Groupshow

Yellow brick, blue brick, perpetually

Project Info

- 💙 B32 Artspace

- 💚 Sjoerd Beijers

- 🖤 Groupshow

- 💜 Sjoerd Beijers

- 💛 Johan Poezevara

Share on

Exhibition view Yellow brick, blue brick, perpetually, 2024, B32 Artspace, Maastricht

Advertisement

Samuel White, revolving door, night turbulance, 2024. Various paper, found wood, charcoal, biro, oil pastel

Helena, The Great Misunderstanding, 2024. Wax, dirt of the neighbourhood. Mounir Eddib, untitled, 2024. Lead, photo negative

Samuel White, air path, 2024. Various paper, found wood, charcoal, biro, oil pastel

Found spiders, 2024

Helena, The Great Misunderstanding, 2024. Wax, dirt of the neighbourhood

Mounir Eddib, untitled, 2024. Lead, tar, rope

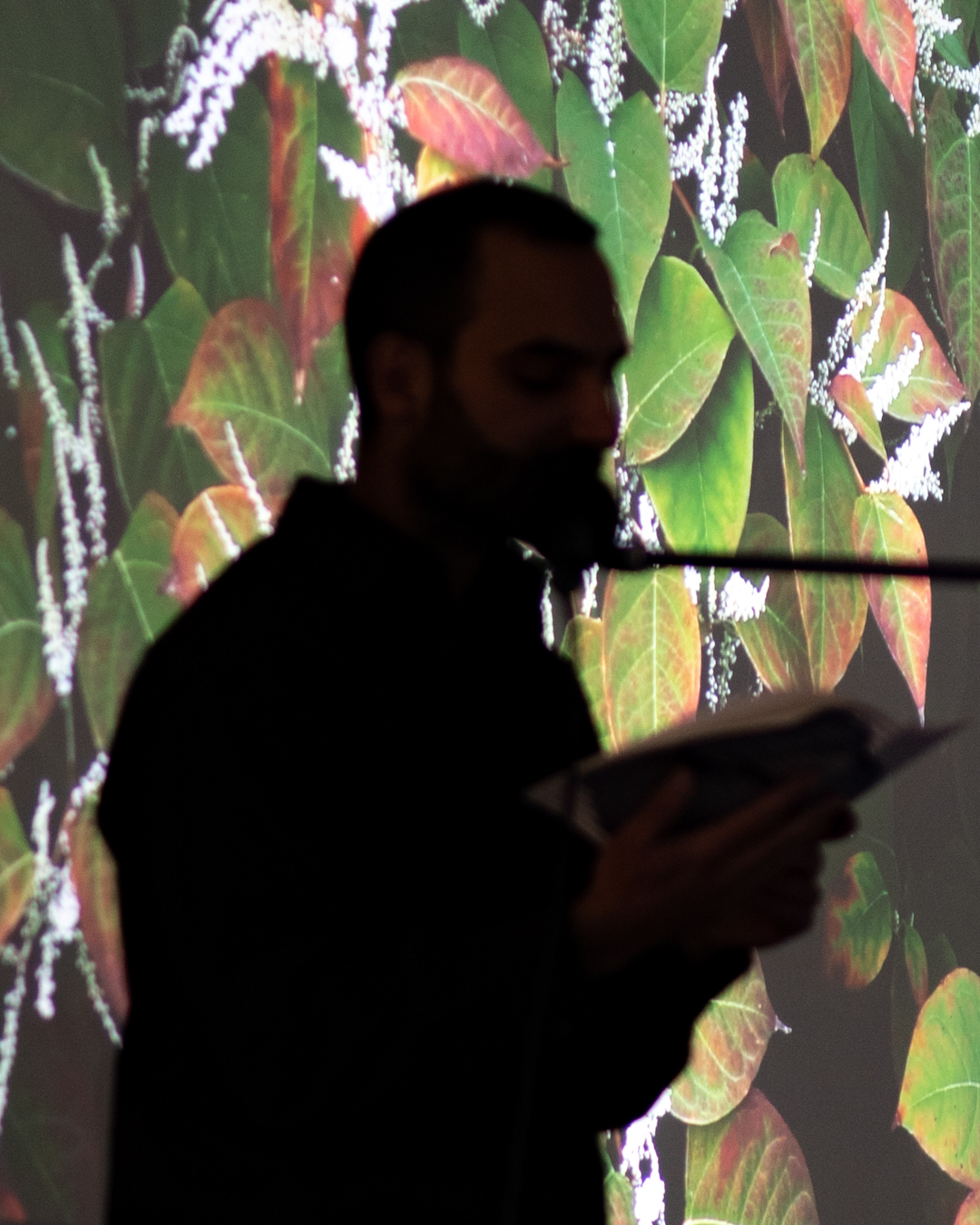

Alaa Abu Asad, In the absence of the invasive: Can we finally look at the Japanese knotweed as a green future companion?. 2024. performative reading

Alaa Abu Asad, In the absence of the invasive: Can we finally look at the Japanese knotweed as a green future companion?. 2024. Japanese Knotweed tea

Helena, The Great Misunderstanding, 2024. Wax, dirt of the neighbourhood

Helena, The Great Misunderstanding, 2024. Screen, surveillance camera, radio transmission

Exhibition view Yellow brick, blue brick, perpetually, 2024, B32 Artspace, Maastricht

Angelina Nonaj, How can we live together?. 2024, Empty glasses, vinyl text, fabric, collective drawing, canvas

Angelina Nonaj, How can we live together?. 2024, convivial lunch and workshop

Angelina Nonaj, How can we live together?. 2024, convivial lunch and workshop

Mounir Eddib, untitled. 2024, Oil paint derived from Winterslagse brick, tar and lead on canvas

Alaa Abu Asad, In the absence of the invasive: Can we finally look at the Japanese knotweed as a green future companion?. 2024. Booklet, dried Japanese Knotweed sticks

Exhibition view Yellow brick, blue brick, perpetually, 2024, B32 Artspace, Maastricht

The residential neighbourhood of De Ravelijn finished its construction in the fifties. It originated as a “woonschool,’ or dwelling school, a district with the goal to re-educate those that were deemed to be antisocial. As lines drawn on paper became roads, pavements and houses, different blocks were split up into A, B, C and D. The last category was meant for larger families, while B and C houses were reserved for people deemed most antisocial. The A category accommodated inhabitants with the greatest chance of reintegration, and were therefore located closest to the inner city.

This correspondence between the letters A, B, C and D, and perceived social status is a clear example of how acts of division and measurement not only organise space, but also inform ways of living. This logic is reflected in De Ravelijn’s urban planning. The homes are arranged along a horseshoe-shaped street, encouraging self-surveillance. At the heart of the neighbourhood sits the former community centre of the woonschool, now B32. Numerous activities were organised to instil a sense of community and to focus on cultural and religious education. By means of activities and house visits the woonschool taught the residents how to live properly, focusing on domestic habits, marriage, the wife’s housework, the husband’s work ethic, and child-rearing.

The organisation of space as a tool for behaviour control is a well-established practice. We see that the first enclosures of land in England are historically tied to the witch-hunts. Those not conforming to the values of patriarchy and economic profitability were burned at the stake. Thus the logic of measurement, which divides a whole into serial units to be (re)combined at will, does not only reduce once vital land into exploitable patch; It also instils a view that everything, and anyone, can be categorised, measured and exploited in favour of capitalist success. “Yellow brick, blue brick, perpetually” is an inquiry into these mechanisms. How do these permeate different facets of society, and—in often invisible manners—shape our lives? As such, the exhibition connects the specific context of De Ravelijn to a broader idea of enclosure—not just of land, but also of knowledge, bodies, our relationship towards nature and one another.

The invited artists respond to these themes in various manners. Samuel White uses unconventional measurement units, such as footsteps, iPhones, and even trousers, to explore the architectural space through a series of drawings. This playful approach to measurements and scale forms the foundation of their investigation into how we experience and perceive constructed environments. Helena intervenes with a flock of wax-cast pigeons, placed at intervals on ventilation ducts, inhabiting cages, and scattered throughout the building. This discarded companion species becomes a lens through which she questions how we share space, examining how power relations mediate our movement through both urban and exhibition spaces. Mounir Eddib uses materials prevalent in the decommissioned mining sites of Genk to bring marginalised stories to the centre, while forging connections with the Moroccan diaspora. These materials, once tied to industrialisation, are repurposed to bring alternative knowledges to light. He explores intimate relationships to the land through folk ritual practices—understandings which run against the modern logic of measurement and extraction.

On October 26th the public programme unfolded. Alaa Abu Asad presented a performative reading, based on his research with invasive plant species. He investigates the language used to define which plants are “wanted” and which are “invasive,” questioning how language structures shape the perception of what, or who, is considered a rightful inhabitant of an environment. Assuming the role of the troublemaker, Angelina Nonaj created an environment that invites dialogue with the local community and other visitors. They prepared a workshop and lunch for the public programme, during which a set of language-based games and scores sought to stimulate unlearning, and collective reflection on ideas of community and conviviality. In the past, the ‘woonschool’ of De Ravelijn claimed to educate individuals to become good citizens. Today, the artists activate this historical site as a space for unlearning the imposed structures, to question the politics of space and to mend the connections severed by enclosure.

Sjoerd Beijers