Nicky Sparre-Ulrich

Vanishing Act

Project Info

- 💙 Tørreloft, AGA Works

- 🖤 Nicky Sparre-Ulrich

- 💜 Nanna Balslev Strøjer

- 💛 Brian Kure

Share on

Nicky Sparre-Ulrich, Vanishing act, exhibition view, Tørreloft, AGA Works, Copenhagen

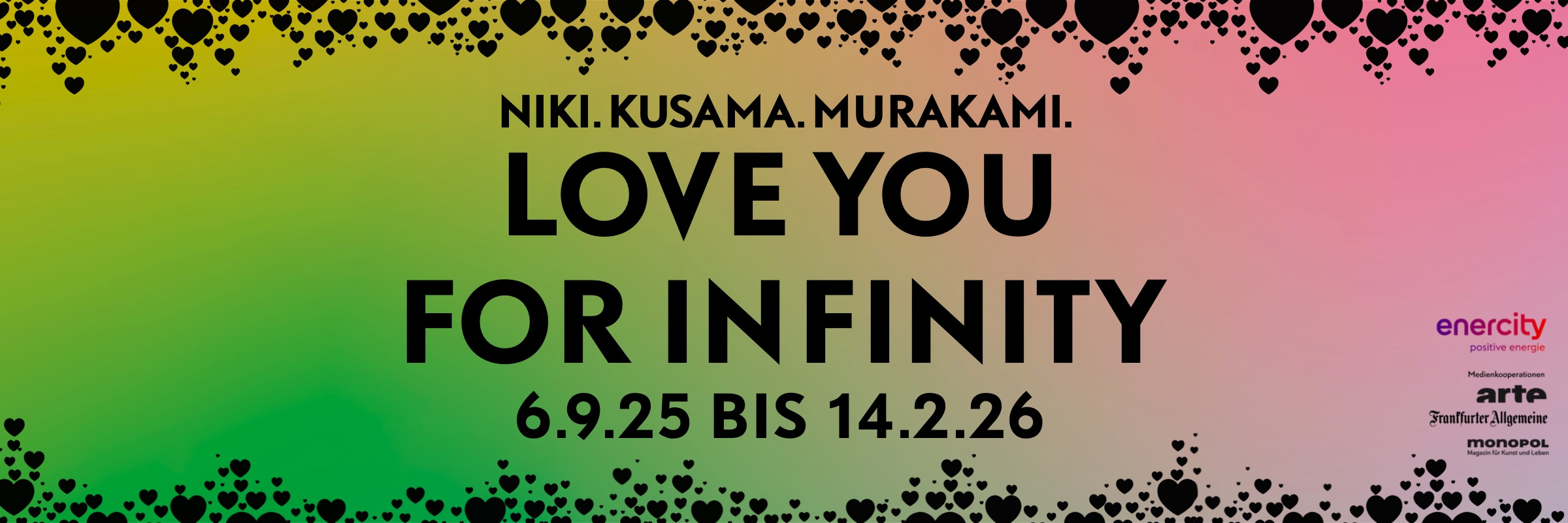

Advertisement

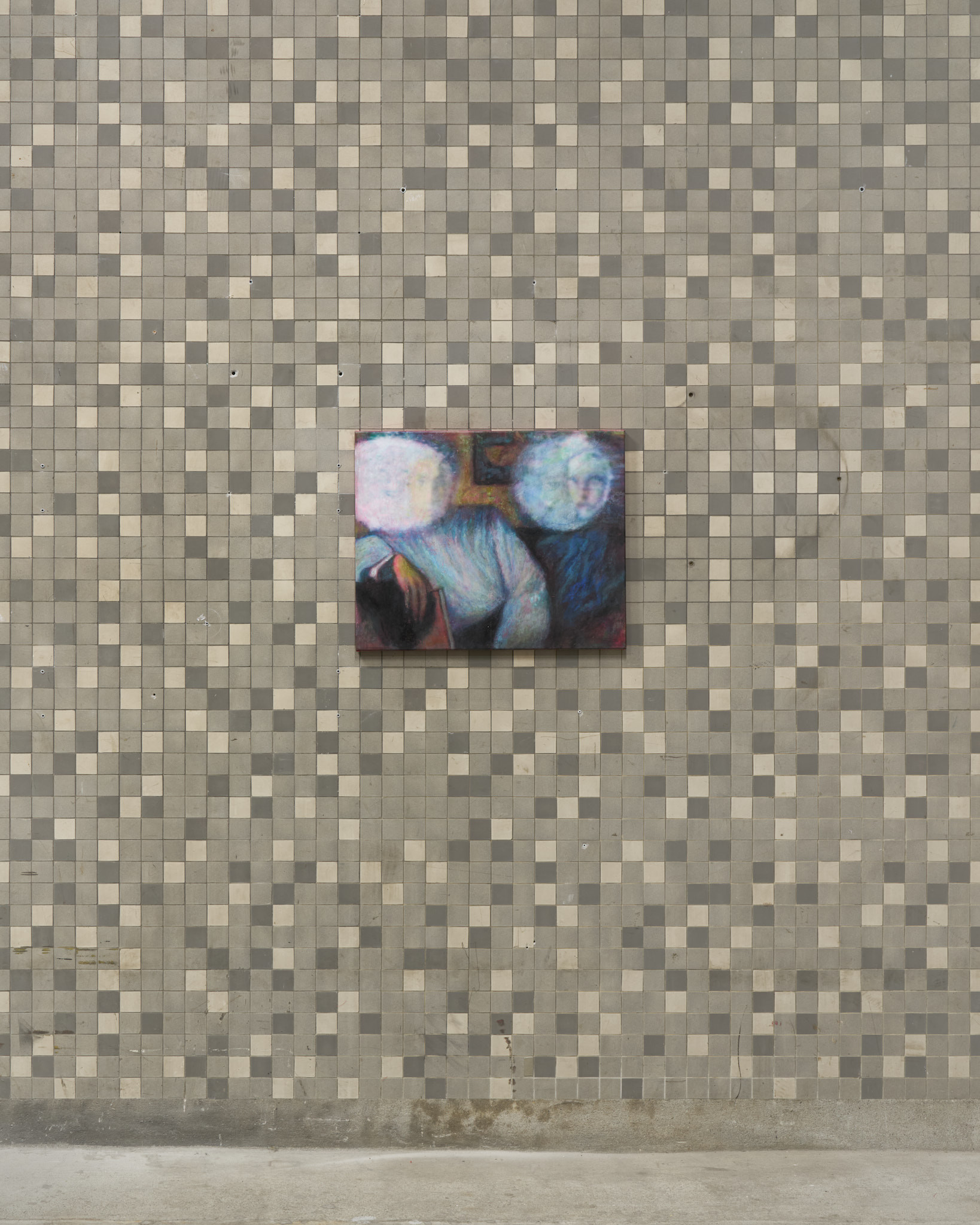

Boris and Alexander, Mixed media on canvas. 53 x 64 cm

Augusta, Mixed media on canvas. 114 x 94 cm

Augusta, Mixed media on canvas. 114 x 94 cm

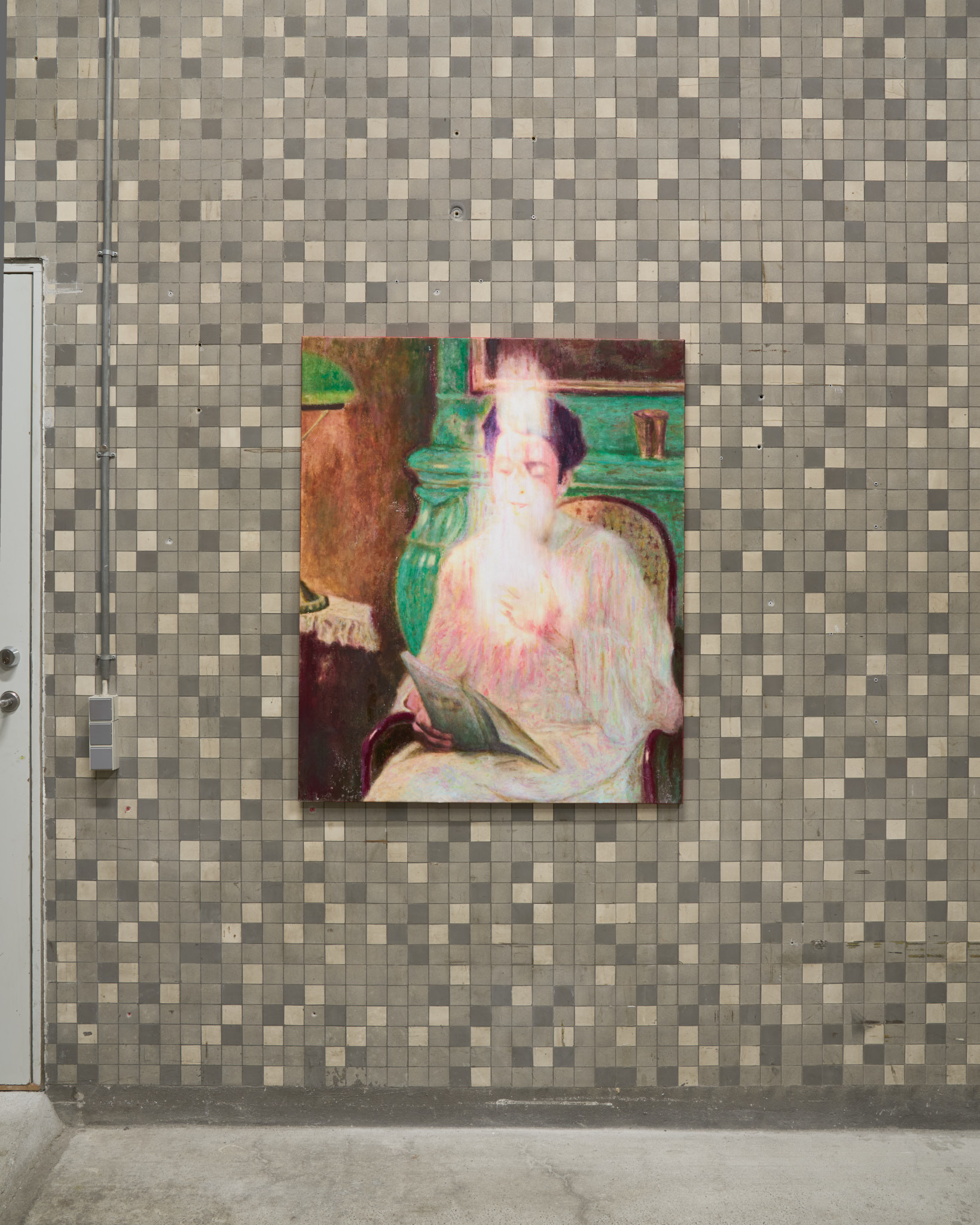

Reading by the green lamp, Mixed media on canvas. 51 x 74 cm

Nicky Sparre-Ulrich, Vanishing act, exhibition view, Tørreloft, AGA Works, Copenhagen

The Worker, Mixed media on canvas. 82 x 58 cm. Uncle Osip, Mixed media on canvas. 90 x 58 cm

Two Daughters, Mixed media on canvas. 130 x 90 cm

Untitled, Mixed media on canvas. 48 x 34 cm

Torments of Creative Work, Mixed media on canvas. 100 x 127 cm

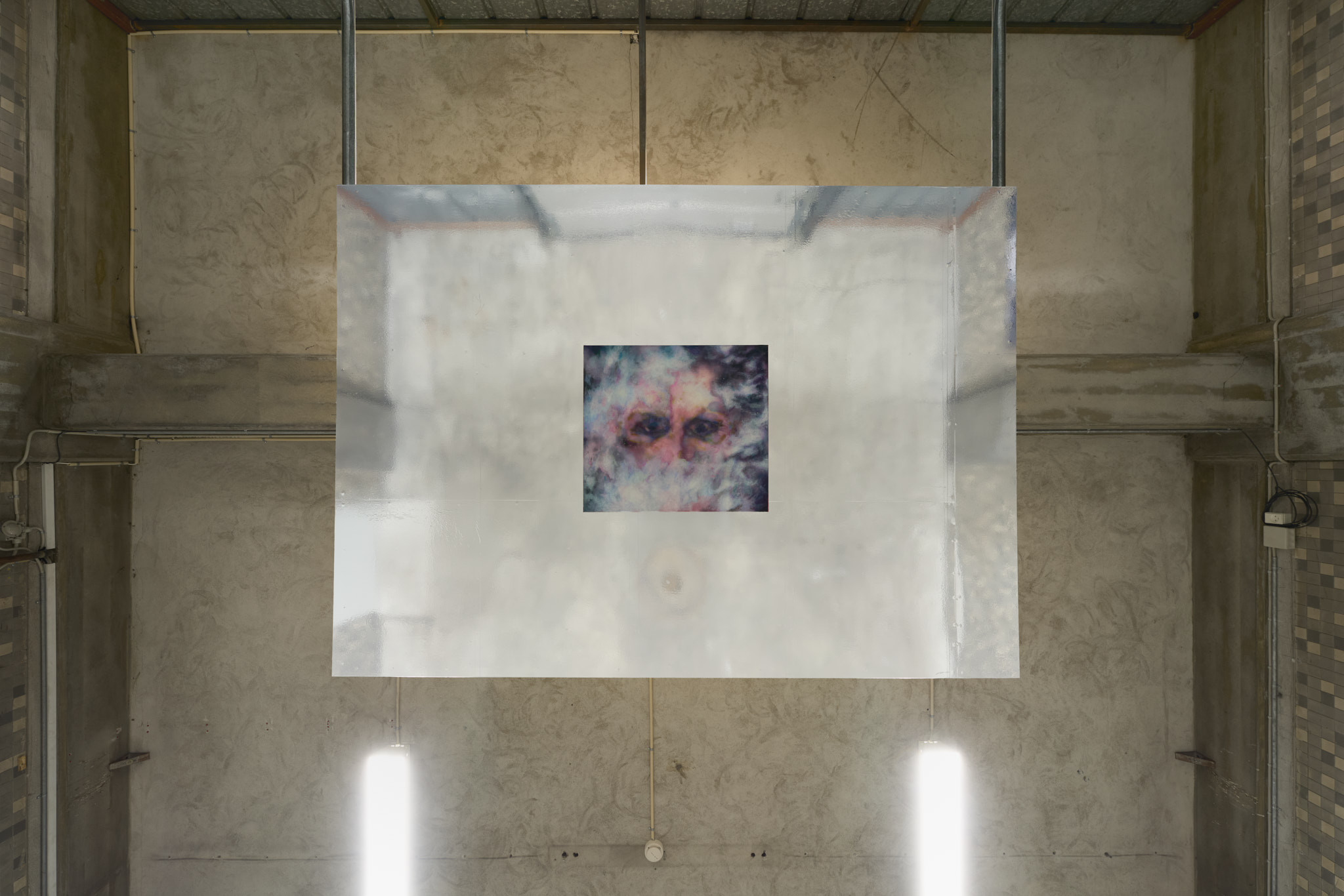

Cloud, Mixed media on canvas. 64 x 71 cm. (Mounted on wooden panel with mirror foil)

Cloud, Mixed media on canvas. 64 x 71 cm. (Mounted on wooden panel with mirror foil)

Nicky Sparre-Ulrich, Vanishing act, exhibition view, Tørreloft, AGA Works, Copenhagen

Vanishing Act

How is history constructed? Who decides what is preserved or forgotten? What is seen, and what is obscured? The exhibition Vanishing Act is a poetic and critical exploration of the fragility of memory and history. Drawing from Nicky Sparre-Ulrich’s own family narrative, the exhibition unfolds like the figures of a matryoshka doll—each layer of meaning splits apart to reveal the next, interweaving connections between an intimate family story and global political questions about the significance of truth in a ‘post-truth’ era.

When Russia invaded Ukraine nearly three years ago, it prompted Nicky Sparre-Ulrich to delve deeper into his own origins and family history—particularly a specific branch of the family that had lived in Odessa for generations, whose lives in many ways intertwine with the present. This connection is partly due to Sparre-Ulrich’s father’s extensive genealogical research, but more importantly, in this context, it is tied to a series of paintings by the Russian-Ukrainian impressionist Leonid Pasternak (1862–1945). Leonid Pasternak was the uncle of Sparre-Ulrich’s great-grandfather and, to the extent that one can use the word ‘always’ in an exhibition about history, his works have always hung in the Sparre-Ulrich family home. Pasternak and his artistic endeavors have thus held a certain presence in Nicky Sparre-Ulrich’s consciousness since childhood, and stories about him and his famous writer son, Boris Pasternak, have taken on an almost mythical quality within the family.

In the exhibition Vanishing Act, a selection of Pasternak’s portrait paintings serves as the foundation for a series of new works in which Sparre-Ulrich, like a magician, has erased or blurred the faces of the subjects. The paintings have been meticulously and delicately reworked, emerging as vibrant and dynamic works in their own right. The red edges create a three-dimensional effect, simultaneously emphasizing the composite nature of the works and subtly anchoring them in a contemporary context. The domestic, intimate scenes—a woman reading, a man at his desk, brothers side by side on the family sofa—become fragmented traces of the past, confronting the viewer as anonymous outlines of what once was. The dissolution of the portrait and the painting’s originality bring to mind a passage from the Russian writer Maria Stepanova’s novel In Memory of Memory: “The past has become pasts: parallel existing layers or versions that often have very few points of contact. Hard facts become wax-like and malleable. The desire to remember, recreate, and establish easily goes hand in hand with an incomplete knowledge and understanding of the past.” The works thus not only highlight the artist’s ability to create illusory worlds but also underscore how both memory and history are constantly subject to negotiation and manipulation.

The fact that history and what we perceive as ‘reality’ are malleable constructs means that image manipulation has been, and remains, a powerful and effective tool for political propaganda. In the early stages of his research for the exhibition, Sparre-Ulrich came across the book The Commissar Vanishes, which documents how Stalin used image manipulation to erase officials or other ‘undesirable’ individuals from history. The book shows examples of photorealistic paintings created from photographs, where one or more people have been removed, after which the painting is photographed and presented as a new original. This form of elimination from history feels inherently violent, and one cannot help but shudder at how concepts like ‘fake news,’ ‘deep fakes,’ and ‘disinformation’ shape our political reality today. The exhibition thus elevates itself from the personal narrative and the formal artistic exploration of the relationship between painting and photography to a highly relevant commentary on our contemporary world.

The paintings are classically hung in the exhibition space, with the exception of one work, Cloud, which is mounted on a mirrored foil ceiling. The motif, like the other works, is based on one of Leonid Pasternak’s portraits (though zoomed in), but here it is not the face that is erased—rather, the background dissolves around it. A pair of eyes staring through a cloud, gazing down on the viewer, evoking a sense of being watched. The viewer’s own gaze and observing body are reflected in the mirror, becoming part of the overall composition that unites the subject, the viewer, and the surrounding world into one. Sparre-Ulrich highlights the complexity of working with historical material and connects it to a contemporary era where the surveillance society is at its peak. The gaze from the cloud serves as a reminder that there is something greater than ourselves—whether it is something divine or the ‘digital cloud’ is for the viewer to decide.

Text: Nanna Balslev Strøjer

*In Memory of Memory, Maria Stepanova, New Directions Publishing Corporation, 2021

Nanna Balslev Strøjer