Mella Jaarsme & Wedhar Riyadi

Rakit

Project Info

- 💙 BEIGE Brussels

- 💚 Tiffany Tang

- 🖤 Mella Jaarsme & Wedhar Riyadi

- 💜 Tiffany Tang

- 💛 Isabelle Arthuis

Share on

Mella Jaarsma_Dogwalk_BEIGE

Advertisement

Mella Jaarsma_Dogwalk_installation view_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Give me your finger, I eat your hand 1_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Harta 3_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_installatio view 3_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_installation view 2_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_installation view 4_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_installation view_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Opposite Heads_shoes III_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Opposite Heads_shoes III_installation view_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Rakus_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Rakus_installation view_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Wedhar Riyadi_installation view_BEIGE

Mella Jaarsma_Wedhar Riyadi_installation view2_BEIGE

Wedhar Riyadi_Marked #7_1 BEIGE

Wedhar Riyadi_Marked #7_BEIGE

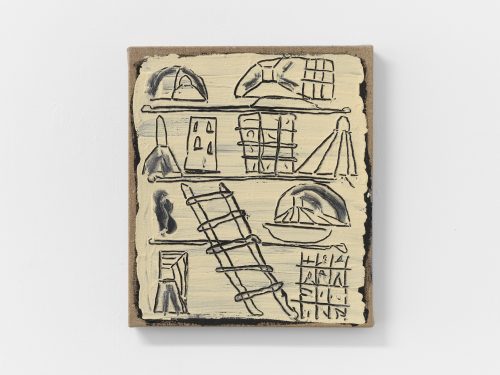

Wedhar Riyadi_The Stack_BEIGE

Wedhar Riyadi_The Stack_installation view_BEIGE

BEIGE is pleased to present Rakit, an exhibition uniting the works of Yogyakarta-based artists Mella

Jaarsma and Wedhar Riyadi, curated by Tiffany Tang. The title Rakit is an Indonesian word meaning

“to assemble” or “to put together”. Through a dialogue among selected works by the two artists,

with particular focus on the notions of the body, assemblage and the performative, the exhibition

illustrates how these concepts unfold within the practices of Jaarsma and Riyadi.

Encompassing installations, videos, drawings, paintings and sculptures, Mella Jaarsma is best known

for her costume installations, designed to be activated by performers, and which address the key

issues in Indonesian culture, its post-colonial histories, and recent socio-political and ecological

developments. The costume set Rakus, which means “greed”, is inspired by the traditional Balinese

mythological figure Rangda, a demon widow queen who has a long, protruding tongue, and is seen as

the personification of evil forces against the leader of good forces, Barong. By borrowing visuals and

narratives of the imaginary, Jaarsma comments on the present-day socio-political situation of greed

and corruption, as well as the political manoeuvres of those in power that recur throughout history.

DogWalk, a video work commissioned for the Sydney Biennale in 2016, is a commentary on how the

relationship and hierarchy of power between human and animals have changed over time as our

societies evolved, and how the artist sees the bond between them as essential and vital. The title is a

parody of the “catwalk”, featuring performers in a parade, donning costumes made of animal skins of

cow, goat and sheep, which are sacrificial animals used during the Eid al-Adha, the “Sacrifice Feast”

in Indonesia.

While pieces of clothing are “put together” when being worn or displayed as wall-based installation,

the work Opposite Heads – shoes III present a floor-based sculpture composed of stacked wooden

feet of varied hues, each topped with a band of goat fur to create a pair of sandals. Visitors are

encouraged to wear them, highlighting the performative and interactive aspect of Jaarsma’s works.

A selection of works on paper is on view in the exhibition, which very often complement a particular

installation, though they are also seen as works in their own right. Jaarsma often incorporates found

materials in her drawings, as another form of assemblage, such as the bamboo fragment in Give me

your finger, I eat your hand I, a work that illustrates the relationship between the body and

architecture, and by extension social space, which is also a common theme in Jaarsma’s oeuvre.

While the concepts of assemblage and the performative are more explicitly exhibited in Jaarsma’s

works, these ideas are inherent in the processes behind Wedhar Riyadi’s pink-palette chiaroscuro

paintings. Riyadi belongs to the generation of artists who was strongly influenced by the political

reform in Indonesia in the 1990s, marked by the fall of the Suharto regime and the subsequent

transition to democracy, which led to a growing influence of Western and Japanese popular culture

in the local media. His works investigate our relationship with digital technology, and how it

influences the notion of representation in the genre of painting, as well as our perception of identity.

Riyadi’s recent series of paintings came about during the pandemic lockdown, when he began to take

inspiration from domestic objects that he could have access to, and assemble them to create a kind

of mise-en-scène. He then replicates the ensemble with the use of clay, a material resembling the

colour of skin and flesh, allowing the artist’s touch to be imprinted on the surface, a gesture that

marks a return to the body during a time of isolation. The objects are then captured and

manipulated digitally to create a contrast of artificial lighting and shadow, rendering the scene a

certain surrealistic undertone. The resulting image is then transposed onto canvas through painting.

In The Stack, the artist assembled a fruit, a lemon, a mug on a base of three sculptural feet, with a

spoon leaning against it, and a twig hanging on the rim of the mug. The totemic stack, which

resembles a human figure, plays with the sense of balance and precarity, while exploiting the

performative aspect of the chosen objects. The painting blurs the perception between natural and

unnatural, still-life and self-portraiture, light and shadow, and is reminiscent of the Dutch vanitas

paintings, which suggests the fragility of human life. Marked #7 features a human bust made of

clay, with its face blurred and concealed by the small lumps of clay. This series relates to Riyadi’s

earlier body of work, where he appropriates and distorts images from the mass media, creating

collaged imagery that explores the psychological depth in our relationship with visual

representations in the digital era.

By bringing together the practices of Mella Jaarsma and Wedhar Riyadi, Rakit proposes assemblage

and the performative as formal strategies through which to examine the notions of the body,

materiality, and image-making. Whether through Jaarsma’s wearable sculptures that are activated

by, and in turn activate social space, or Riyadi’s layered processes of image construction that bridge

the physicality of objects and the digital realm through painting, their works reveal how objects and

performativity serve as strategies to engage with the socio-political and cultural issues that define

our time.

Text by Tiffany Tang

Mella Jaarsma (b. 1960, Emmeloord, the Netherlands. Lives and works in Yogyakarta, Indonesia)

studied visual art at Minerva Academy in Groningen (1978–1984), after which she left the

Netherlands to study at the Art Institute of Jakarta (1984) and at the Indonesian Institute of the Arts

in Yogyakarta (1985–1986). She has lived and worked in Indonesia ever since. In 1988, she co-founded

Cemeti Art House, now called Cemeti Institute for Art & Society, with Nindityo Adipurnomo, one of

the first spaces for contemporary art in Indonesia. She also initiated in 1995, with a group of friends,

the Cemeti Art Foundation, now called the Indonesian Visual Art Archive in Yogyakarta.

Mella Jaarsma’s works have been presented widely in exhibitions and art events in Indonesia and

abroad, including: ‘Videobrasil’, Sao Paolo, Brazil; ‘Biennale Jogja XVI Equator #6’, Jogja National

Museum, Indonesia; (2021); ‘Dunia Dalam Berita’, Macan Museum, Jakarta, Indonesia (2019); ‘The

Setouchi Triennale’, Ibuki Island, Japan (2019), the Thailand Biennale, Krabi (2018); the 20th Sydney

Biennale, Australia (2016). Her work is part of the collection of the National Gallery of Indonesia;

Tumurun Museum, Indonesia; Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, Australia;

The National Gallery of Australia; the Singapore Art Museum and the National Gallery Singapore,

among others.

Wedhar Riyadi (b. 1980, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Lives and works in Yogyakarta, Indonesia) is part of

the generation of artists who was strongly influenced by the political reform in Indonesia in the

1990s, marked by the fall of the Suharto regime and the subsequent transition to democracy, which

brought about a rising influence of Western and Japanese popular culture in the local entertainment.

His works explore our relationship with digital technology, and how it influences the notion of

representation in the genre of painting, as well as our perception of identity.

He has exhibited widely in Asia, Australia, Europe and USA. He participated in the 9th, 10th, and 11th

edition of ARTJOG (2016, 2017, 2018) and in the 7th Asia Pacific Triennale of Contemporary Art (2012).

In addition to numerous private collections worldwide, his works are included in the collections of the

Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, Australia; National Gallery of Victoria, Australia;

Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, Australia; and Tumurun Museum, Indonesia.

Tiffany Tang