Rebekka Benzenberg

Dream Baby Dream

Project Info

- 💙 Galerie Anton Janizewski

- 🖤 Rebekka Benzenberg

- 💜 Malte Lin-Kröger @malte.lin.k

- 💛 Julian Blum @exhibitiondocumentation

Share on

Installation view

Advertisement

Rebekka Benzenberg They Longed For An Ancient Tragedy, 2025 Worbla, UV resin, epoxy resin, glass fibre fabric, fabric 60 x 160 x 60 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Rebekka Benzenberg Or don’t you know what to look for?, 2025 Speakers, lampshades, cables, amplifiers 150 x 150 x 80 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Rebekka Benzenberg Peace will come and with it sleep 2025 Worbla, UV resin, epoxy resin, glass fibre fabric, woven fabric, satin fabric, king-size duvet, sheet, feather down pillow, spring mattress, aluminium frame 200 x 100 x 160 cm

Rebekka Benzenberg Tell me what you know about dreams, dreams 2025 LEDs, aluminium housing, cable, dimmer 280 x 180 x 100 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Rebekka Benzenberg Doing Comes From Being Itself, 2025 Plexiglas, wooden plate, make-up palette, socks, towel, eiderdown pillow, pants, bedspread 90 x 185 x 15 cm

Rebekka Benzenberg For Stories To Live, 2025 Plexiglas, wooden board, duvet, down pillows, pillowcases, duvet covers, bedspread, make- up remover wipes, pyjama bottoms, T-shirt, heat plasters 90 x 185 x 15 cm

Installation view

Rebekka Benzenberg I cover you in a blanket, 2025 Worbla, UV resin, epoxy resin, glass fibre fabric, fabric, stand 100 x 170 x 80 cm

Installation view

Rebekka Benzenberg Dream Baby Dream, 2025 Wooden board, plexiglass, spacer, down cush- ion, fitted sheet, staple pins 80 x 80 x 10 cm

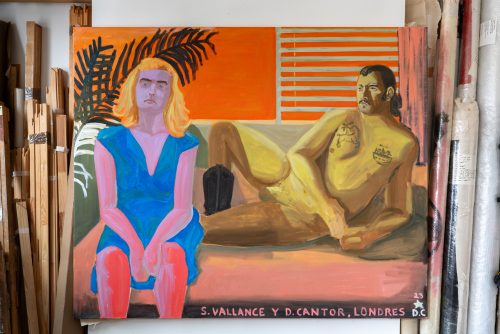

Rebekka Benzenberg, All be fine, 2025 Oil on canvas 155 x 120 cm

Exhaustion as an expression of resistance, depression as

a silent but fundamental indictment of a sick system: in her

exhibition Dream Baby Dream, Rebekka Benzenberg draws at-

tention to questions that are only superficially personal and

intimate. The motif of the bed is at the center of her pointed,

finely tuned compilation of sculptures, sound and paintings:

a tempting retreat and a hated sickbed at the same time. The

bed – especially the unmade one – implies a body that tosses

and turns in it, sweats and leaves traces of its presence be-

hind. Artists such as Tracey Emin and Louise Bourgeois have

established the bed as a cipher for the presence of female

bodies and their sexual self-determination in contemporary

art. Benzenberg draws on these role models and their impulse

to make the private public and thus political. The artist fo-

cuses on the body made invisible due to depression and iso-

lation and critically questions its pathologization: a perspec-

tive that looks at social contexts as a whole and understands

mental illness as described by the British revolutionary col-

lective Red Therapy in the 1970s: „A major form of reaction, of

our bodies’ rebellion, against capitalism”.

The market for psychotherapies is flooded with of-

fers that specialize in the elimination of symptoms but do

not identify and address systemic causes as such. Benzen-

berg’s work “Tell me what you know about dreams, dreams”,

which attracts attention with its hypnotic light that wanders

back and forth, is inspired by the approach of Eye Move-

ment Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR for short),

which is intended to support the therapy of traumatic expe-

riences through guided eye movements and is used, among

other things, for soldiers returning from war zones. Benzen-

berg makes it clear how technology specifically intervenes in

cognitive processes and is intended to maintain productivity

and perceived normal stress tolerance. On the other hand, an

unprecedented medialization and gamification of social life

undermine precisely such efforts. The sound work “Or don’t

you know what to look for?“ fills the exhibition space in an

endless loop with sounds from the puzzle game Candy Crush:

an app that, like many others, targets the brain’s reward sys-

tem by releasing a little dopamine with every candy puzzle

solved. This creates the illusion of an accomplished or fulfill-

ing task, but due to the endless nature of the game, the risk of

addiction should not be underestimated.

The sculpture lying in Benzenberg’s specially made bed

seems to be in this precarious limbo of therapy and para-

lyzing distraction. It is a cast of the Düsselnixe from Düssel-

dorf’s Malkastenpark that the artist has reworked and alien-

ated. The gleaming white doppelganger of Gustav Rutz’s work

from 1897 is accompanied by another replica that appears

twice in the room: an echo of Richard Langer’s bronze sculp-

ture Flora, once freestanding, once mounted on a tripod like

a spotlight. The original cast from 1920 – an interpretation

of the Roman goddess of spring, naked and youthful in the

look of German life reform – can be found behind glass in the

Mülheim Stadthalle. The sculpture did not survive the unpro-

tected public space, more precisely the Mülheim city garden.

It was smeared, sprayed and one of its arms was chopped

off. The artist’s doubling of the sculpture echoes the last,

unsuccessful attempt by the Mülheim city council to at least

preserve a copy of the Flora made from plastic at its original

location. Does this space offer her a newly created shelter?

Or is it just condemning it to a shadowy existence? The veils

that Benzenberg places over her sculptures make them recog-

nizable as shadowy memories rather than living bodies.

Depression can be perceived as disembodying; it also

means isolation. In this respect, it goes well with neoliber-

alism, whose maxim holds individual interests above all else

and demands adaptation from everyone. “Economics are

the method; the object is to change the heart and soul”, was

Margaret Thatcher’s principle. Writer and journalist Sophie K.

Rosa recognizes the widespread attitude, particularly among

millennials, that human life, like capital, must first accumu-

late value in order to be worth living. Otherwise, existen-

tial fear and depression loom – more than in any previous

generation. „A sense of security among loving community is

hard to come by, and solidarity with our neighbours perhaps

even harder. […] [S]peaking to each other, outside of private

homes, transactions, workplaces or planned socializing, is

uncommon, even considered suspect.” So what happens when

the heart and soul rebel?

Rebekka Benzenberg’s exhibition is a monument to a

condition that silently cries out to be overcome. This becomes

particularly clear in her paintings and wall works, which show

orphaned bedscapes and crumpled pillows and blankets. It

is not immediately clear from them whether the person lying

here has left the bed permanently or only for a moment before

returning to it. In any case, the bed does not appear invit-

ing here, but rather oppressive. In “Peace will come and with

it sleep“ it not only occupies the entire canvas, but virtually

merges with it – as if to say that under present conditions

there is nothing more to be imagined and depicted than this

oppressive imprisonment.

- Malte Lin- Kröger

(1) Sophie K. Rosa, Radical Intimacy, 2023, Pluto Press, S. 17

(2) Sophie K. Rosa, Radical Intimacy, 2023, Pluto Press, S. 19

Malte Lin-Kröger @malte.lin.k