Jenine Marsh

Resurrected in Times of Need

Advertisement

Perhaps it is tired to say that Berlin is filled with ghosts, and yet...

There’s something about a place with a recent past of uprooted fascism, being at the heart of a struggle for ideological victory between East and West – it always contains those kernels despite anyone’s best efforts to purge them.

Some buildings remaining from the 15th to 19th centuries after WWII, such as the Berlin Palace, were replaced with socialist-modernist constructions like the DDR “Palace of the Republic” – rebuilt again as the current site of the controversial Humboldt Forum. Since 1443 this single building has been ruined, repaired, expanded, recaptured, demolished, and reconstructed at least 11 times, making for a surfeit of temporal layering, artifice, and sentimentality.

When the modern period was ushered in, with its undoing of largely metaphysical ideals for how society should be governed, so too emerged a preoccupation with collective memory. With immense transformations to social organization and overall living conditions, collective memory represented a theoretical means of understanding the intricate phenomena of human development and the material conditions of history marching onward. The vehicle for this understanding has been to build, and to (attempt to) destroy and rebuild.

As Adorno wrote, “the past that one would like to evade is still very much alive.”

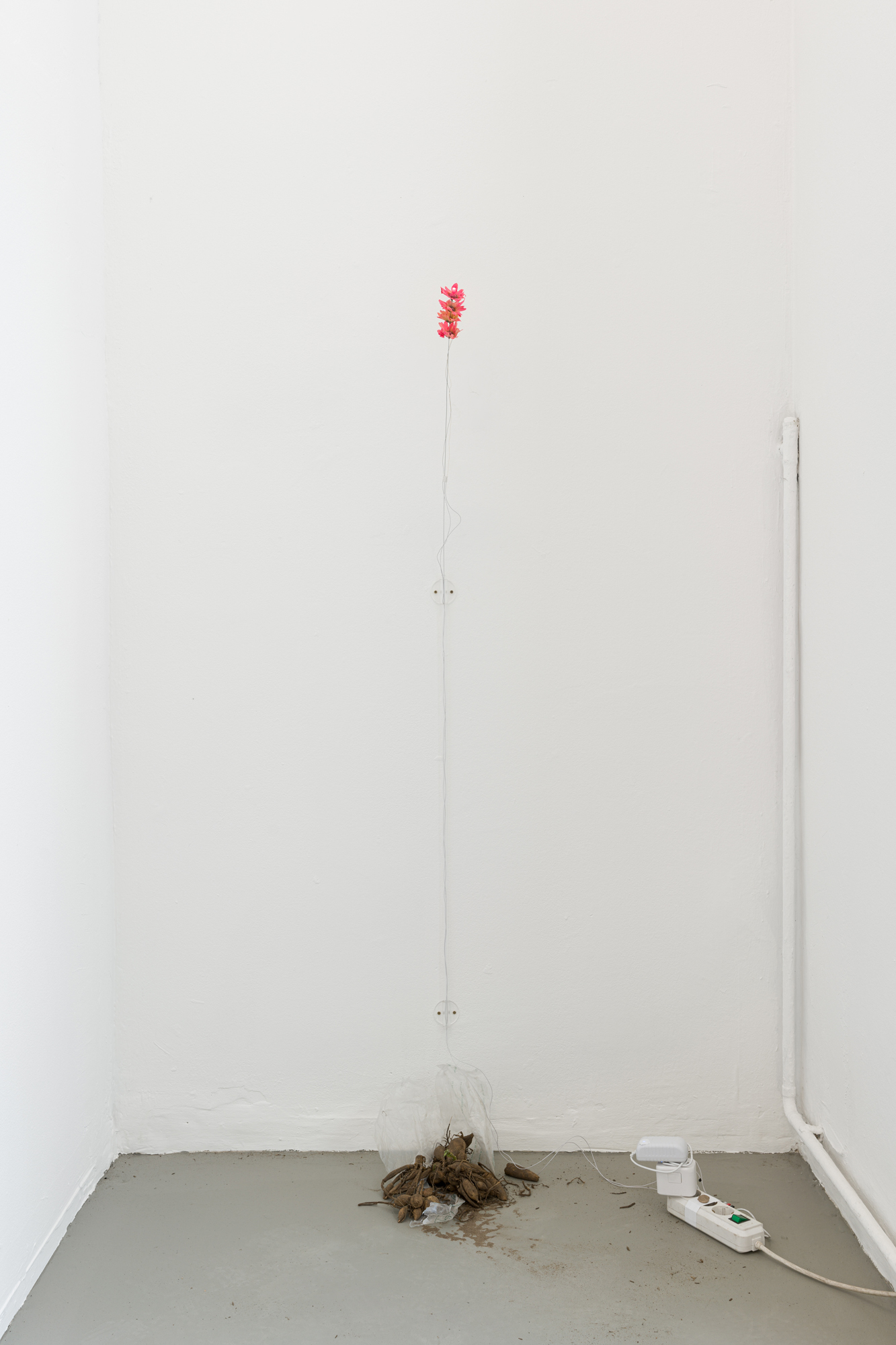

Jenine Marsh’s sculptural practice examines the shared experience of end-stage capitalism. Using elements of the everyday such as coins, flowers, newspaper, and purses along with materials that signify the labour of the built environment like concrete and bronze, Marsh highlights how economic, social, and architectural realities are tightly bound to each other. With a distinct interest in historical and literary conceptions of utopia, what often comes through is an equal consideration for the past as for the future. An overview of her artistic work reveals a poetic, cohesive feminist and anti-capitalist insight into value, agency, and mortality, evaluated through processes of research, physical contact, and personal resistance.

In this new solo exhibition, "Resurrected in Times of Need," Marsh creates a site-specific installation that addresses systems of value and memorialization, particularly related to the history of Berlin. Looking closely at the relief sculptures at the Soviet Memorial in Treptower Park, the graphic figuration of a strong, idealized proletariat is shot through with the elements of Marsh’s material sensibilities. Disembodied and sculpted in the familiar, civic medium of concrete, the forms disclose the urgency and inadequacy of their material. As the show’s title suggests, despair, optimism, nostalgia, and forgetting are cyclical parts of the collective unconscious, while Marsh’s sculptural process mirrors historical materialism where the past, present, and future may become tactile and interactive.

Here, the colossal monumentality of the solid limbs is part of an allegorical reflection on what it means to coexist with the grand arc of Berlin’s pre- and post-war histories. The open-ended gesture exists between the embodied experience of a once-living past and a still living present. Sculpture as a public medium, particularly using the didactic universality of socialist realism, is programmatic for collective memory, but in a very personal way. By taking the monumental and turning it into the intimate, Marsh plays out the push and pull of heaviness and fragility, personal and political, in front of us.

The inclusion of bronze-cast coins and trash alludes to the build-up of public participation with a monument over its lifetime, as public space is fraught within the sphere of remembrance. Preserved flowers with LED lights are optimistic in their attempts to survive, while living flowers are symbolic of how the ephemeral mediates grief and tribute in the commemorative process.

All monuments are propaganda at bottom. What comes afterwards is the constant back and forth of ideological reckoning. Memorial building and debates around what should remain, in the West particularly, have increased substantially during and after what was thought to be the end of history. But at the end of the day, all memorialization represents the experience of real people. When social relations are reduced to abstract representations, memory, value, and mortality are still inextricably linked.

Of course, the way we communicate publicly about history is prescribed and largely inadequate. These days you can pay anywhere from €17 – €380 for a several hours-long walking tour of traces of the Third Reich in Berlin, which, at a certain point, feels almost pathological.

Don’t get me wrong, looking closely at history reveals an impossible array of pathologies. Monuments, and most buildings by extension, are the external representations of how individual decisions endure through politics. Our proclivities to either remember, erase, and/or forget are similarly bound to ideology.

Through this exhibition, Marsh showcases her knowing that history is delicate. She engages us with the traces of her process and efforts of preservation. As art historian Leigh Markopoulos wrote just before her sudden passing, “historical spaces only read as [testaments to loss and absence] if the present is allowed to grow up around them, and our understanding of the contemporary is of necessity informed by both.”

Angel Callander