Ville Laurinkoski

Ville Laurinkoski: Eve at Lou, Helsinki

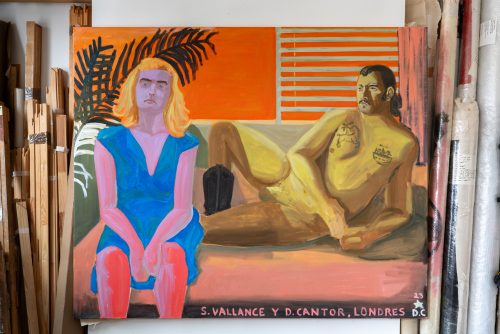

Performance

Advertisement

Performance

Performance

Installation view

Installation view

Detail

Installation view

In this exhibition, artist Ville Laurinkoski continues his ongoing engagement with the writing of French essayist, theorist, and gay activist Guy Hocquenghem. The novel Ève – from which the exhibition takes its name – was published in 1987, shortly before Hocquenghem's death from an AIDS-related illness. Reflecting the uncertainty and fear of the early AIDS crisis, marked by institutional failure and silence, Hocquenghem turns unexpectedly toward myth and religious symbolism, evoking Adam and Eve to grapple with mortality and transformation.

Over the years, Laurinkoski has systematically brought Hocquenghem’s writing into his own work through acts of translation: from French to English, from the written word into speech and sound, from a linguistic space into objects and material reality. For Laurinkoski, Hocquenghem’s writing and the context from which he wrote becomes a source of information to be processed and repurposed. Translation also becomes an act of negotiation; by bringing past texts into the present, Laurinkoski shows how access to information remains a contested terrain.

There’s hardly ever a balance of information. During the AIDS crisis poor, Black, and queer people were disproportionately affected by the lack of it, whereas now we face an excess of information we are fluent in consuming: endless notifications, advertisements, fake news, and deceptive images. It raises a question no less significant than: What is reality, and on whose terms?

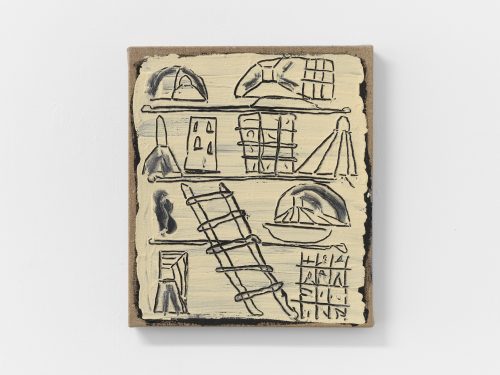

The installation includes a floor piece, a paper towel dispenser, a door, a book, a sound work, and a performance. These elements resist forming a systematic meaning. Laurinkoski relies not on visual tricks or deceptions, but on something more potent: a sense of lack. We’re missing backstories, clues, and identities; there are no bodies in sight.

The book in the space, printed in maraschino red, contains the entire novel Ève — translated with the help of online tools — alongside the performance score derived from the original text. In the score, dialogue from Hocquenghem’s novel is rearranged into fragmented, detached exchanges. These scenes lack moral resolution; their intensity lies in their incompleteness and out-of-place characters. This detachment reflects a reluctance toward connection — unsurprising, perhaps, when illness and loss render intimacy an unwanted affect.

The door placed by the artist in the doorway to the back room entices, yet also acts as a barrier, both mental and physical. Both reactions pose the question of what lies on the other side, though the feelings provoked differ. Is not knowing a blessing or a curse?

The works of the exhibition play with atmosphere and affect, rather than relying on the act of seeing as a form of interpretation. Still, the way Laurinkoski uses material culture, mass-produced objects, commercial products, text and sound, makes them part of a visual lexicon often overlooked. The affective space arises from the spatial and material. It can be felt, like a lukewarm cup of badly dissolved Nescafé.

Here, the everyday is infused with unease and enchantment, drawing out aspects of life that are usually left unspoken or unseen. We encounter familiar objects displaced just enough to unsettle. These details open onto a strange familiarity; a sense that you’ve seen this before, though you can’t quite grasp what it is you’re seeing. The space Laurinkoski creates certainly evokes memories and feelings, but perhaps not one’s own. The viewer is placed before something they don’t have to confront, but can no longer ignore: an unsolvable reality.

The novel Ève also draws on the myth of Narcissus, reframed by Hocquenghem through the mirror image, the other half and the double. In a scene, the protagonist, Adam, sees his reflection in the window of a crowded metro. To his pleasant surprise, the face gazing back at him is young and attractive, full of promise. Reflection becomes entanglement, a kind of last thread of hope when a sense of safety begins to dissolve.

You might catch an image of yourself in the reflection of the gallery window. Who do you think looks back at you?

Is not knowing a blessing or a curse?

Remi Vesala