Didem Erbaş

As the Land Falls Apart

Didem Erbaş, As the Land Falls Apart, Installation shot

Advertisement

Didem Erbaş, As the Land Falls Apart, Installation shot

Didem Erbaş, As the Land Falls Apart, Installation shot (Photo: Zeynep Fırat, courtesy of SANATORIUM)

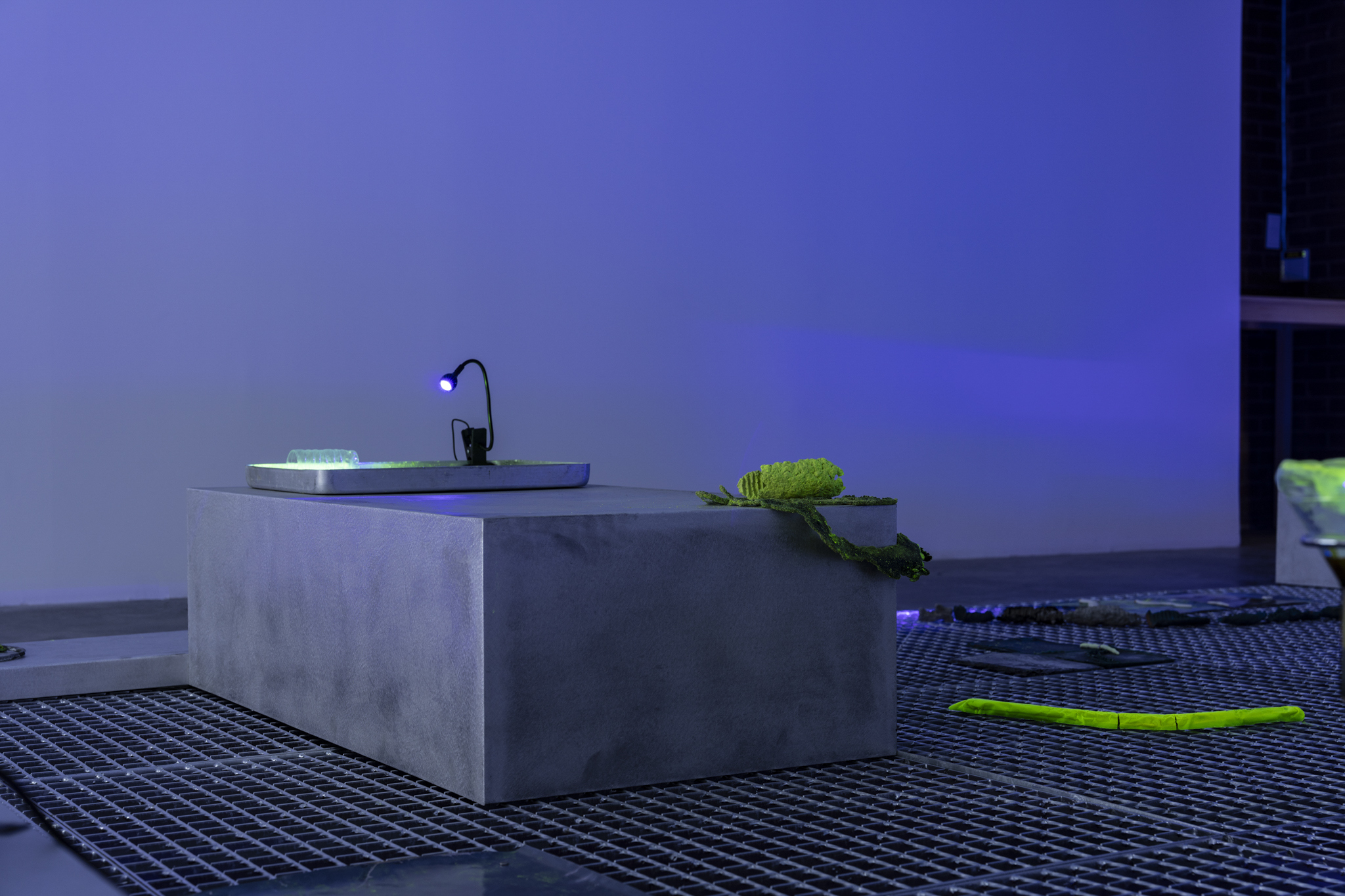

Didem Erbaş, Sparkles Under The Ground, 2025, Installation, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, Sparkles Under The Ground, 2025, Installation, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, Sparkles Under The Ground, 2025, Installation, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, Sparkles Under The Ground, 2025, Installation, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, Night Sight, 2025, Charcoal on paper, UV flashlight, 375 x 150 cm

Didem Erbaş, Night Sight II, 2025, Charcoal on paper, UV flashlight, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, Night Sight II, 2025, Charcoal on paper, UV flashlight, Dimensions variable

Didem Erbaş, As the Land Falls Apart, Installation shot

Didem Erbaş, Temporary Hosts, 2025, Video, sound, 5+1 AP, 04’09’’, (Text and Reading by Helen Brecht, Translation from German to Turkish: Dilek Erbaş, Video Edit: Melih Kaymaz)

Didem Erbaş, Temporary Hosts, 2025, Video, sound, 5+1 AP, 04’09’’, (Text and Reading by Helen Brecht, Translation from German to Turkish: Dilek Erbaş, Video Edit: Melih Kaymaz)

Didem Erbaş, Sparkles Under The Ground, 2025, Installation, Dimensions variable

Elle rigavan lor di sangue il volto,

che, mischiato di lagrime, a’ lor piedi

da fastidiosi vermi era ricolto.

— Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, Inferno, Canto III

By wasps and hornets, which bedew’d their cheeks

With blood, that mix’d with tears dropp’d to their feet,

And by disgustful worms was gather’d there.

— Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Hell, Canto III

Tomris Uyar says, “The more you look, the more you get used to its ugliness, its frightening nature fades away,” while Eric Fromm reminds us, “Si vis Pacem para bellum” (If you want peace, prepare for war). The exhibition holds the viewer on an ambiguous boundary between life and death, offering mappings that emerge from these limits.

At the center of the exhibition is Das Kriegsspiel, a modern adaptation of the Kriegsspiel developed in the 19th century by Georg von Reisswitz to teach battlefield tactics to the Prussian army. Johan Huizinga argues that play (ludus) is a fundamental element of culture. In this context, war games are not merely simulations of the past but also emerge as cultural and cognitive experiences. According to Paul Virilio, what was once a structured military war game, Kriegsspiel, has evolved into different forms of modern warfare. Although the traditional Kriegsspiel no longer exists in its original form, its principles continue to persist in new domains such as terrorism and information warfare. Information warfare, in which technology and information manipulation have become critical strategic tools, represents a new battlefield. This shift signifies a revolution in military doctrine, transforming warfare from physical conflict to digital and psychological operations. Therefore, Kriegsspiel has not disappeared but has adapted, now existing as a game played with information and technology in the corridors of power.

In the exhibition space, the boundaries between destruction, transformation, and survival dissolve, creating a realm shaped by both human and non-human forces. The traces left by war machines intertwine with those left by worms, turning the gallery into a repository of remnants and imprints. The boundaries between objects, living beings, and targets become fluid. Entities and materials aim to transcend the limitations of ordinary metals, transforming in the process, seeking immortality through the philosopher's stone. This transformation evokes alchemical principles like solve et coagula, symbolizing a process where destruction and rebirth intertwine. After all, as Isaiah 66:24 reminds us, “The worm that devours them will not die, and the fire that burns them will not be quenched.”

Familiar earthworms and leeches belong to a larger group called annelids. Annelid worms are among the most abundant and diverse animal groups alive today. They evolved in the oceans 500 million years ago, gradually colonizing a range of ecosystems from terrestrial soils to the seas. Despite their soft bodies being prone to rapid decay after death, they have left behind a rich fossil record in rare and unique geological sites, with their skin, intestines, and muscle tissues preserved. Tullis Onstott’s discovery of microscopic roundworms (nematodes) living about four kilometers beneath the Earth's surface in gold mines in South Africa made headlines as "worms from hell." The human relationship with worms, driven by the quest for immortality, is rooted in some of humanity’s oldest fears. Herodotus recounts the fear Egyptians had that worms would consume their dead, while Dante’s Inferno speaks of terrifying giant worms. Edgar Allan Poe famously wrote, "And the hero, the Conqueror Worm," while today, Ashnikko echoes the sentiment, singing, "The world is burning, worms in my brain."

While worms, maggots, and larvae may seem distant possibilities in our everyday city life, the artist brings them to the forefront, either by unearthing them or inviting us underground into their world. This encounter challenges us to confront the boundaries between life and death, offering a space where both utopian and perhaps dystopian connections unfold.

In La Poétique de l’Espace, Gaston Bachelard speaks of the dialectical nature of a living being emerging from a shell, noting the contradiction between the part of the creature that has emerged and the part that remains inside. He describes how its back is trapped in rigid geometric forms. Using the shell as a metaphor, Bachelard bridges the gap between freedom and bondage, stating, “We want to see, but we are also afraid to see.” He further suggests that a creature’s hiding is essentially a search for an exit, whether it be from a grave to resurrection or from silence to an eruption of anger.

In Le Bestiaire du Christ, Louis Charbonneau-Lassay defines the human existence as a symbol of the unity between body and spirit in ancient times, where, upon the departure of the spirit, the body’s lifelessness remains in the shell once the animating force has left. Meanwhile, in his manifesto Vers Une Architecture, Le Corbusier asserts, “A house is a machine for living in.”

In the exhibition space, the snails that follow us, along with the shells we encounter, challenge us to witness the struggle for survival through the lenses of machine, body, human, and non-human creatures. It forces a confrontation between passive witness and active participation, merging objects and goals through different forms, compelling us to experience the effort of existence between life and toxic remnants within this fragile ecosystem.

"Copying the relation of man to man brings us back to parasitism. (…) The parasitic relation is intersubjective. It is the atomic form of our relations. Let us try to face it head-on, like death, like the sun. We are all attacked, together." (Serres, Parasite, 8) Migration and displacement—are these actions solely ours? What do we take with us? For instance, in the 15th century, Northern Europeans brought with them parasitic fish infestations when they traveled to Jerusalem, something we only learn today through archaeological research. So, what will we leave behind?

In As the Land Fall Apart, visitors are invited to reconsider how we mark time. The exhibition challenges the rigid distinctions between humans and non-humans, presenting a landscape where these forces intertwine, leaving traces of transformation and decay. It maps destruction as an evolving archive of human consumption; here, debris becomes both a target and a permanent imprint of transience. The applied grid system serves as an attempt to organize disorder, questioning how control systems emerge in spaces of waste and ecological collapse.

In this exhibition, Didem Erbaş shares the traces and maps of her journey through various methods and materials. During her time at the Delfina Foundation Residency program in London, she drew from documents and archival research gathered from places such as the Hunterian Museum, the photographic collection of the Warburg Institute, and her time spent in New York. Erbaş creates installations from found objects she collected while walking, intertwining them with SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope) images she has manipulated. A video merges these images with a text read aloud by Helen Brecht in her own voice. Through this multifaceted approach, Erbaş invites us to explore not only her personal journey but also the transformative processes of research and discovery.

Irmak Keskin