Fanny Varjo

Lore garden

Advertisement

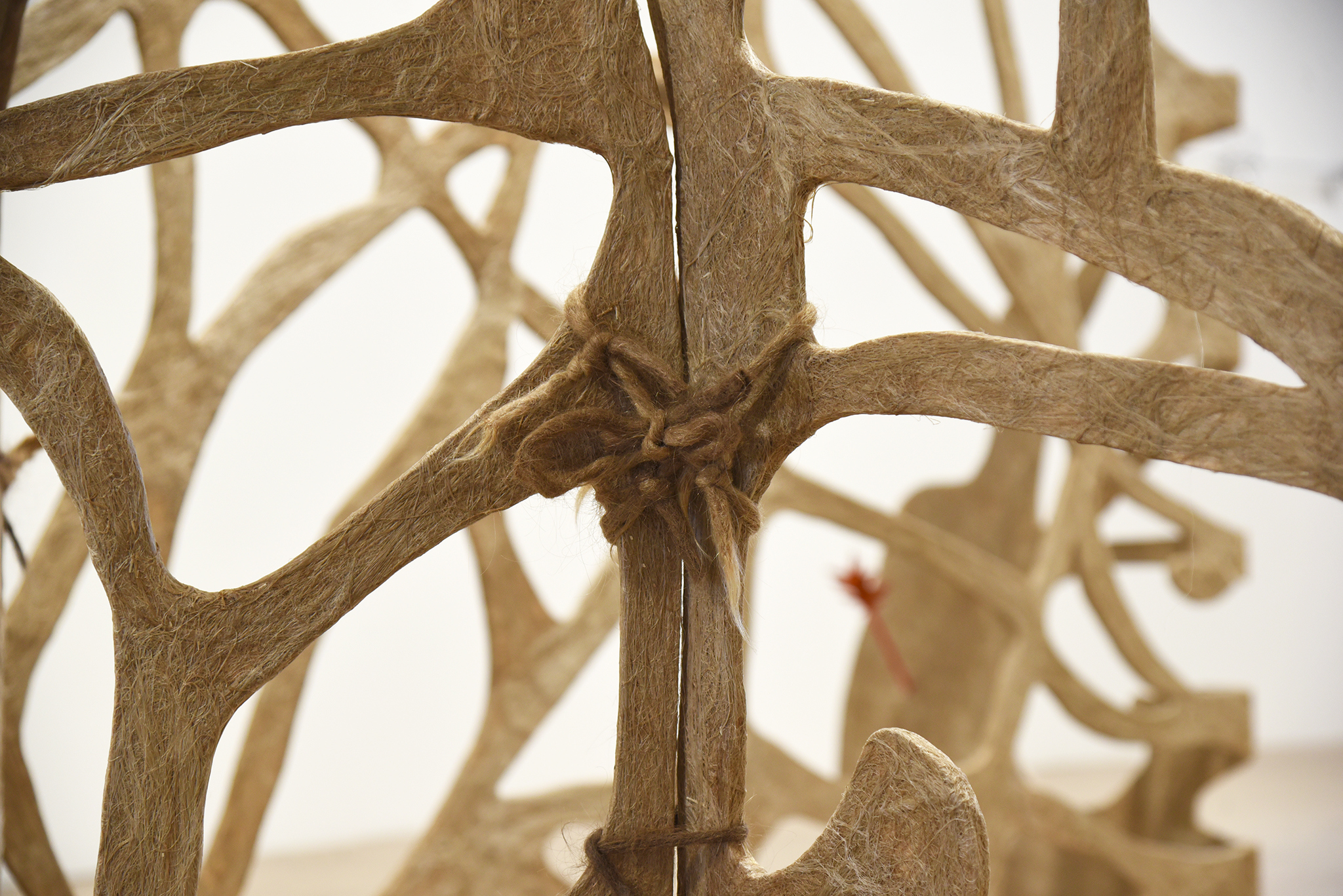

Lore Garden – on myths and the history of poisons

The doctor and alchemist Paracelsus (1493–1541) wrote in 1564: “What is there that is not poison? All things are poison, and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison”. (Honburg & Vaupel 2019, 6.) This enduring quote perhaps reveals something essential about the nature of poisons, albeit reflecting the understanding of its time. The health-promoting as well as destructive potential uses of poisons have fascinated and frightened people throughout the ages. The mystique of poisons has inspired stories and myths, recurring in culture from literature to plays. The world of poisons has provided remedies for many ailments and, on the darker side of history, technologies for warfare, assassinations, and executions. The ideas for the works in this exhibition arise from historical stories related to poisons and particularly poisonous plants. This text sheds light on these stories and explores the history of poisons. Through the text, you will learn, among other things, how a rooster was related to Socrates' death, where medieval people found unicorn horns, and how the poisonous plant mandrake and a dog's tail were connected to each other.

The concepts of poison and medicine have been intertwined in Western tradition since the time of Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) (Cunningham 2018, 1). The ancient Greek terms pharmakon (poison) and toxon (arrow), as well as the Latin venenum, virus and potio all referred to poison, eventually influencing the English word poison and the French word venin (Honburg & Vaupel 2019, 5). An important dimension of the ancient concept of poison is that it referred both to “good poison”, meaning medicine, and “bad poison”, meaning magical substances like poisons and magical potions intended to harm or even cause death (Honburg & Vaupel 2019, 5). Before the development of modern medicine, natural medicinal herbs and potions made from them were central to disease treatment. Naturally occurring poisons were also used as antidotes, for example in treating poisonous snake bites (Cunningham 2018, 2). Alongside modern medicine, traditional medical and healing systems still operate in various cultures, using different natural medicines instead of modern pharmaceuticals. Perhaps the best-known of these systems are Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda from India.

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, various magical objects that were believed to heal and protect against poisons gained popularity. These included gemstones, minerals, and animal parts such as horns and teeth. A highly valued item among the upper class was a drinking horn made from horn of narwhal (Monodon monoceros) but was believed for belonging to unicorn. (Lavers 2017, 101.) This drinking horn was thought not only to promote health but also to protect against poisons, as the goblet made from a “unicorn horn” was believed to have protective properties. In contrast, the lower classes had to settle for powder ground from the horn. (Lavers 2017, 102.) Although the origin of the unicorn horn was already questioned at its own time, the trade still remained lively, weakening only in the 18th century (Lavers 2017, 102).

A poisonous plant might have lurked in the nearby environment or, when ending up in the wrong place, might have caused fatal accidents, especially endangering children and domestic animals. The highly poisonous hemlock (Conium maculatum), also found in Finland, is one such plant. A well-known historical poisoning case involving hemlock concerns the story of the dead of ancient philosopher Socrates. Socrates (470–399 BCE) was active in Athens, Greece and was known for his unconventional thoughts. Socrates was eventually sentenced to death by poisoning because he did not respect traditional gods and was feared to corrupt the minds of the youth with his ideas. In Plato's dialogue Phaedo, Socrates is reported to have said as his last words to his follower Crito that he owed a rooster to Asclepius and urged him to pay this debt. (Nagy 2015, 3.) According to the story, the poison used to execute Socrates was made from hemlock (Nagy 2015, 3). Sacrificing to the ancient god Asclepius was thought to save one from illness in ancient Greece (Nagy 2015, 3). The fascination with mythical stories partly arises from their openness to interpretation, stimulating the imagination. The story of Socrates' last words has produced numerous interpretations over time.

There are widespread myths associated with plants considered dangerous, such as the mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) and henbane (Hyoscyamus niger). During the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, the mandrake or mandragora was popular because of its supposedly protective properties and carrying the plant as an amulet was believed to protect its bearer from misfortune and illness (Rowlands 2018, 80). Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) on the other hand was particularly associated with witches, and in these myths, witches were believed to use ointments made from the plant to gain the ability to fly (Alanko et al. 1982). According to the myth associated with the mandrake the plant's root screams when pulled from the ground. The story goes that a person had to protect themselves from the scream by tying a rope to a dog's tail and the other end to the plant and the dog would pull the root out of the ground, thus avoiding exposure to the deafening scream. The origin of this geographically widespread myth has been later traced particularly to the Middle East. (Dafni et al. 2021.) The popularity of the mandrake is reflected in the fact that the plant has as many as 292 different names in 41 different languages (Dafni et al. 2021).

As the culture of healing changed, natural healers were marginalized in society. Outside the mainstream, healer’s activities aroused suspicion, especially during the witch hunts which again fueled myths and stories. On the other hand, stories about the magical properties of poisonous plants and unicorn horns were popular in their own time, thereby stimulating trade. The spread of stories related to poisons and poisonous plants not only highlights the power of stories but also underscores their role in the history and the long tradition of natural healing.

Dafni, A., Blanché, C., Khatib, S. A., Petanidou, T., Aytaç, B., Pacini, E., ... & Benítez, G. (2021). In search of traces of the mandrake myth: the historical, and ethnobotanical roots of its vernacular names. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 17, 1-35.

Huovinen, M.-L., Kanerva, K. & Alanko, P. (1982) Suomen terveyskasvit: luonnon parantavat yrtit ja niiden salaisuudet. Toim. Huovinen, M-L., Kanerva, K., Alanko, P. Valitut palat.

Grell, O. P., Cunningham, A., & Arrizabalaga, J. (Eds.). (2018). It All Depends on the Dose: Poisons and Medicines in European History. Routledge.

Honburg, E. & Vaupel, E. (2019) Hazardous Chemicals: Agents of risk and change, 1800–2000. (Ed.) Ernst Honburg & Elizabeth Vaupel. Berghahn.

Nagy, G. (2015). The Vow of Socrates. Classical Inquiries. Harvard library.

Lavers, C. (2017) Origins of Myths Related to Curative, Antidotal and Other Medicinal Properties of Animal “Horns” in the Middle Ages. In Wexler, P. (Ed.) Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Academic Press.

Rowlands, A. (2018) Witchcraft narratives in Germany: Rothenburg, 1561-1652. Manchester University Press.

Vivi Varjo