Archive

2021

KubaParis

Wohnstatt der Steine

Location

Galerie ConradiDate

09.09 –03.12.2021Photography

Christian NeumeisterText

Suse Bauer

Wohnstatt der Steine

Conradi

September–December 2021

e

In your new exhibition, three skewed plinths with undulating profiles draw the visitor’s attention. The exhibits displayed on them might be sculptures, but they also read as models. Compared to the sharp-edged plinths, their surfaces seem raw and porous. Are these submissions to an art-in-architecture contest? Or are they inchoate modernist architectural visions, perhaps meant for transposition into a different scale, to a different place …? Wohnstatt der Steine, Abode of the Stones—the title seems to suggest as much.

s

In my imagination, I conceived them as models of monumental structures, with a forbiddingly compact and vaguely oppressive aura. I thought it was key to leave the scale and function undetermined. I made Wohnstatt der Steine in 2019, after an extended trip to Israel. I looked at the brutalist architecture all over that country because I was interested in the urbanistic formal vocabulary of what was once a society of pioneers and in particular because of what I see as parallels to the formal idiom of East German architecture. The difference being that the Israelis made much more extensive use of concrete, which stands there in that insane heat. I’m curious about how people envision the future. So I took sculptor’s clay, which when wet is reminiscent of washed concrete or very rough rendering, and rolled it into slabs, which later turned into these sculptures.

e

I think of Wohnstatt der Steine as design drawings from archives translated into a plastic medium. For buildings that were never realized. Because the times and situations changed before they could be, or because realization proved illusory or hubristic.

s

I’m interested in the socialist large-scale construction project as an image and stage in two works of literature in which it becomes a screen on which the failure of a utopian vision hobbled by hierarchies and bureaucratic institutionalization plays out. The novel “Trace of Stones,”1 which came out in East Germany in 1964, supplied Heiner Müller with motifs for his play “The Construction Site,”2 written that same year. Müller himself described his play, which was barred from publication until 1980, as being “about how the utopia ravages the landscape.” Andrei Platonov’s novel “The Foundation Pit, 3 completed in 1930, was not published until 1987 due to censorship. It tells the story of a gigantic proletarian construction project that aspires to build nothing less than a future of happiness for humankind; to be achieved by universal collaboration and manual labor, it founders under the burden of its purpose.

e

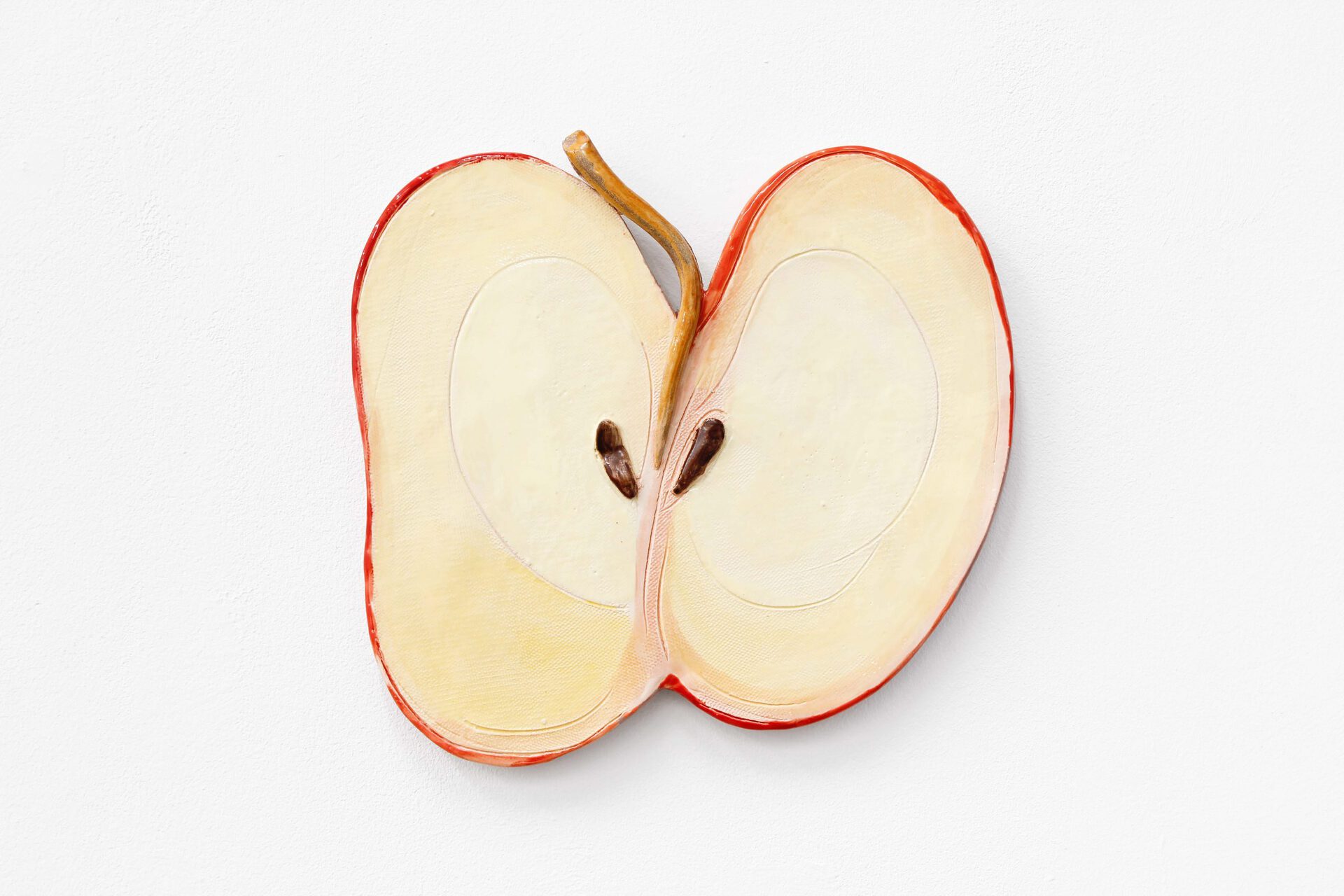

Your works in many ways play on dimensionality, polysemy, and latency. The same, for that matter, is true of the Makers and Takers—the oversized and oddly distorted ceramic coins or apple slices on the showroom’s walls. Relations of scale feel simulated and negotiable. Everything lingers in a status of conditional validity, awaiting the next update. Perhaps this unfinished and preliminary quality is also one explanation for why the clay objects in Wohnstatt der Steine were fired only once, without the final glost firing that sets the material’s form?

s

I prefer the term constructions, and yes, that’s true. These constructions are possibilities, being preliminary is part of their nature, they are frozen in a state of nascency.

e

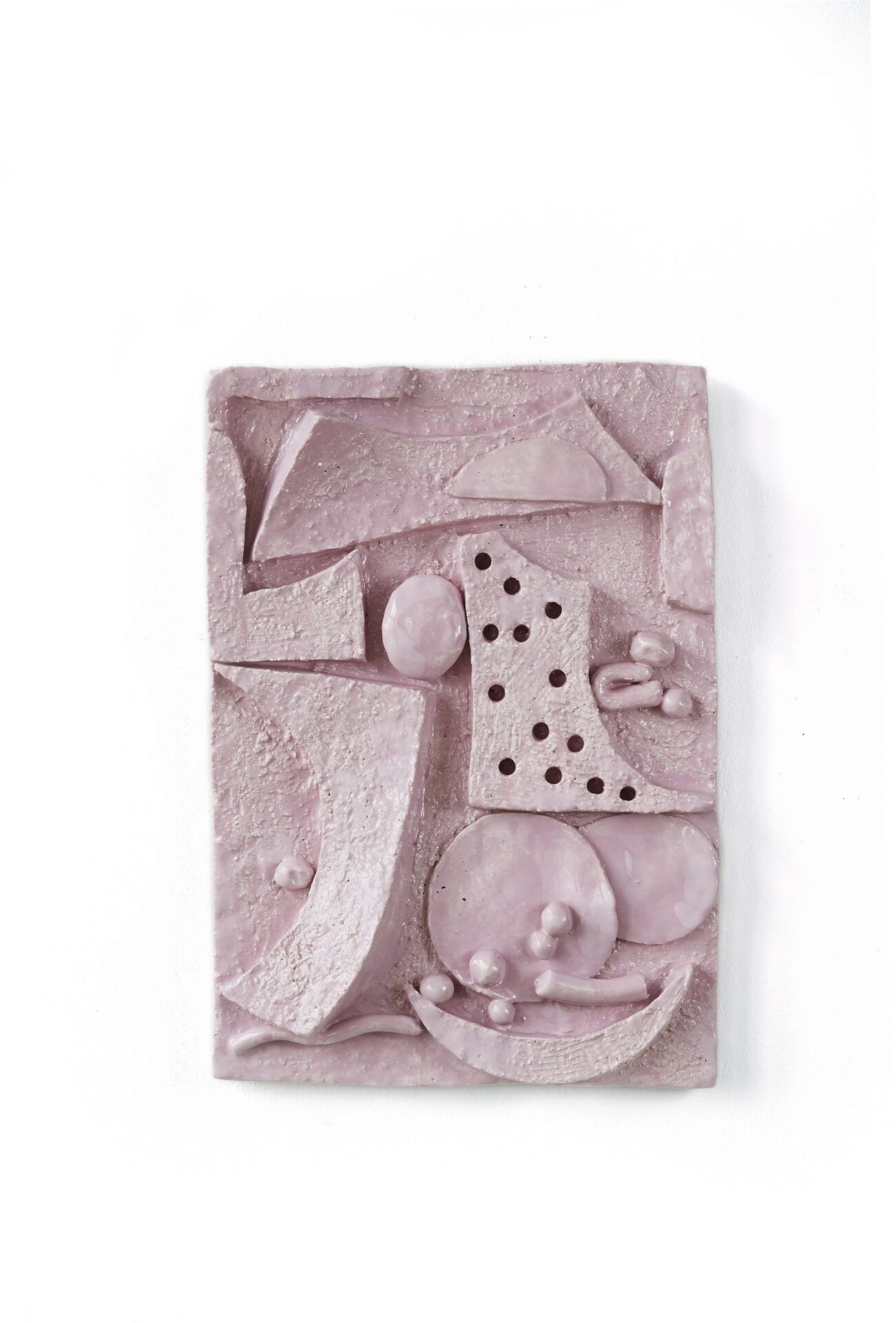

Constructions, then. Another ceramic work in the exhibition—a relief-like wall piece made of glazed clay—is titled Wohnscheibe (Residential Slab Block), a recognizable allusion to generic prefabricated housing structures in East Germany. Wohnstatt der Steine, by contrast, is an artistic exploration of the idea of architecture as a political vision. The buildings of industrial modernity with their aesthetic and functional standardization of architectures reflect a social compact that subordinates the singular to the common good. Then, with the fall of the Wall, the associative framework around construction sites shifted. Residential living cast in concrete nowadays satisfies urban elites’ need to signal distinctiveness.

s

The (prefabricated) housing estate figured prominently in my parents’ personal lives and careers: both were civil engineers and worked in slab prefabrication. The apartment on the periphery they moved into with us children in 1980 was modern, in contrast with the derelict old city center. Everything looked the same, so we painted our balcony in colors. That way, I could point out where we lived to my friends from the playground. The insides of these residential slab blocks then accommodated the ‘new man’ with his individual desires in terms of interior design: wood paneling, wall-size Caribbean-beach poster, cuckoo clock. Later on, my childhood was also set on the building sites of the reunification era; my parents started a construction company and, in 1991, moved us into central Erfurt. The renovations that were proceeding apace all around us are now complete: the city has a neatly restored medieval center. The prefabricated housing estates have been partly “unbuilt” and, especially in the periphery, have become scenes of the social tensions prompted by the societal fractures of the “East German society-in-transformation.”

e

The title sounds programmatic, bringing utopistic statist housing and urban planning conceptions to mind: Abode of Stones might be a working title for a major design contest for new public facilities, buildings or monuments, making your show a presentation of the winning submissions.

s

Yes, but I think there’s an ambivalence, even an edge of sadness. These stones, they are, well, petrified, fixed. The only thing they may yet become is dust. When I meditate on the title, I see a devastated landscape.

Conversation between Suse Bauer and Elena Conradi

Erik Neutsch, Spur der Steine, Halle: Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 1964.

Heiner Müller, Der Bau (1964), 2018.

Andrei Platonov, The Foundation Pit (1930/1987), New York Review of Books 2009.

Steffen Mau, Lütten Klein, Suhrkamp 2020.