Michael E. Smith

Michael E. Smith invited by Cédric Fauq

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Glove, wire, 194 × 15 × 18 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Advertisement

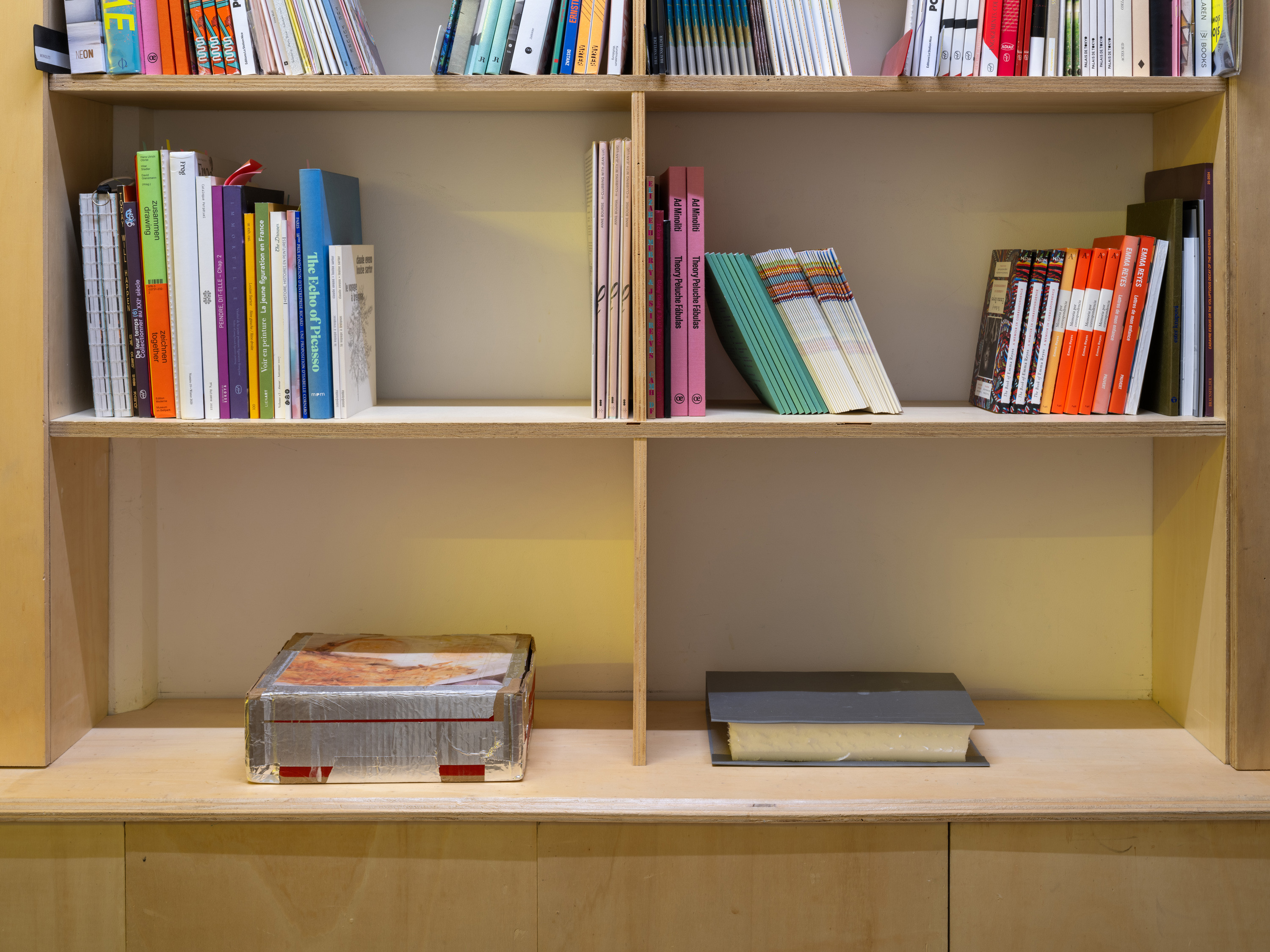

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Fleece, tv stand, 84 × 80 × 52 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Masks, led lights, 86 × 37 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Peas, 2025, Basketballs, foam, 64 × 23 × 23 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Fabric, plastic, 274 × 177 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Gift, 80 × 55 × 41 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Print, cardboard box, fossils, 31 × 24 × 11 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

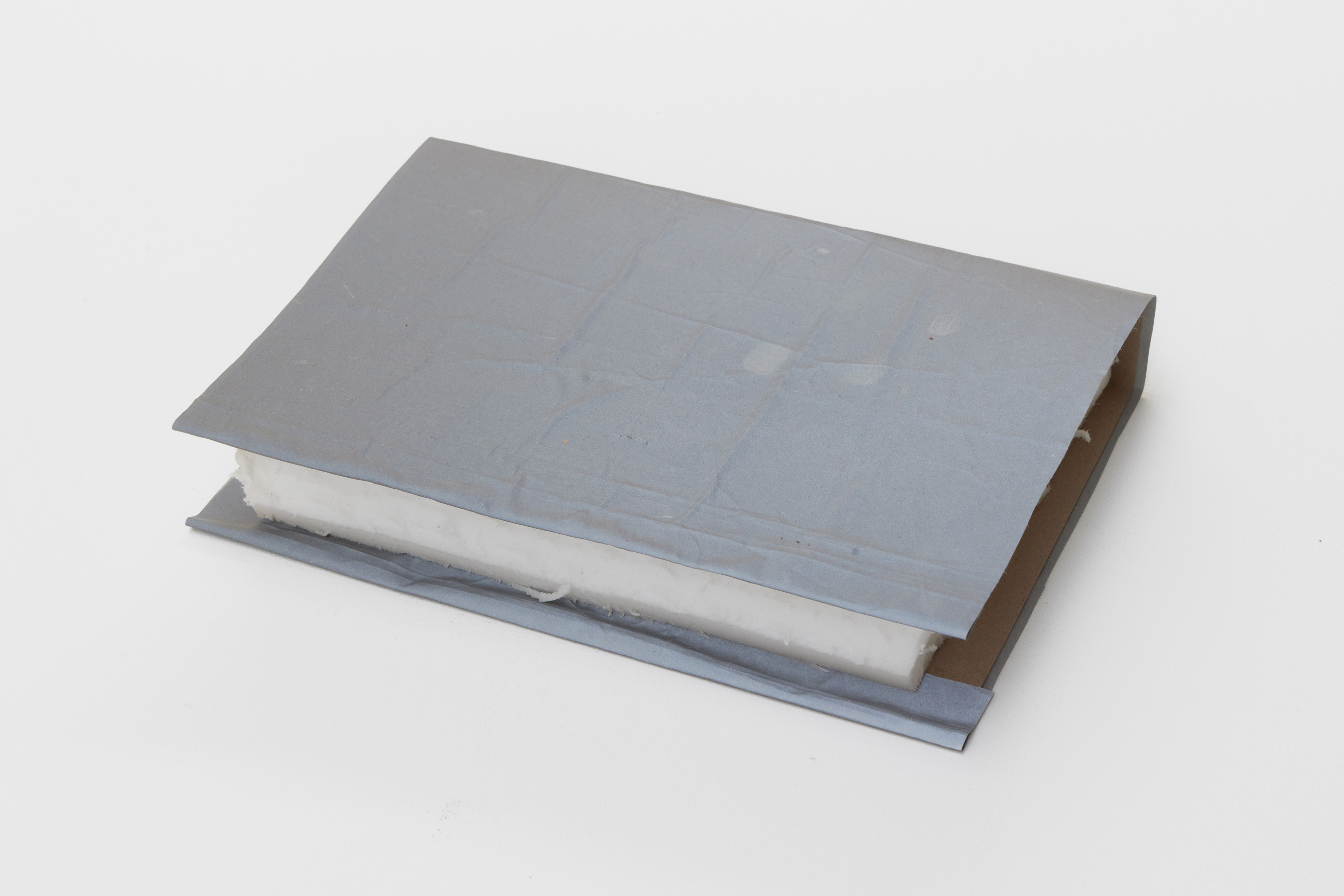

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Foam, fabric, 24 × 33 × 4 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Michael E. Smith, First, 2025, Coins, wires, cow bell, electric tape, speed bag, 49 × 29 × 20 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. Photo: Alex Kostromin

Defying Gravity

The first time I visited Capc in Bordeaux, where I currently work, was during the Christmas holidays in 2013. I was staying a few days with the parents of my roommate in Vincennes, Elsa. At that moment, I was just days away from starting an internship at the Centre for Art and Landscape on the Vassivière Island, assisting with dismantling an exhibition by Fernanda Gomes and installing one by Sheela Gowda ("Open Eye Policy"). A few weeks later, I would begin another internship at the galerie Crèvecœur, at 4 Rue Jouye-Rouve, which was showing, at the time, Renaud Jerez ("Adideath"). I had managed to negotiate skipping some of the bachelor degree classes to be able to work.

During that first visit to the Capc, one of the exhibitions on display was a solo by the American artist Michael E. Smith, invited by Alexis Vaillant. It was held in the side galleries on the ground floor. By then, I was not familiar with the artist’s practice and I wouldn’t immediately register his name. But impressions of his exhibitions lingered with me—particularly that of a baby car seat suspended on the wall, refracted by a decomposed, multicolored halo of light. By the end of 2014, I would encounter his work again—this time at Crédac in Ivry, in an exhibition curated by Chris Sharp ("THE REGISTRY OF PROMISE 3 – The Promise of Moving Things"). It felt like recognizing someone’s face without being able to recall where and when we had met.

One of the works he exhibited there was installed in the art center’s entrance, on the ceiling: both the first and last piece of the show. Composed of a tangle of cables and computer connectors, its tentacle-like appearance reminded me of Marvel’s Venom. Chris Sharp wrote about Michael E. Smith’s work that it «emanates an eerie impression of the human body, something akin to possession.»

The following year, in 2015, as I moved to London and started another internship with Vincent Honoré at the David Roberts Art Foundation, several works by Michael E. Smith were included in the group exhibition "Albert the kid is ghosting." In a space on the outskirts of the central galleries, a bicycle frame laid on the ground, at the end of which was attached a bottle of pesticide ("Spectracide: Wasp & Hornet Killer"): a prototype for an extinction machine. While Googling "Vincent Honoré Michael E. Smith," I came across an interview Vincent had given to Trébuchet magazine in 2014. To the final question, "Who do you think is the artist to watch at the moment and why?" he answered: "At the moment, I am particularly looking at the sculptures and videos of Michael E. Smith. They translate a sense of loss and ruin which echoes, often with humour, our current state of idealogical uncertainty."

This was followed by several "direct" encounters with the artist’s work (at KOW in Berlin, Modern Art in London, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and MoMA PS1 in New York), and a growing—though probably illusory—sense that I could decipher his language. I noticed recurring motifs, such as animals: stuffed, dried, skinned. Sometimes recognizable (a parrot, a pufferfish), other times transformed or abstract (columns of wings, furry cubes); the use of domestic furniture (sofas, chairs, tables); and manipulation of light—its removal (primarily) but also its addition (via lasers). Always present was a sense of life within the inert, and at times, a «pause» or «glitch,» a spasm.

For the 13th Baltic Triennial—on which I worked—I installed several works by Michael E. Smith at the CAC in Vilnius. The installation protocols, coupled with a FaceTime session with the artist and his assistant, helped me understand the importance he placed on balance, distance, gravity, and breathing (between the works themselves but not only). This installation experience coincided with the writing of the first text I wrote about his work—the only one to date. I then attempted to draw a parallel between the experience of flying over Detroit under snow and his exhibitions.

In recent years, several of Michael’s works have particularly struck me. One of them was a Pikachu plush toy stuck to a metal bar behind a window. A floating evicted Pokémon, left out in the street, seemingly ready to do anything to get back inside. This was at Paris Internationale in 2019, before the lockdowns. Another was two overturned kayaks that resembled, in the dim gallery of Modern Art in London, cetacean bones. I visited this exhibition with my then-boss, Sam Thorne. It was the first time I met Mike in person. As he hovered his hands over one of the two overturned kayaks, a heavy engine noise began, transforming into a high-pitched whale cry as his hand moved toward the opposite end of the vessel’s hull.

These past few days, I’ve spent several hours with Mike, often late into the night. Between conversations about the exhibition we were assembling and our lives, he shared music, images, and GIFs, as well as the name of an artist I didn’t know—Jim Drain—who now teaches his son. Memories of video games surfaced—particularly of a creature from the Mario universe called "Pokey." A cartoon I hadn’t known ("Beavis and Butt-Head") made me realize we weren’t of the same generation. The presence of basketballs also reminded me that I hadn’t touched one in ages (while images of works by David Hammons and Jeff Koons jostled in my mind). One evening, he also showed me an Instagram reel that had recently struck him. It featured a monkey on a leash playing fearlessly with a threatening cobra. The video was captioned, «-"When You Just Don’t Care About Problems Anymore 🤣. " The reel’s tagline read: “Unbothered.”

Cédric Fauq