Hêlîn Alas

Dasein

Hêlîn Alas – Dasein, Installation view

Advertisement

Hêlîn Alas - Dasein 1, 2025, Sheet metal, decorative elements, acrylic glass, 120 x 60 x 60 cm

Dasein 1, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 1, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 1, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 1, 2025 (detail)

Hêlîn Alas Dasein 2, 2025 Sheet metal, lacquer, acrylic glass, 180 x 50 x 50 cm

Hêlîn Alas - Dasein 2, 2025, Sheet metal, lacquer, acrylic glass, 180 x 50 x 50 cm

Dasein 2, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 2, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 2, 2025 (detail)

Dasein 2, 2025 (detail)

Hêlîn Alas – Dasein, Installation view

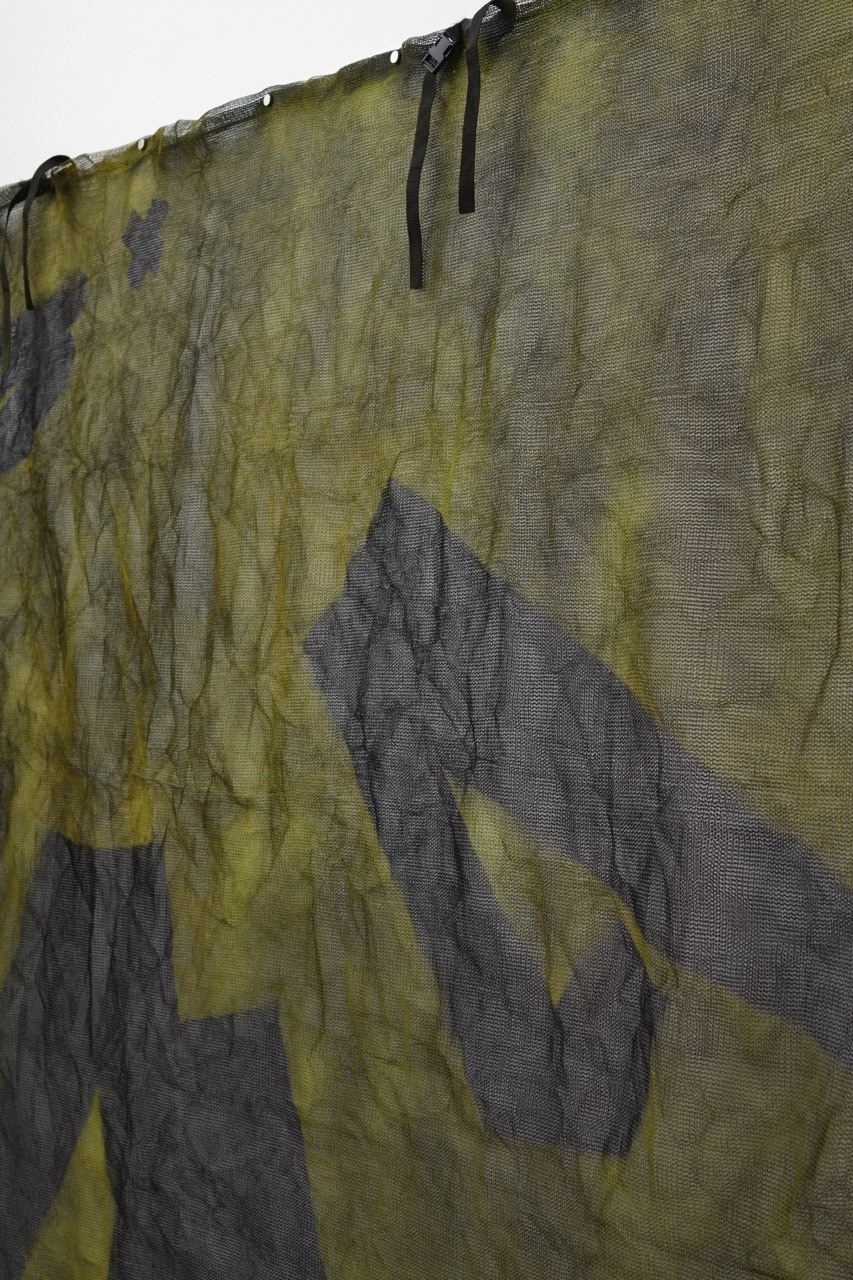

Hêlîn Alas - The word safe is never a verb, 2025, Safety net, lacquer, 180 x 565 cm

The word safe is never a verb, 2025 – (detail)

The word safe is never a verb, 2025 – (detail)

The word safe is never a verb, 2025 – (detail)

The word safe is never a verb, 2025 – (detail)

The word safe is never a verb, 2025 – (detail)

“There’s a melancholy associated with objects [but] it is we who are to be lamented, and not the objects that evoke this emotion in us without ever feeling it themselves.” (Peter Schwenger, The Tears of Things)

Hêlîn Alas’s sculptures and installations often begin with the observation that we not only determine the meaning of objects, but that objects, in turn, define us. The artist incorporates found, usually discarded, everyday objects into her work, testing their identity-creating potential. After all, the way we use objects reflects our desire to express a particular self-image as we navigate social norms. The sun figurines (a secondhand purchase) suspended in acrylic boxes point to past gestures meant to aesthetically shape a personal living environment. These figurines once greeted their owners with stoic friendliness, their presence promising a harmonious Dasein (Being) at home. Their use suggests that where there is no place for the horrible, where it cannot be allowed to exist, kitsch emerges as a way to de-demonize and ward off the darker aspects of life. The decorative miniature suns symbolize not only a longing for comfort, but also the dependence of our internal feelings and perceptions on an external object.

In Cruel Optimism, Lauren Berlant writes: “All attachment is optimistic, if we describe optimism as the force that moves you out of yourself and into the world in order to bring closer the satisfying something that you cannot generate on your own but sense in the wake […] of an object […].” Berlant argues that optimism becomes cruel when our desires or attachments actually hinder, rather than enhance, our ability to thrive— much like a situation of deep uncertainty that somehow feels affirming or reassuring. Like kitsch, unattainable fantasies of the “good life” serve to deny uncomfortable inner truths. They make reality more bearable by absorbing contradictions and suppressing negative emotions.

Attachment to self-deceptive thought processes is similarly explored in Alas’s large-scale wall installation. A safety net, typically used around a trampoline, is displayed flat against the wall, with the recognizable outlines of objects suggesting the human body arranged to create an illusion of depth. To convey a sense of three-dimensionality, Alas uses graphic principles typically taught to children in school. The notion of space here is based on rules for distinguishing between proper and improper perspective. According to this logic, as long as all lines lead to the vanishing point, you’re on the right track.

In Alas’s series of sun figurines, their rays occasionally caught in holes in glass walls, this idealized perspective appears to falter. The damaged surfaces show traces of physical pressure, transforming the once indifferent, grinning faces into expressions of suffering—shifting their symbolism from one of optimism to that of something burdensome.

The word trauma originally referred to a wound or puncture caused by a sharp object. And yet, it is only in the acknowledgment of a wound that its healing becomes possible. What has been repressed is brought to the surface by cracks and fractures in the suns faces: confronting pain is a prerequisite for regeneration and any form of constructive action.

In this way, Alas’s works suggest that understanding how to let go is an essential mode of existence, a key to Dasein.

Susanne Mierzwiak