Luca Ilic

Luca Ilic at Shore Gallery

Advertisement

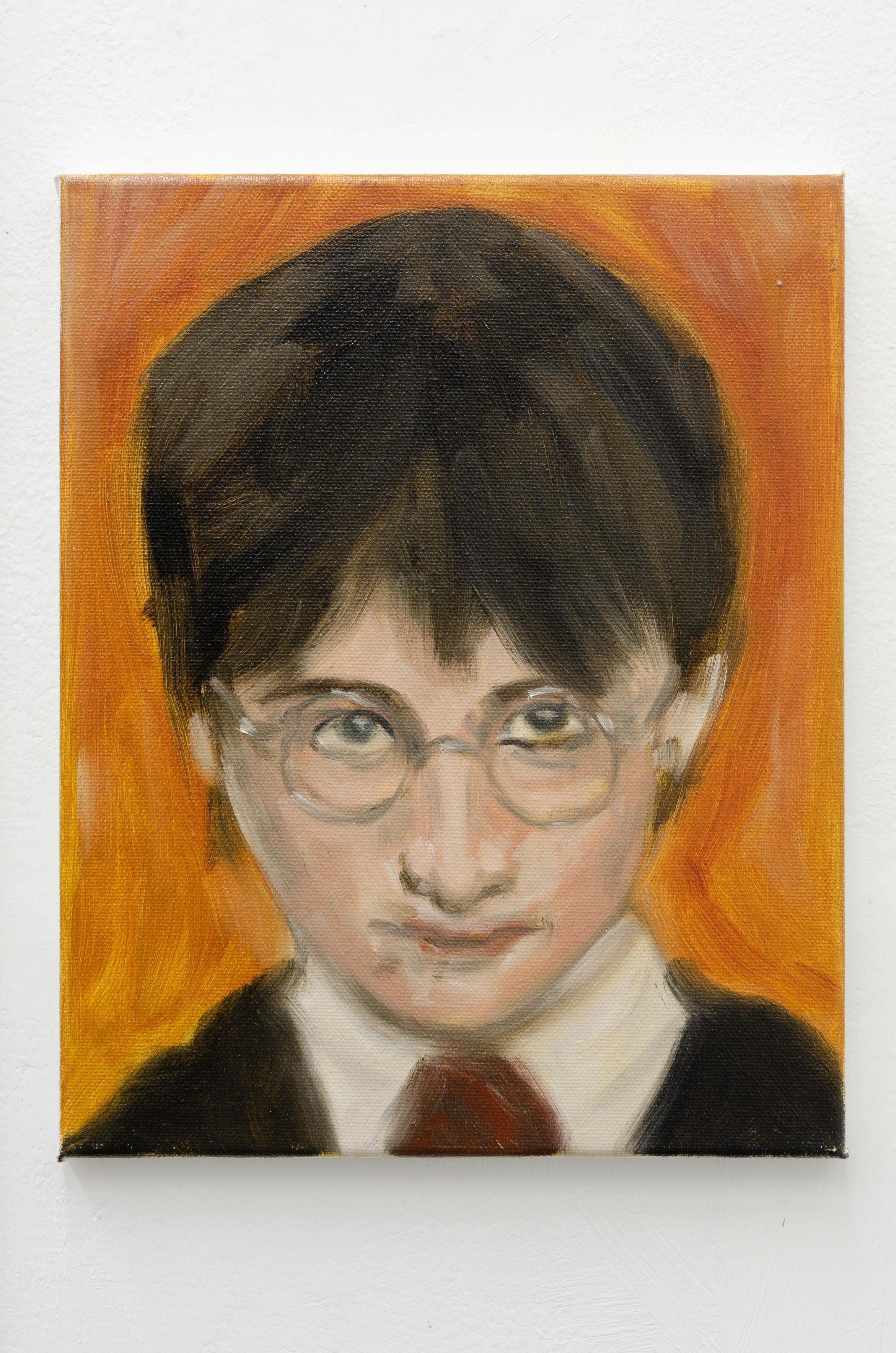

Luca Ilic, Harry said nothing. He felt a bit awkward. Stored in an underground vault at Gringotts in London was a small fortune that his parents had left him., 2024, Oil on canvas, 50cm x 70cm

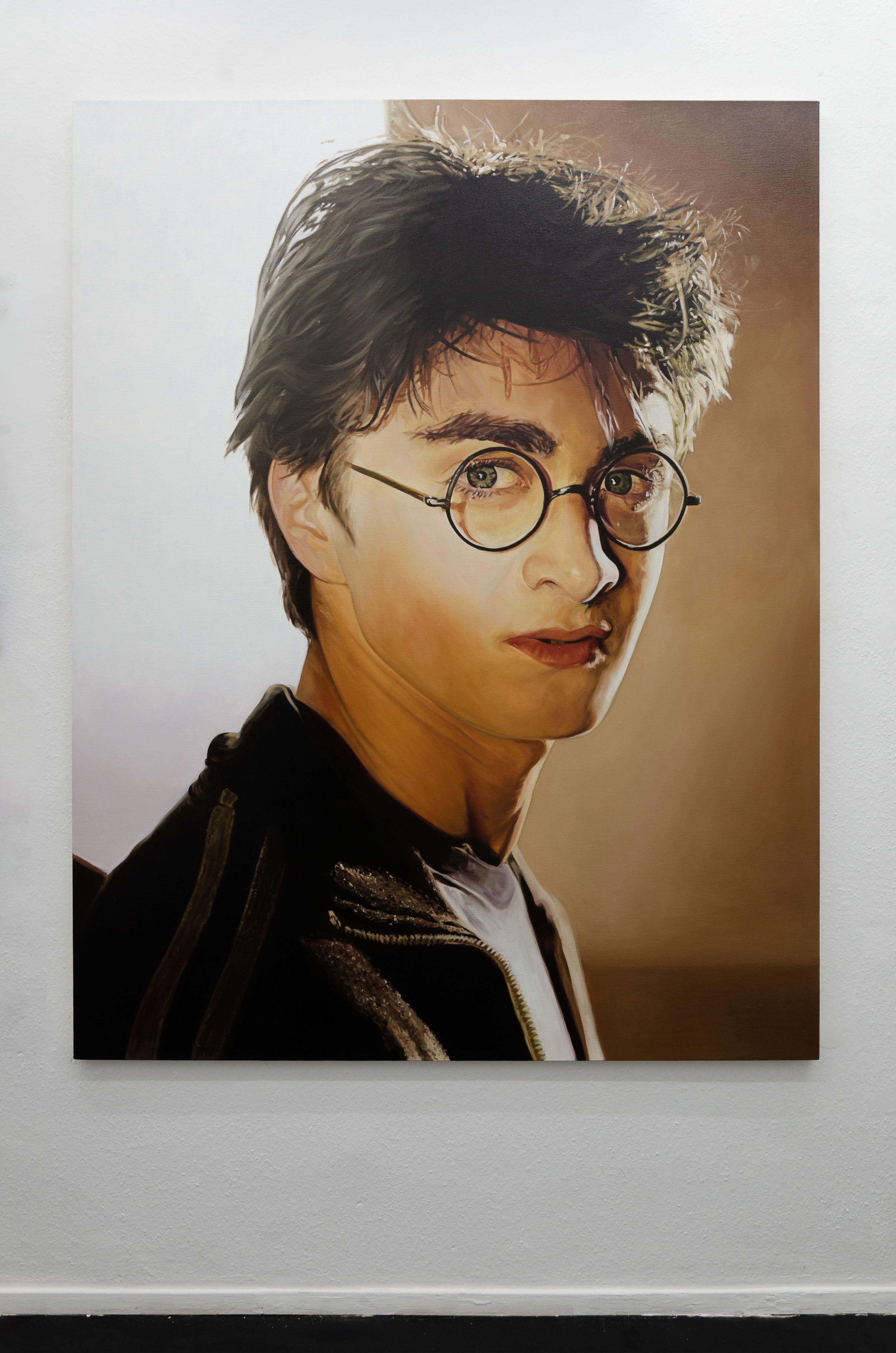

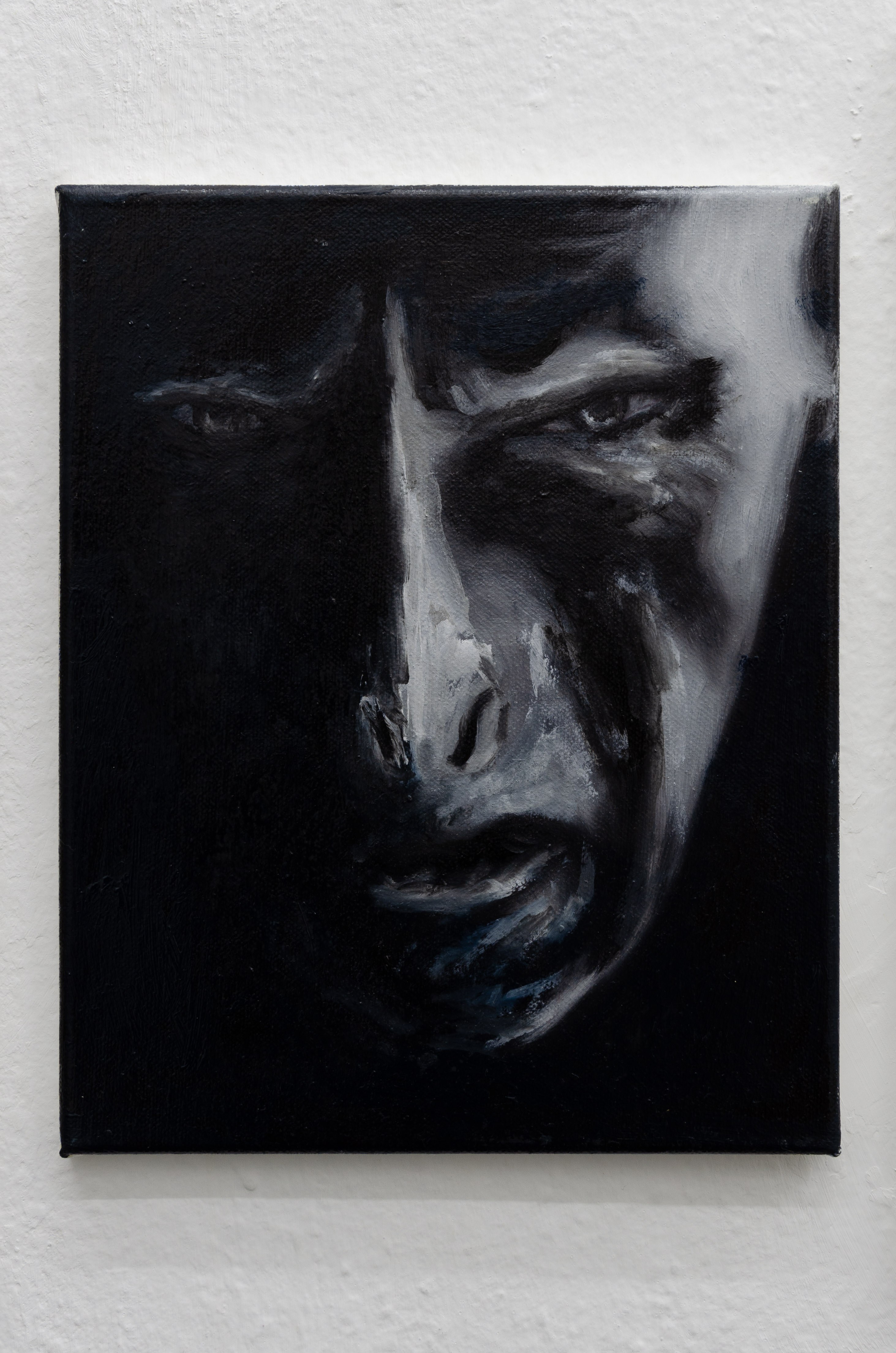

Luca Ilic, Someone had poked Ron in the back of the head. It was Malfoy. ‘Oh, sorry, Weasley, didn’t see you there.’, 2023, Oil on Canvas, 180cm x 140cm

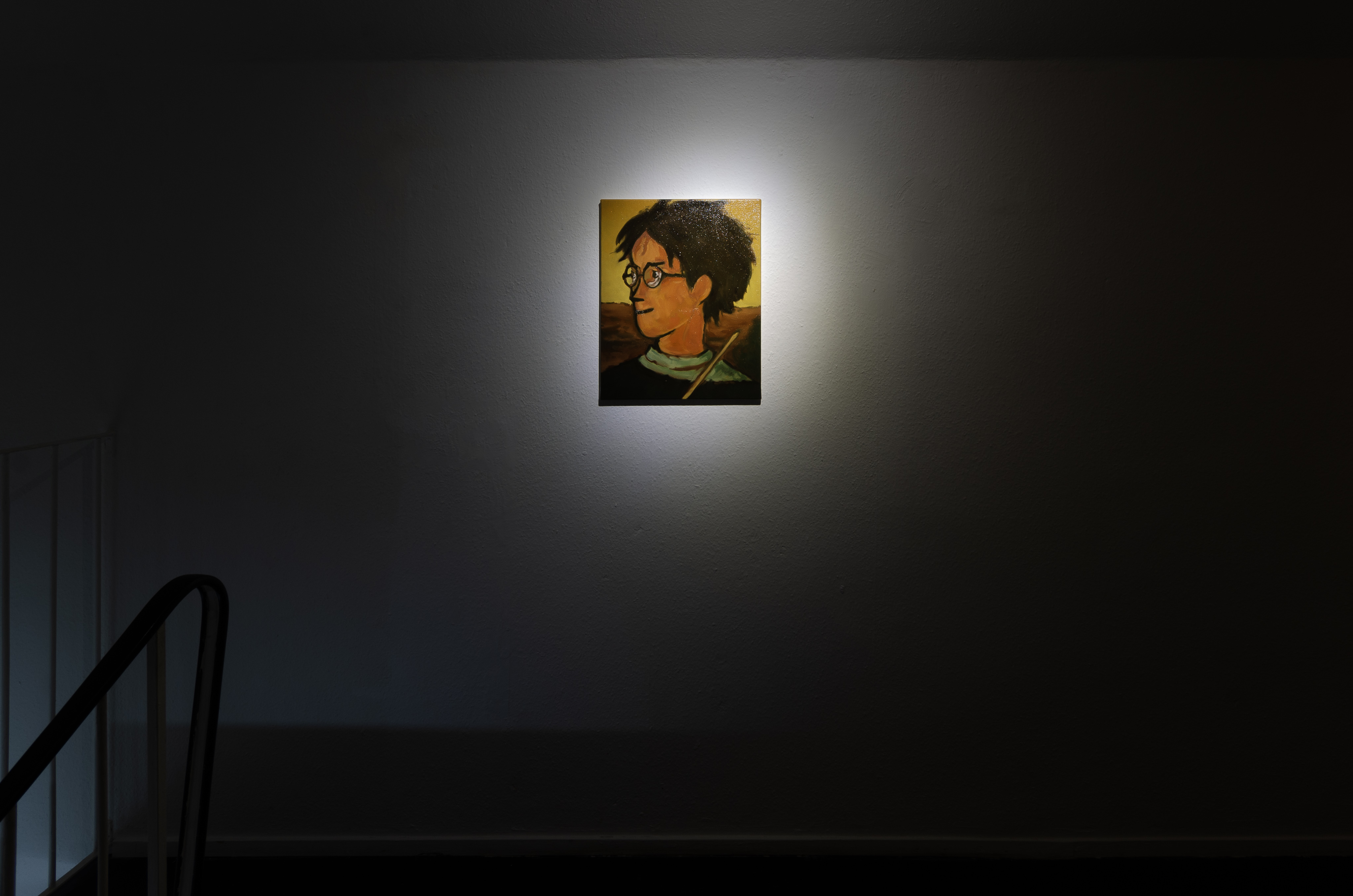

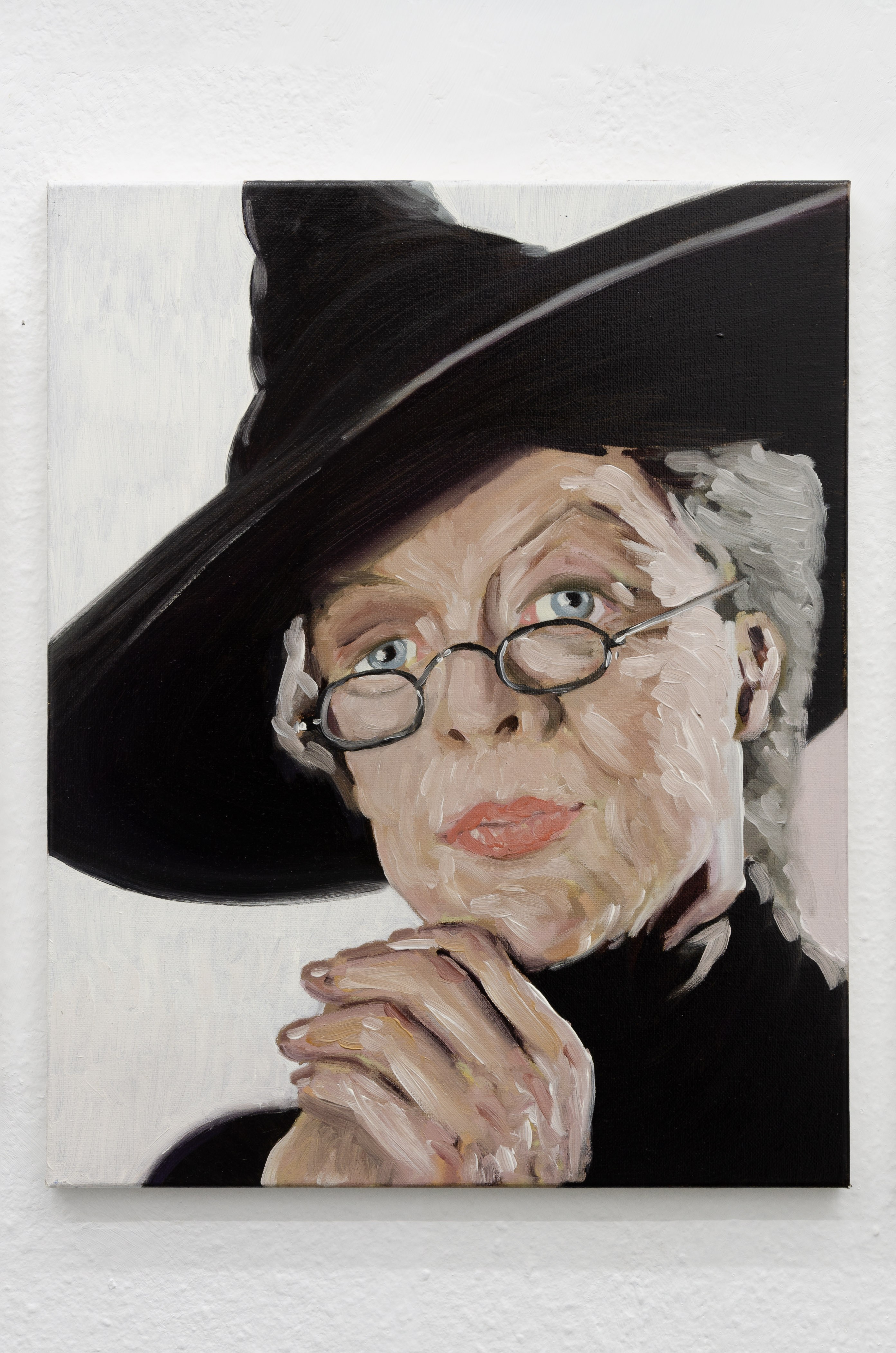

Luca Ilic, ‘Who’s there?’ he shouted. ‘I warn you – I’m armed!’, 2021, Oil on canvas, 30cm x 24cm

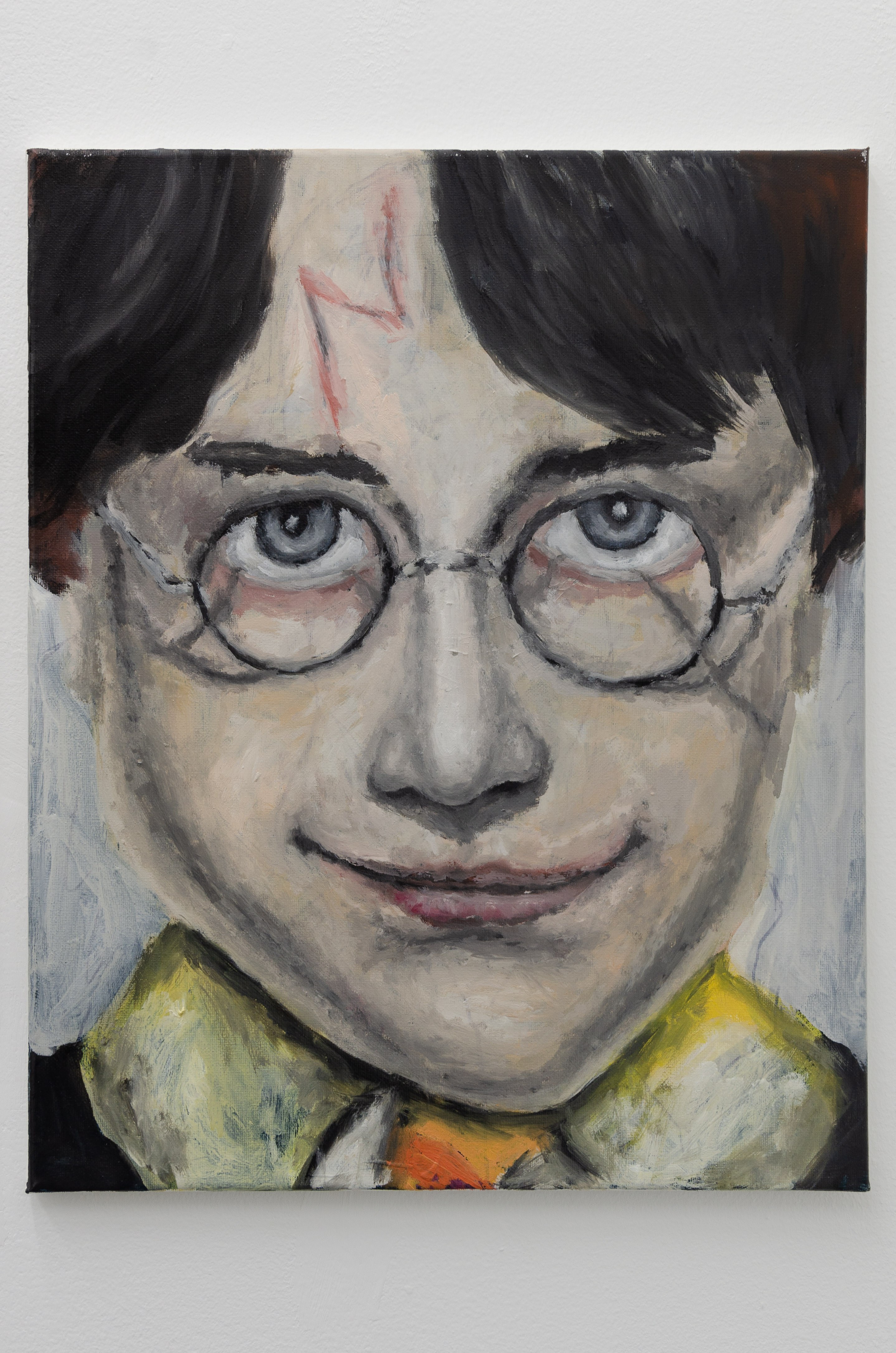

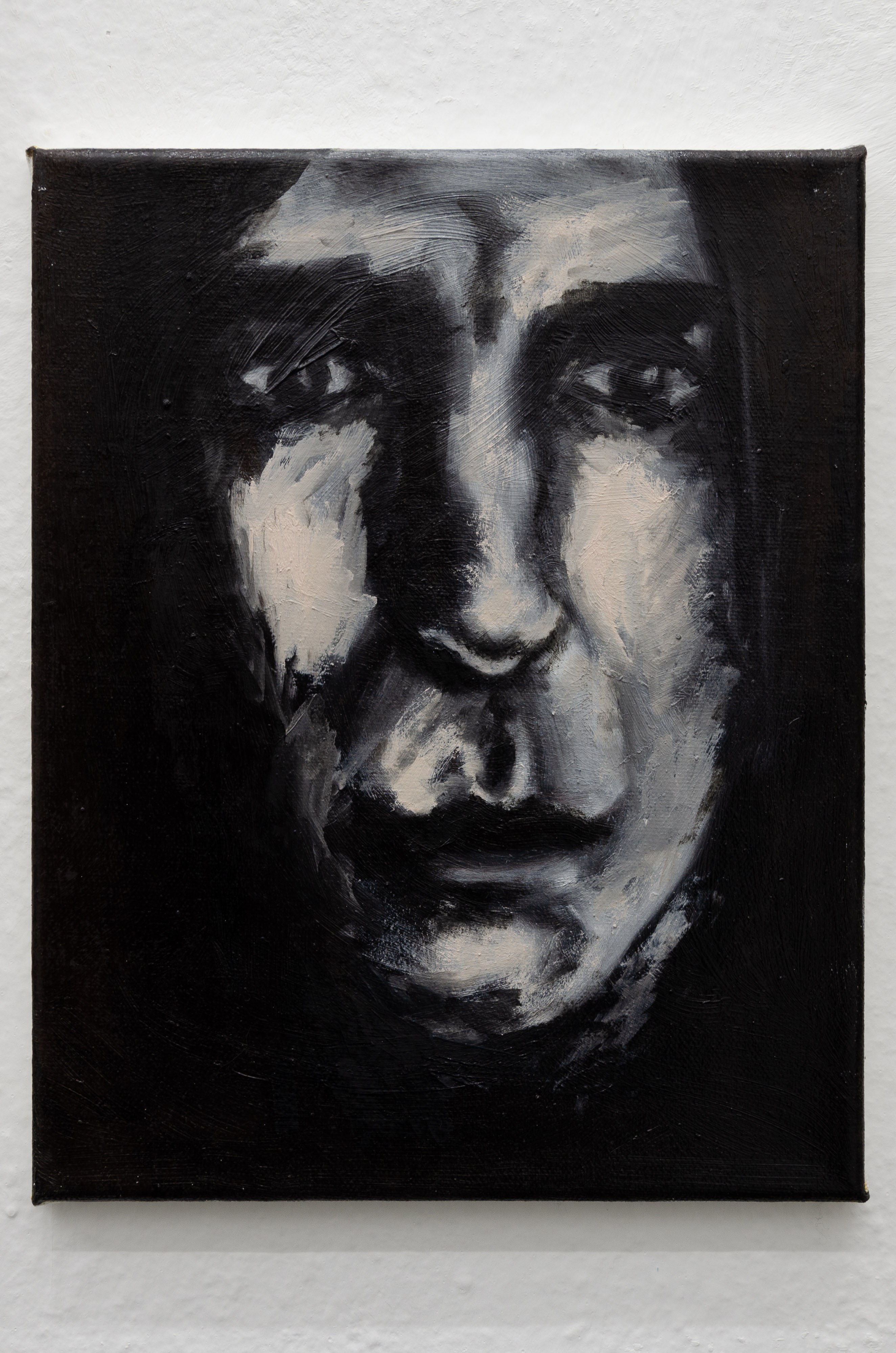

Luca Ilic, Harry Potter was a wizard - a wizard fresh from his first year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry., 2024, Oil on canvas, 50cm x 40cm

Luca Ilic, ‘Don’t tell me what I can and can’t do, Potter., 2022, Oil on canvas, 30cm x 24cm

Luca Ilic, Uncle Vernon might still have been able to make his deal - if it hadn’t been for the owl., 2024, Oil on canvas, 40cm x 50cm

Luca Ilic, ‘Don’t you call me an idiot!’ said Neville. ‘I don’t think you should be breaking any more rules! ’, 2024, Oil on canvas, 30cm x 24cm

Luca Ilic, ‘Years an’ years ago,’ said Hagrid., 2022, Oil on Canvas, 50cm x 40cm

Luca Ilic, ”He’s back!” said George. “Dad’s home!”, 2024, Oil on canvas, 30cm x 24cm

Luca Ilic, ‘You knew?’ said Harry. ‘You knew I’m a – a wizard?’, 2021, Oil on canvas, 40cm x 30cm

I grew up knowing that I was a Hufflepuff. It was a certainty that was confirmed again and again - first in the schoolyard, then later at parties and even later as small talk conversation. It was clear that this (self-)attribution was a deficiency. I only learned later that harmlessness, i.e. Hufflepuff-ness, is also a secret weapon (or a magic trick).

Harry Potter is a language of its own, a symbolic system that can be used in almost any social constellation. One person is usually Slytherin, one Gryffindor, one Ravenclaw and one party at the table, like me, has to fulfill the role of the Hufflepuffs.

This distribution of roles is somewhat binding. The Harry Potter universe or etymological system is an omnipresent reference that has a religious connotation. Almost everyone knows what it means to be a Hufflepuff; it is much more specific than, for example, knowing the characteristics of one’s own star sign.

Specific expressions, spells, objects and tools have also entered our everyday use. Arch-enemies become “He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named”, Avada Kedavra remains an unpronounceable phrase, track 9 3/4 a standing term for bureaucratic opacity and only recently a friend described his untidy bedroom as a chamber of secrets. The fictional standard work “Great Wizards of the Twentieth Century, or Notable Magical Names of Our Time” is one of the more relevant encyclopaedias of our time - precisely because of its quality of being fictional.

The Harry Potter reference system is therefore generation-defining for millennials - it has become deeply inscribed in the collective memory of our slightly dysfunctional generation. We are stuck between the analog and the digital, between the discourses, the ideas of normativity and the relationship to economic ambition. Diving into the fictional is a rewarding escape. It is particularly obvious - many of us learned to read with and through the world of Harry Potter.

When the Harry Potter movies came out, it was almost like breaking the religious ban on representation. The images that had previously existed in our childhood minds (and those of our enthusiastically reading parents) suddenly literally took on a human face. The individual representations, incomparable because they could not be expressed through language, were standardized.

In the drawings of primary school children in their early 2000s, you can see how the fantasy face with the scar on the forehead suddenly becomes that of child star Daniel Radcliffe, who - knowing Macaulay Culkin’s fate - was worried about rather than impressed by his success right from the start. The idea of fan-dom, star-dom and hobby art also seems to be stuck in the early 2000s.

Luca Ilic’s work operates within this aesthetic system. And it is not exactly clear whether the invisible author takes on the role of the fan, the star or the (hobby) artist. His position, in its pretended naivety, also seems to be a kind of “secret weapon”. A magic spell that plays directly with our collective memory and the knowledge of the redundancy of remembering. With the quality of scraps of memory to haunt us unconsciously and to repeat themselves over and over again.

It is hard to believe that his works want nothing more than to reproduce what we already know all too well. The categories of craftsmanship and dilettantism, of original and copy disappear completely. The works are as direct as they are complex - as if they profess a two-dimensionality that disguises and thereby creates a depth, a multi-layeredness.

Luca Ilic’s constantly self-perpetuating (that is, magically progressing) series are the religious icons of the early 2000s. They remind us, sometimes unpleasantly, but always with a fascination (in which one feels caught), of how much we are all, whether we like it or not, followers of this shameful pop-cultural religion called Harry Potter.

The specific aesthetic is as important here as its quality of having something generic about it. Spells, for example, in their redundancy, do have a correlation with prayer or curses, and not by chance. Luca Ilic’s works, especially in their paint-by-numbers-like appearance, do just that: they put a spell on us.

They mystify themselves in their unashamedly direct access to the early childhood, to the hidden, the forgotten and the affective. They remind us of our secret wish that the letter would finally be in the letterbox and that we would all get an owl as a pet. And of our fear that the talking hat would declaim loudly that we were a Hufflepuff.

But who is Luca Ilic? What role does this secret author play, who disappears behind the reference as much as he is omnipresent in his invisibility or undiscoveredness. He is just as mystically charged a string-puller as „He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named”. Or at least “A Great Wizard of the Twentieth Century, or a Notable Magical Name of Our Time”. Just as we would all like to be.

Olga Hohmann