Shinoh Nam

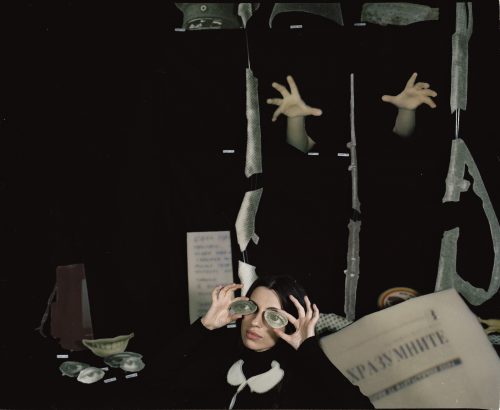

The Collapse

Shinoh Nam, The Collapse, installation view, ©StudioShinohNam

Advertisement

Shinoh Nam, The Collapse, installation view, ©StudioShinohNam

Shinoh Nam, The Collapse, installation view, ©StudioShinohNam

Floor : For those who became the floor for those who didn’t want to walk on the bare ground, 2025, wood, stainless steel, steel, hanji, 200(h) x 230 x 32 cm

Detail view

Portico: The columns surrounding him did not come to greet him, yet they stood firm for his sake #1: Mother, 2025, wood, stainless steel, steel, 280(h) x 230 x 200 cm

Detail view

Portico: The boy does not want to let go of the crown. Even now #3, 2025, wood, stainless steel, steel, 300(h) x 230 x 200 cm

Detail view

Portico: The columns surrounding him did not come to greet him, yet they stood firm for his sake #1: Old man, 2025, wood, stainless steel, steel, 300(h) x 230 x 200 cm

Detail view

Doorknob: with every Doors, against my hopes and certainties, 2025, Steel, stainless steel, 6(h) x 9 x 8 cm

Detail view

You cannot restrain me at all, and I shall perpetually bestow upon you a state of tenderness: HSBC Tower, 2025, Print on Art Canvas, stainless steel, pencil, Post-it, 150h x 105 cm

Detail view

You cannot restrain me at all, and I shall perpetually bestow upon you a state of tenderness: Flakturm Nazi Tower, 2024, Print on Art Canvas, stainless steel, pencil, Post-it, 150h x 105 cm

Detail view

The process of becoming the most humane architecture #3, 2025 Stainless steel, plexiglass, Aluminium, 205(h) x 18 x 16 cm

The process of becoming the most humane architecture #2: De Rotterdam, 2025, Stainless steel, plexiglass, Aluminium, 205(h) x 36 x 26 cm

Detail voew

In contemporary society, individual identities are often constructed, constrained, and even dissolved within established systems and structures. In the first solo exhibition of emerging South Korean artist Shinoh Nam, he critically examines how societal systems shape personal and collective identities through multiple media, including sculpture, installation, and sound. The works analyze and question social norms through structural formal language, presenting issues of individual visibility and marginality within institutional contexts.

The exhibition uses the “portico” as a symbolic starting point, an entrance in architecture that signifies order and belonging. However, in Nam’s work, this structure appears fragmented and broken. The entire exhibition is enveloped in a colorless atmosphere, creating a void and oppressive spatial ambiance. Charred, monumental beams stand on the floor, broken doorknobs are embedded in randomly arranged walls, simulating a spatial interface lacking clear orientation and function. In some installations, handwritten notes and miniature objects like pencils are suspended, injecting fragments of information into the overall structure, providing certain references without forming a complete narrative.

At the center of the exhibition, the surface of the pillar sculpture faintly reveals human contours—faces, shoulders, curves—seemingly pressed into the pillar and sealed within. These monumental sculptures evoke the tradition of using female bodies as columns in ancient Greek temples, where decorative elements conceal historical structures of gender and power1. From the moment their bodies became part of the temple structure, they were permanently embedded in a symbolic logic of service and subordination. This metaphor is further activated in Nam’s sculptures: each person, perhaps like those bodies, is both a supporter of the social structure and subjected to its structural oppression. Here, the boundaries between individual and society are blurred, with personal identity being shaped while simultaneously participating in shaping the structure itself. This dual relationship breaks the clear boundaries between individual and society, placing identity in a continuous flow and exchange between social roles and personal existence.2

Architecture is one of the most symbolic and material manifestations of human activity; it is not only a combination of dwelling and technology but also solidified social relations, as Henri Lefebvre noted3. It concentrates the crystallization of power, capital, technology, and labor. In Nam’s work, images of buildings that once symbolized prosperity, authority, and quality of life (such as the Nazi Flakturm tower and Hong Kong’s HSBC building) are distorted and interwoven with metal components symbolizing the “spine” of architecture. Among them, a small pencil and a note are quietly hidden in the gaps between components, representing the whispers of builders who once participated in construction— the only warmth within the cold structure. In these details, the tension between metal and pencil, photography and hand-drawing, mechanical and manual, compression and extension reveals the artist’s delicate attention to individuals, minorities, and the fate of laborers.

In Heidegger’s philosophy, he distinguishes between “ready-to-hand” (Zuhandenheit) and its state of failure4. Construction workers are truly “present beings” during the building process. However, once the building is completed, workers withdraw; their existence is regarded as the completion of the “tool,” their “use-value” disappears, and they are subsequently forgotten by society5. This phenomenon reveals a profound “instrumental life” situation in modern society: the value of individuals is confined to a certain production link, and once they are no longer useful, they are no longer seen or acknowledged.

Nam’s exhibition is a non-real, fictional yet precise stage. It resembles the absurd field constructed by de Chirico on a two-dimensional canvas, where components lack dialogue but constrain each other; all objects imply the absence of meaning and spiritual rupture. He creates “imbalance” in visuals and “discomfort” in everyday objects to evoke viewers’ reflection. As Camus wrote in “The Myth of Sisyphus”: “The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.”6 Nam’s work is the scene of this confrontation. His work does not emphasize emotional expression but presents how individuals are functionalized, symbolized, and marginalized within social mech nisms through the structural organization of space and the logical relationships between materials. At the intersection of architecture, power, labor, and symbolism, he attempts to guide viewers to reconsider the relationship between individuals and structures—after the structure is built, does the individual still exist? And is this existence seen?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Beard, Mary. Women & Power: A Manifesto. Liveright, 2017.

2 Hall, Stuart. Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In: Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, 1990.

3 Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Wiley-Blackwell, 1991.

4 Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Trans. John Macquarrie & Edward Robinson. Harper & Row, 1962.

5 Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, 1958.

6 Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Penguin, 2000.

NADAN