Helena Uambembe

On the site of the Okavango

Project Info

- 💙 Anton Janizewski

- 💚 Julian Volz

- 🖤 Helena Uambembe

- 💜 Julian Volz

- 💛 Julian Blume

Share on

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango, installation view

Advertisement

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango, installation view

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango, installation view

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango, installation view

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango, installation view

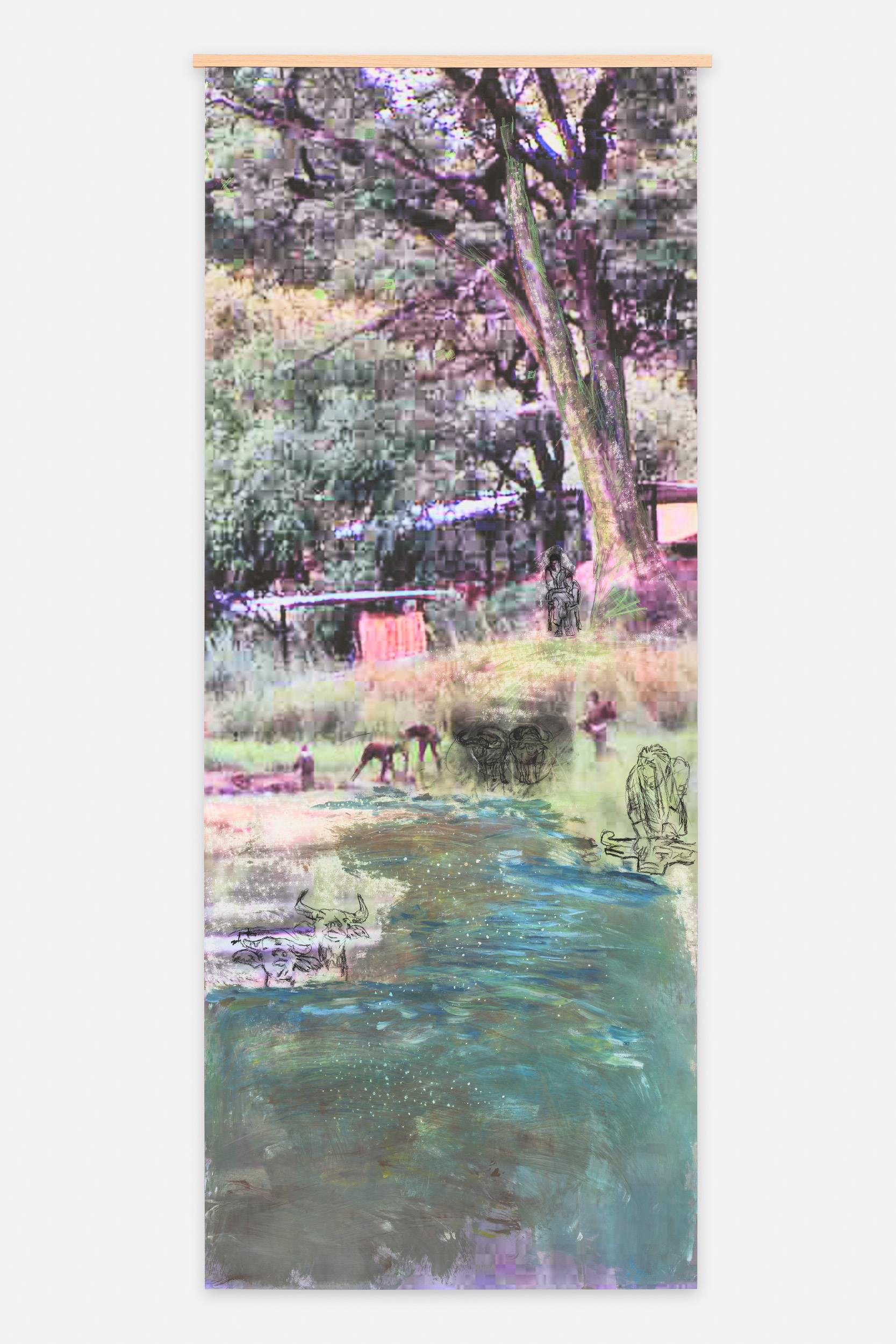

Helena Uambembe, On the site of the Okavango it was the meeting point and the division line, 2024, 200 x 80 cm

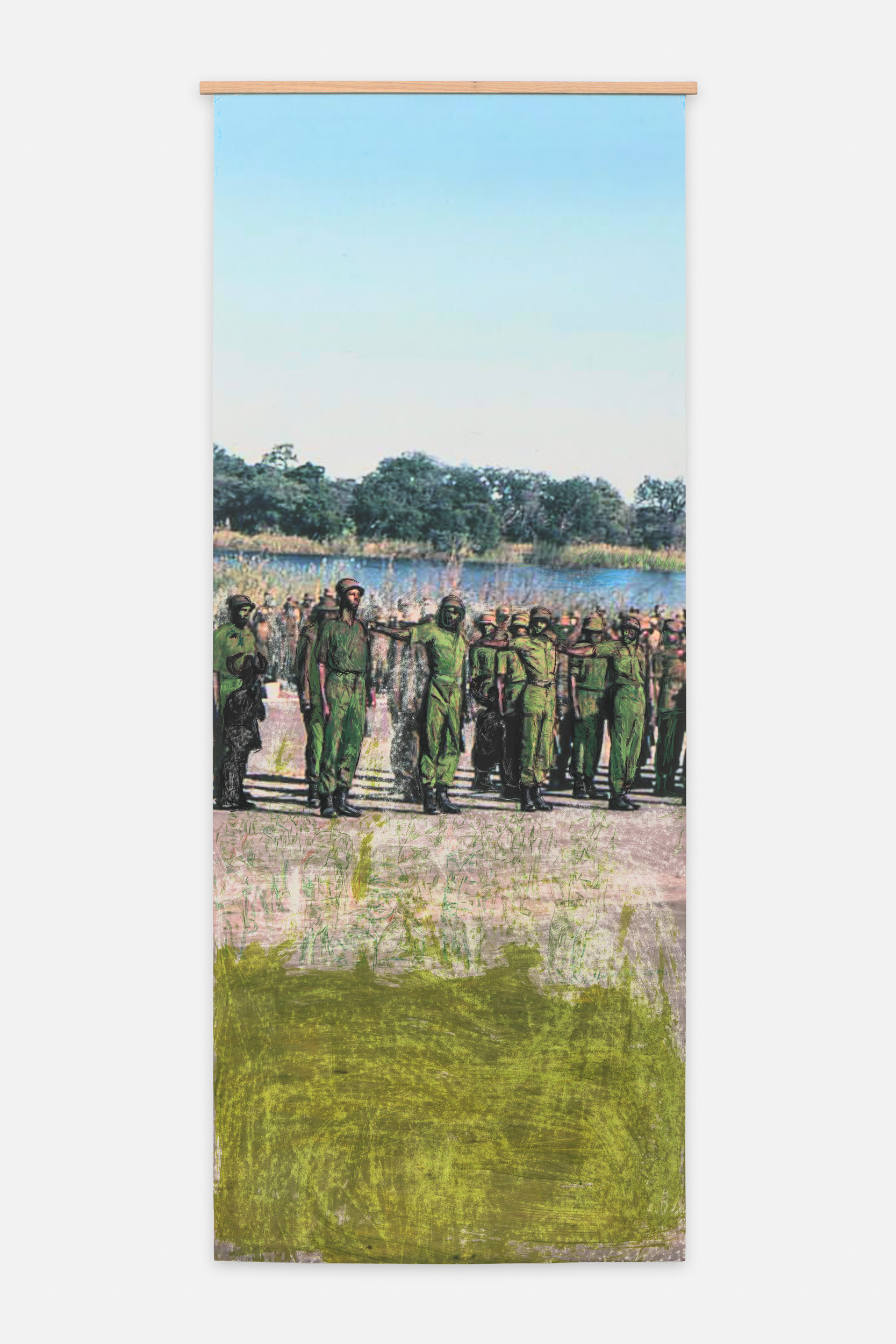

Helena Uambembe, In the river on the banks Captain is calling, 2024, 200 x 80 cm

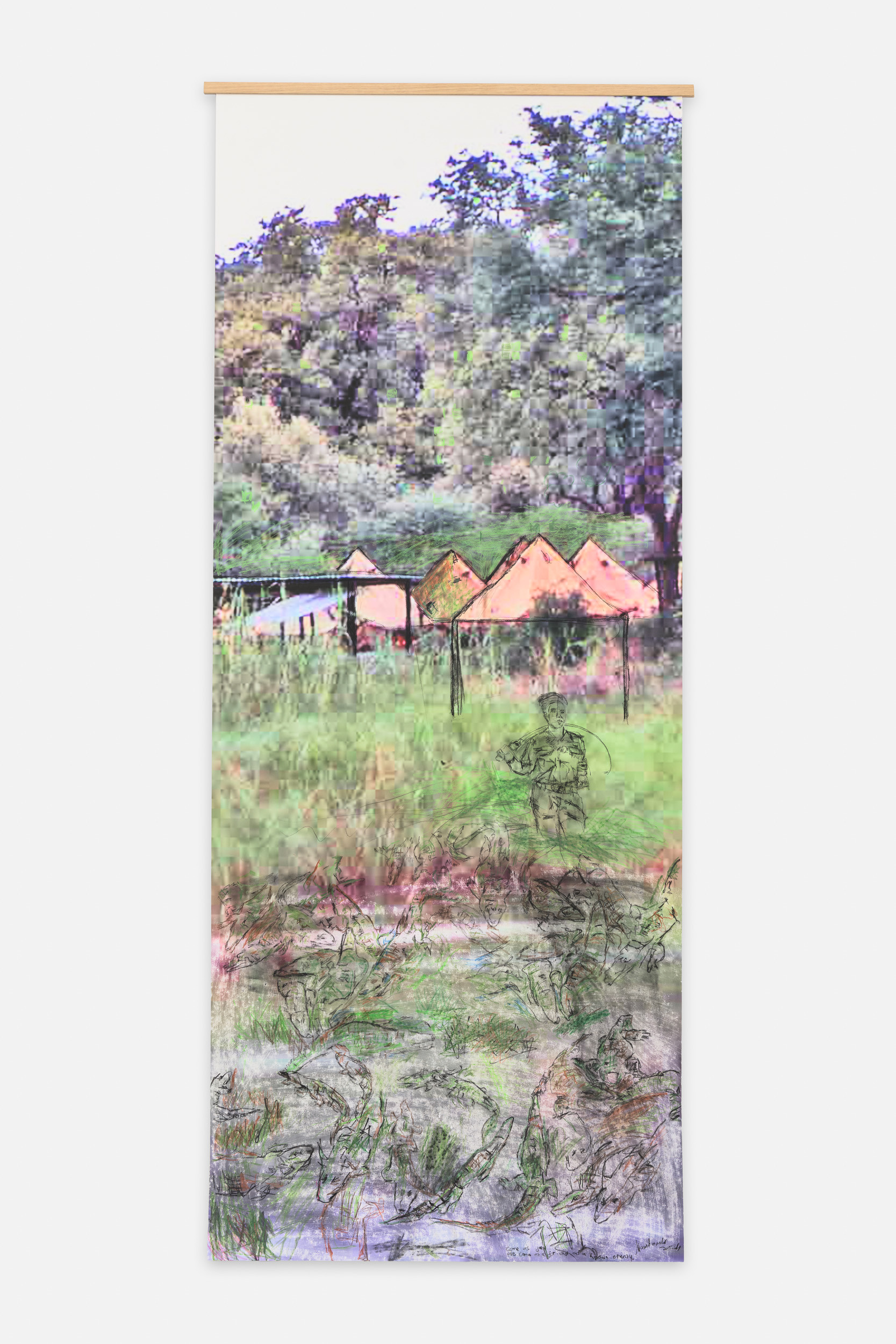

Helena Uambembe, In plain site, 2024, 200 x 80 cm

Helena Uambembe, Fresh waters, 2024, 70 x 99 cm

Helena Uambembe, When the Okavango runs dry, 2024, 100 x 104 cm

Helena Uambembe, Uma Uma, 2024, 90 x 126 cm

In her artistic works, Helena Uambembe examines how decolonization in southern Africa and the subsequent civil wars are reflected in her own private environment. The starting point for her projects is therefore always the memories, but also the traumas and amnesias of her own family and her community. While the artist, who was born in Pomfret in 1994, dealt with her home town in the South African Kalahari Desert in earlier works, in her exhibition “On the site of the Okavango” she turns to an earlier chapter of her family history. Her family lived in Buffalo, a military camp on the southern bank of the Okavango River, from the mid-1970s until the end of the 1980s as part of the 32nd Battalion of the South African Apartheid Army. Her father and uncles repeatedly crossed the border river from there to carry out military operations in Angola.

The water of the Okavango can be found in a series of six water-colors, over which Uambembe has drawn the outlines of crocodiles with charcoal pencil. The chosen technique is ideal for reflecting on the Okavango and its status as a border river between Namibia and Angola, also on a material level. The colors flow into one another in the watercolors. They even overlap without one color covering the other. Proximity and distance, inside and outside are literally blurred. The paper on which Uambembe has applied her colors also knows no clearly defined forms and boundaries. Instead, the artist has based the format of the individual works entirely on the flow of the colors. The limits and boundaries in the exhibited works are only created by the strokes of the charcoal pencil. However, the artist has also only drawn the outlines of the crocodiles, usually with a discontinuous stroke, so that these are also partially superimposed or dissolve into the areas of color. It is no coincidence that crocodiles emerge and disappear from the colored areas, as around 11,000 of them live in the Okavango. While the predators in the exhibited works become an allegory of the geographical violence that has been inherent in the border river since the time of German colonialism, the watercolors reject the arbitrarily drawn borders.

The outline of a crocodile was once also emblazoned on the upper arm of Helena Uambembe’s uncle Titto. The amateurish tattoo was also drawn in simple strokes. The patient and extremely fast-acting predator served as a model for his own activities in the ranks of the 32nd Battalion of the South African Army, which attacked the operational bases of SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization) in Angola from South West Africa (now Namibia). In its fight against SWAPO, which wanted to achieve the independence of what was then South West Africa from the South African state, the South African army in turn recruited members of the Angolan opposition who were fighting against the government of Agostinho Neto, who had ruled the country since 1975, the year of Angola’s independence from Portuguese colonialism. Thus, black soldiers ended up in the service of a racist apartheid regime, including Uambembe’s father and uncles.

In the course of her research into this convoluted history, the artist discovered the photo archive of Gert Nel, one of the former colonels of the 32nd Regiment. One photograph, for example, shows a settlement on the other side of the Okavango together with some of the residents on the edge of the riverbed. Like a crocodile, there is something observant and lurking about the photographer’s perspective. In another photograph, the soldiers of the battalion can be seen during a drill. The violent, white gaze predominant in the archive’s materials is obvious. The artist therefore approaches them in a broken form and transforms them through her own artistic imagination. In the three works in the exhibition that are based on the archive, Uambembe focuses on individual sections of these photographs. She has enlarged them so much that they are only blurred and one can only guess what was originally intended to be observed. By blurring and narrowing them, she takes away part of the field of vision of the observing and lurking white gaze. She adds a further element of opacity by painting over the photographs with colored and charcoal pencils and acrylic paint. In this act of appropriation, images are created that tell of life around the Okavango River from the artist’s perspective.

An installation consisting of bricks and buckets filled with water deals with the coexistence of today’s Okavango residents with the river and its animal inhabitants. Many of the settlements along the Okavango have no access to drinking water, which is why the residents usually use plastic buckets to draw water from the river for their daily needs. This is a very direct interaction with the water, but especially in times of high water, problems arise from the fact that crocodiles come very close to the edge of the river and attack people. Traditionally, crocodile attacks were prevented by erecting dams and barriers made of bushes. This shows a different form of interaction with nature, water and the earth than we are used to. In the gallery space, the installation with the buckets thus also stands for the search for forms of coexistence with the crocodiles, i.e. for other, pacified human-nature relationships.

However, the fact that the Okavango marks a border for more than 400 kilometers is rooted in the history of German and Portuguese colonialism. It was these two empires that defined the river as the border between the two colonial territories in December 1886. The local Kavango population had always settled on both sides of the river. The history of Uambembe’s own family and that of German colonialism are thus intertwined in the Okavango. In a video work, the artist creates a link between her family’s former place of residence and the enclosed waters of her new home in Berlin. For Helena Uambembe, the video created on the Landwehr Canal becomes a ritual of transition and passage.

Julian Volz