Wolfgang Betke

Candide's Garden

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Advertisement

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Installation view, Wolfgang Betke, Candide's Garden, SETAREH, Berlin © Trevor Good

Wolfgang Betke, Hermit's delight, 2019-2024, Painted canvas, 240 x 200 cm

Wolfgang Betke, Muriburiland, 2023, Oil, ink, spray paint on aluminium

Wolfgang Betke, Die beste aller möglichen Welten, 2024, Painted aluminium, 270 x 250 cm

Wolfgang Betke, Das wird schon/That will be fine, 2024, Painted aluminium, 270 x 375 cm

Wolfgang Betke, Optimist, 2024, Paint on folded aluminium, 100 x 80 cm

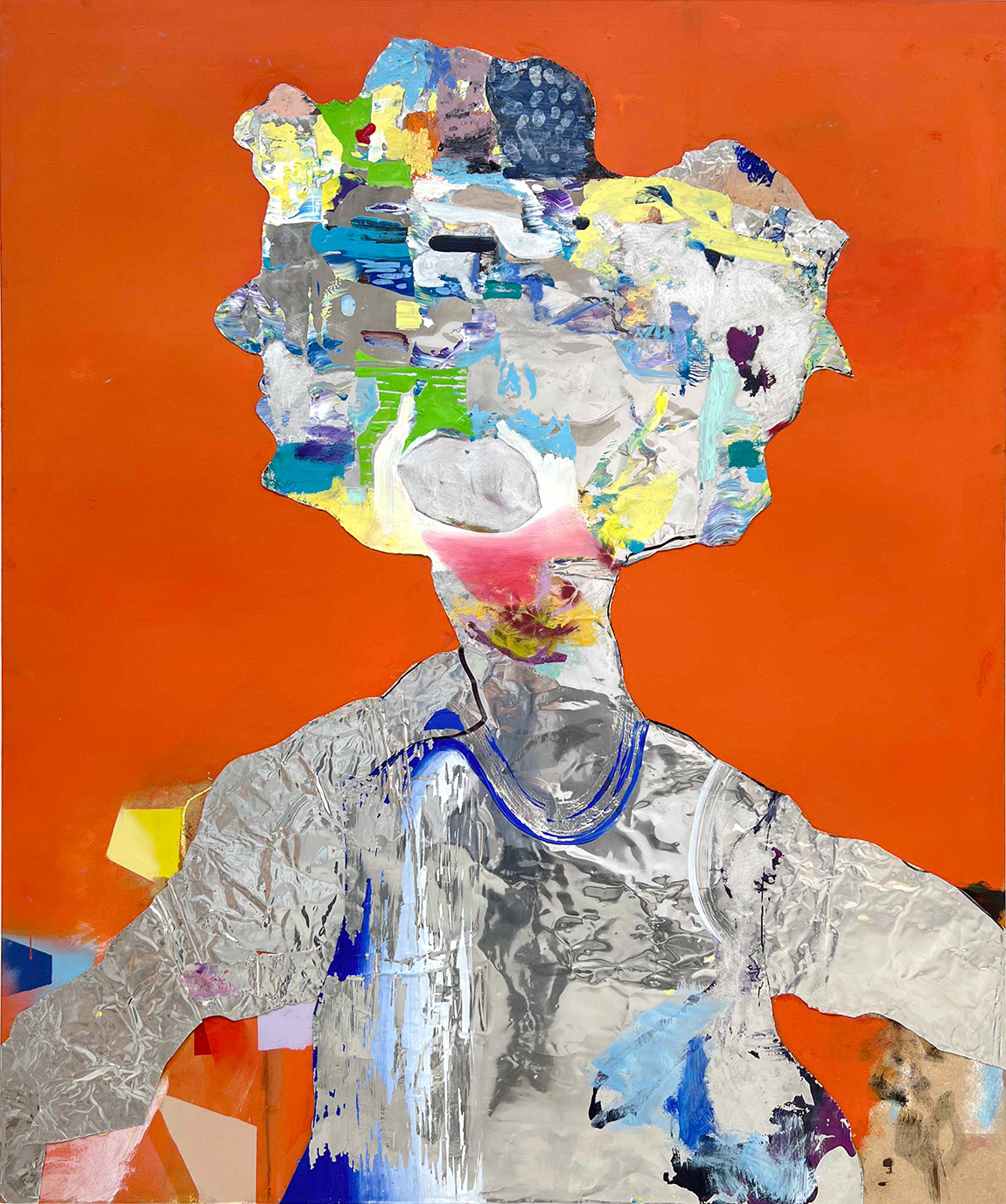

Wolfgang Betke, The Gardener, 2024, Cut out aluminium collage on MDF, acrylic and oil paint

Wolfgang Betke, Abwehrzauber, 2020-2024, Ink, acrylic, oil on aluminium, 149.3 x 125 cm

Wolfgang Betke, Entsetzen und Gelassenheit, 2024, Oil, acrylic, spray paint on canvas

Wolfgang Betke‘s vibrant paintings and sculpture foreground the conditions and processes of creation through the medium of paint; the lengthly application and removal of paint on the canvas becomes a cipher to reveal the duration of its genesis. Betke describes these painted objects as traces of a pronounced ‘bodily automatism’. This neologism is a continuation of the surrealist terms ‘lyrical automatism’ or ‘psychic automatism’.

The exhibition Candide’s Garden derives its title from the final lines of Voltaire‘s novel, where after a horrendous sequences of events the hero takes advice from a valiant old man who explains that everybody should tend to their own garden. This seemingly idealistic platitude is in response to the optimism which Voltaire sought to critique in the writing of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a thinker who believed that since this is the only apparent world that it must be the best of all possible worlds. This phrase is taken up sarcastically through out the book to illuminate that politics, religion, and social hierarchies are all human constructions and not entirely ‘God’s will’. Betke takes this notion up as reflective of his own artistic research.

In drawing from the memory of the body, his process is a contemplative one and regularly engages a world of speculative thought based on intensive examination of philosophical questions. ‘Initially, my painting is not a language, but a pure material setting. Material traces of bodily gestures only become language when they are associatively charged with meaning or turn into the figurative. In my paintings, we watch language emerge.’ And so, realising incredibly rich fields of colourful and imaginative mark making, which immerse the viewer in their sensuous depths, is but one aspect of Wolfgang Betke’s art. For him, the work is as much dedication to the process of thinking through this creative activity as much as it is a deeply aesthetic form of production. Influenced by his own philosophically rich world view, which engages the ancient and the contemporary in equal measure, he works to express these contemplations through the act of making pictures. Yet to call them pictures is to undo the complexly layered results of his process. In fact the works achievement may be the building up and undoing of images, the artist both plotting experiences and obfuscating their delineations, realising them as densely felt temporalities. Like Voltaire, he holds up both shadow and light to reveal the entropic conditions of Modernism.

Betke’s pictures celebrate the beauty of life even amongst the detritus of our ravaged landscape. We see figures in the work, silhouettes appearing and dissolving, cities rising only to crumble. We catch glimpses of art historical resonances, the past repeating in the present, lessons to be remembered. But the magic of this process is that we may learn from these paintings to hope. Not the received optimism of Leibniz, but to plot our own path through consequence and find the inner enchantment of realising our own garden.