Ziva Drvaric, Helena Parada Kim

Distant Voices / Still Lives

Project Info

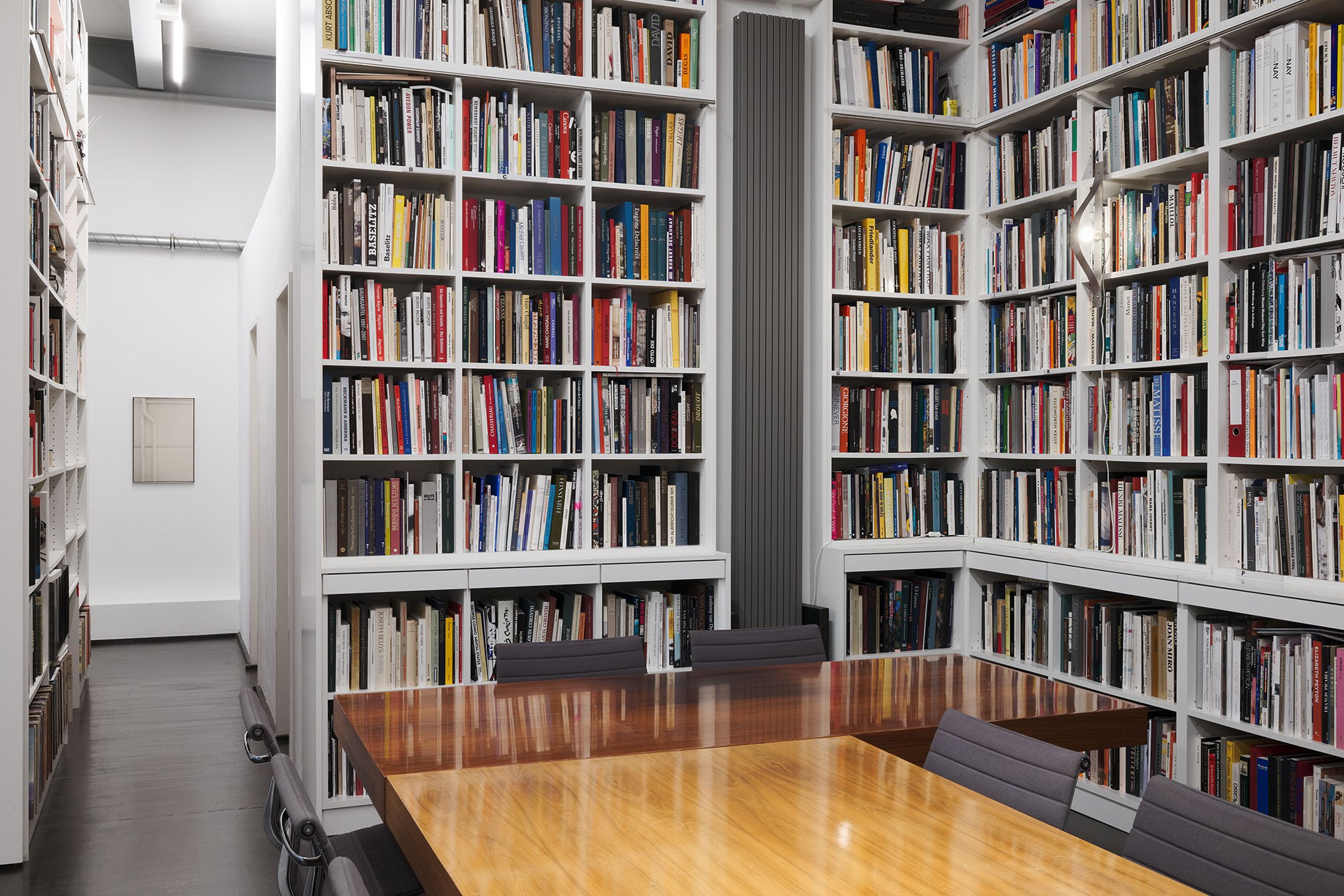

- 💙 Braunsfelder

- 💚 Vanessa Joan Müller

- 🖤 Ziva Drvaric, Helena Parada Kim

- 💜 Vanessa Joan Müller

- 💛 Mareike Tocha, Cologne

Share on

Advertisement

Distant Voices / Still Lives

The title of the exhibition is adapted from Terence Davies’ film Distant Voices, Still Lives, an impressionistic montage about his childhood in Liverpool in the 1940s and '50s. Here, two artistic perspectives engage in dialogue, translating moments of remembrance and the negotiation of identity into suggestive and conceptual visual languages.

The works of Helena Parada Kim and Ziva Drvaric explore approaches to the past, including the biographical, as well as the points at which the self, the other, experience and memory become blurred.

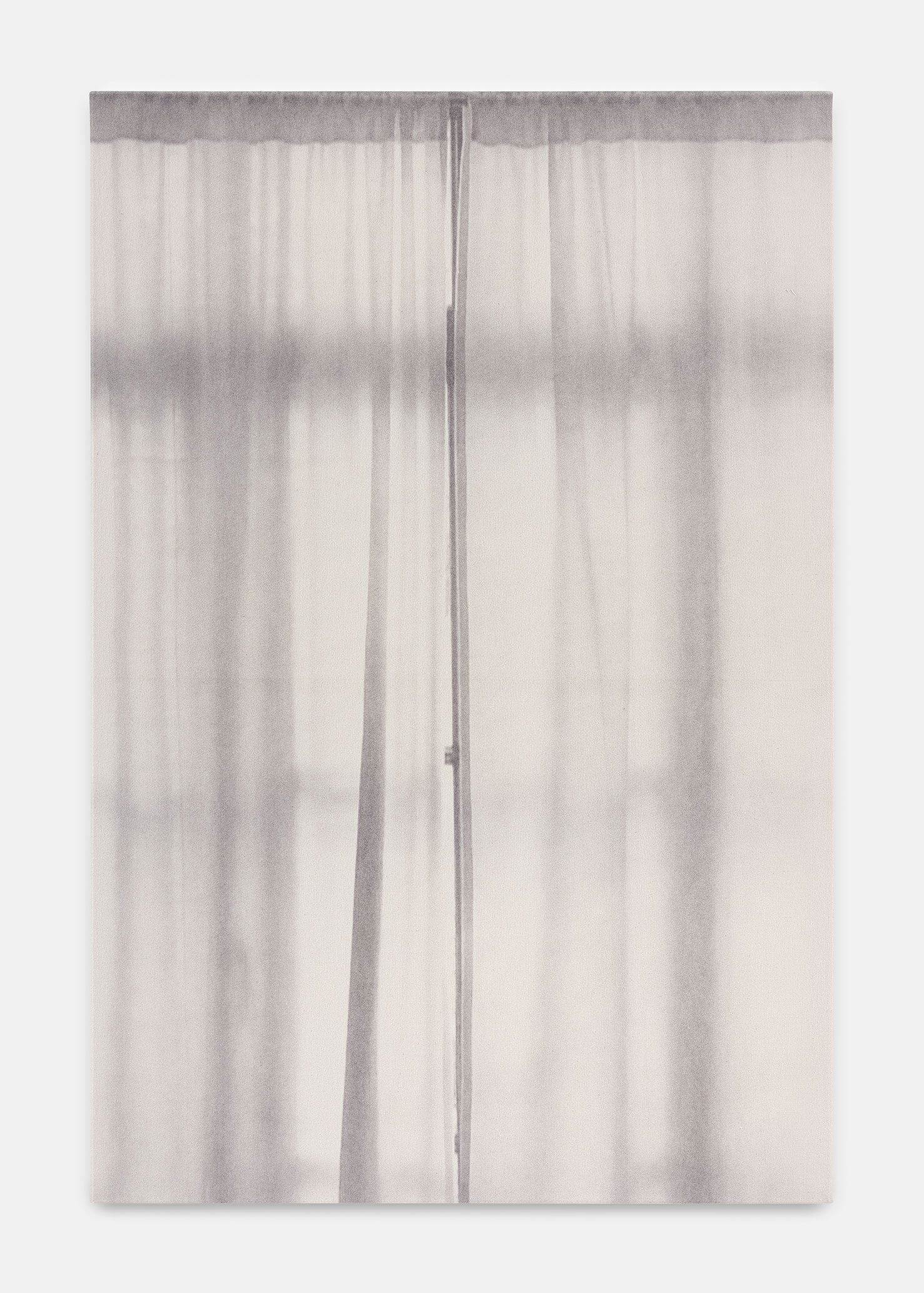

Ziva Drvaric creates spaces that depict the interplay between objects and architecture in a manner reminiscent of still lifes. The absent inhabitants appear to have imprinted their presence on this world of objects, leaving behind an eloquent emptiness. However, by reinterpreting individual elements or altering the appearance of everyday objects, Drvaric casts doubt on how we perceive things and how we compare them to reality. Where the real and the imaginary overlap, our imagination enters the supposedly familiar (but fleeting) reality. Shadows then trace the presence of sunlight that does not (or no longer) shines.

Ziva Drvaric is interested in such thresholds – where inside and outside come into contact with each other, boundaries become diffuse and the subject seeks reassurance about their place in their self-perception. Her subtle interventions in the image and in the space thwart certainties, duplicate what already exists or form echoes of something that does not (or no longer) exist. These works offer psychologised images of our broader sense of home – a place where layers of time overlap and things become extensions of the self – a time-space fold of the self.

Helena Parada Kim, on the other hand, appropriates painterly genres and styles in order to reflect on the associated pictorial traditions and their potential to make the diasporic tangible. As the daughter of a Korean mother and a Spanish father, she incporporates collective and her personal post-migrant history in her work. Her old-masterly-style plant paintings and still lifes are reminiscent of Spanish Baroque painting, but portray East Asian cultivated plants such as the deer-tongue fern or pond lilies, or present ceremonial dishes, the staging of which plays an important role in the Korean culture of commemorating family ancestors.

Here, too, the material is connotatively charged and becomes a trigger for negotiating subjective memory and cultural identity. The ‘nature morte’ of the still life appears in a double sense, spanning time and space, and the screen – arguable one of the most significant element of East Asian art – becomes the carrier for a Europeanised depiction of local pond plants.

Parada Kim selects such plant species based on their distribution and global migration, and then depicts them on a large scale, focusing on their texture and form – precisely because these plants are rarely recognised or considered worthy of depiction.

Her painting of a hanbok, a traditional Korean garment, becomes an evocative portrait of the person who wore it. However, it also raises fundamental questions about geographical home and belonging. The hanbok belonged to someone who immigrated to Germany and is now presented as a handcrafted showpiece in all its painterly splendour. And yet it remains a hybrid artefact, spanning times and cultures.

Vanessa Joan Müller

Vanessa Joan Müller