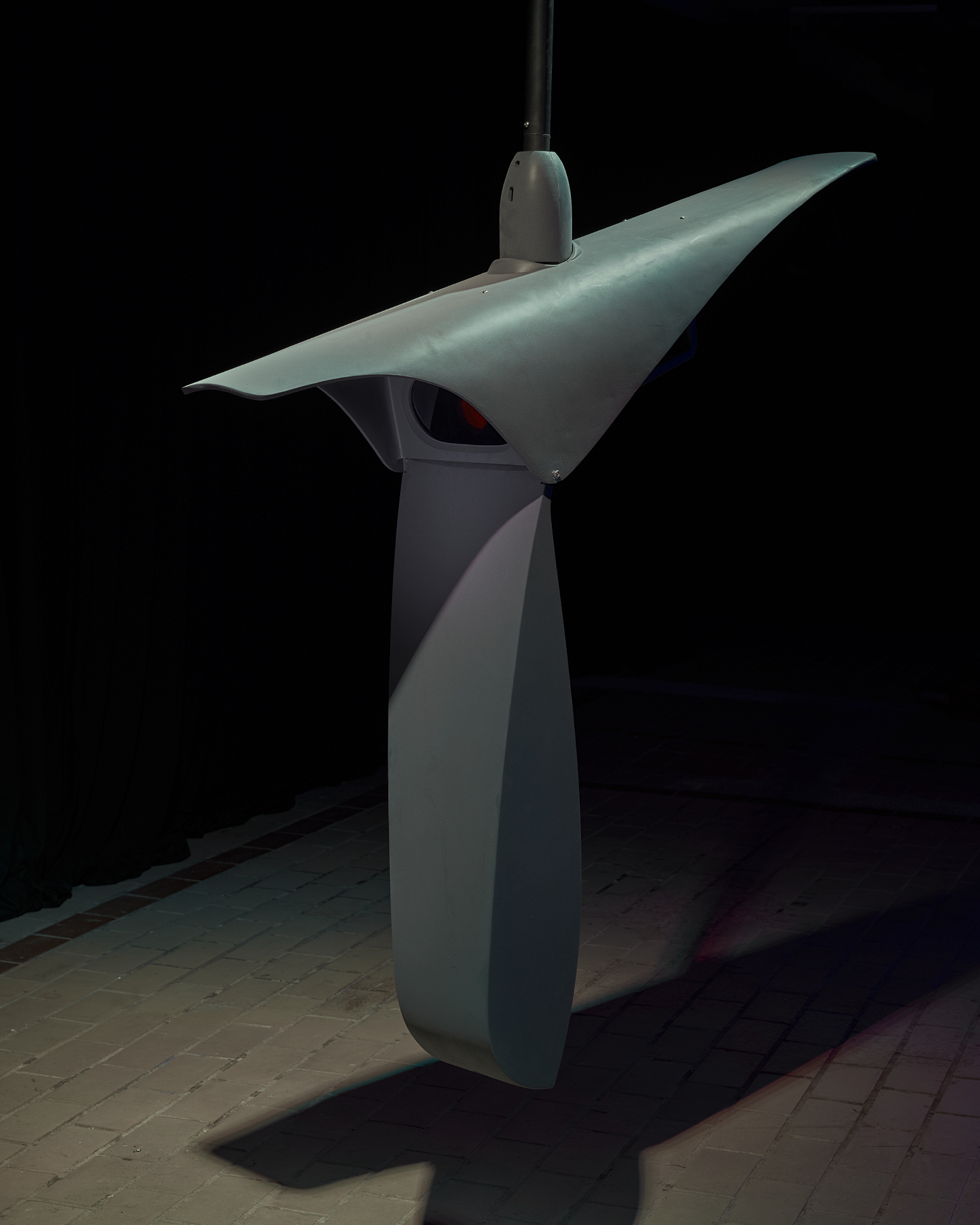

From some memories of a phone conversation, I have the tale of sleepless nights, beaks appearing in various corners, an unknown city being constructed like a set through some memories. Also remaining are counterfeit objects, others found that were deemed suitable. There’s the solitude of the wood when no one is watching, and a whole list of characters: a lamp post in velvet pants, emaciated apples, a yawning camcorder. There’s a scene like a hospital and the chance of a curtain that no longer moves. The memory of a camera hanging in the subway remains.

I hear about things done and those shown. From closets, drawers, and safes, I think of things hidden. Nestled in my toilet is a paper on the wall still held up by a bit of fixative paste. On it, the “Mahagonny notes” list the precepts of what Brecht called his “epic theater”1 - a theatrical form aimed at awakening critical thinking, preparing for political action, through a series of distancing and strangeness techniques: a narrator breaks the invisible “fourth wall” addressing the audience, songs or signs interrupt the plot, actors strive to show that they are showing - they refuse complete transformation into characters. The dramatic illusion is broken, identification prevented, the fable assumes itself as a fable, thus as fictitious. It exposes all its tools: light sources are visible, spotlights, machinery.

There’s this same desire in Raphaël Sitbon to extract mechanisms to bring them into view; to put the backstage in the foreground. And if the curtain no longer rises, it’s because it has fossilized into a sculpture. In Zugunruhe, it’s hard to say what belongs to meticulous gesture or chance encounter, to authentic or artifice. There’s the work of the hand and that of wear. There’s the pleasure of hours spent reproducing each groove, retracing each bite, and creating new ones; mimicking reality until exhausted. From certain pieces, Raphaël also tells me over the phone that they are “synthetic” - not only because they simulate objects but also because they seem to condense them. Thus one thing becomes another, then a fourth that was not initially thought of. There’s this pallet jack that is also a bed; this delivery backpack turned coffee table.

These forms exist between the sedentary and the transient, they coexist with contradictory clocks: things devoured by time, by teeth, and these cores without mold that we haven’t cleared away. Of all these meals, Zugunruhe bears the trace. It’s also that the work of sustenance has nourished the artist’s practice: mastery of wood meets his habits of surveying, of recovering images, other objects seen on the road. As if by gluttony, he has turned the exhibition into scenography. Zugunruhe brings together the lunch break, the drift, and the eagerness, the time of rest and the fever of assembly. And since we finally exhibit the reverse of these decors, we will observe twice as much; from the place where we look2, the theater of Zugunruhe is a place that is spied upon. This is what the forms of birds betray that have invited themselves among the pieces. From this scene deployed within the station, they have become discreet, voracious spectators. So above “this construction site […] [they] make rounds, come and go, watch; there are sentinels everywhere”3 . There is this camera slipped into an open mouth, ready to receive the feed. There is this feeder empty like an abandoned house. There is the swollen belly digesting the spectacle. In its languid silhouette, one could see “the assembly of sleepers”4

of the culinary theater5 spoken of by Brecht. Except that this bird is insomniac; its nap has turned into a bar sign, it has been embedded in the multicolored neon of the plexiglass. The variations in light here evoke those of moods; they reflect the restlessness of Zugunruhe, this anxiety that grips animals during migration, the disruption in their sleep cycle, their agitation coming “to dig into dusk” 6 .

From some memories of a phone conversation, I recall the image of another bird: among the species that cross the United States every autumn, the white-throated sparrow can stay awake for up to seven consecutive days. For several years, the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has been examining it7. It attempts to extract components from its insomnia, turn them into pills, and distribute them to soldiers and anyone else who wants them – to fight, work, consume, continuously. I think of false remedies, the opacity of glass when no one looks at it. I think of the camera that threatens to see everything and collapse in the subway. So what remains for me: these birds “big as barns, big as toasters,”8 Brecht’s narrators, Aristophanes’ Chorus Leader – who, already, addressed the public:

“let everyone open their eyes, let everyone be attentive! […] we hear the sound of wings there, very close by.”9

There is profit in closed eyes,

methods to better blink.

Salomé Burstein

1 See Bertolt Brecht, “Notes on the opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny” (1930) in Writings on Theater, Paris, L’Arche, 1963, translated by J. Tailleur. This is where Brecht formulates his first schematization of the opposition between “epic theater” and “dramatic theater,” which he also calls “Aristotelian,” through this table.

2 Etymologically, the Greek “theatron” – the root of the word “theater” – refers to “the place where one watches.”

3 Aristophanes, The Birds, translated by Laëtitia Bianchi, Paris, Arlea, 2024

4 Bertolt Brecht, Little Organon for the Theatre, translated by Jean Tailleur, Paris, L’Arche, 1978, p. 43;

5 By the expression “culinary theater,” Brecht refers to a theatrical form that he criticizes, namely, a bourgeois entertainment where spectators would come to digest their meals.

6 Anne Carson, Red Doc, translated by Vanasay Khamphommala, Paris, L’Arche, 2022

7 See Jonathan Crary, 24/7 Capitalism Assault on Sleep, Paris, Zones, 2014, translated by Grégoire Chamayou

8 Anne Carson, loc. cit.

9 Aristophanes, loc. cit.

Salomé Burstein