Archive

2021

KubaParis

The Cabinet of Ramon Haze

Location

Galeria SKALADate

03.12 –27.02.2022Curator

Jakub BąkPhotography

Galeria SKALASubheadline

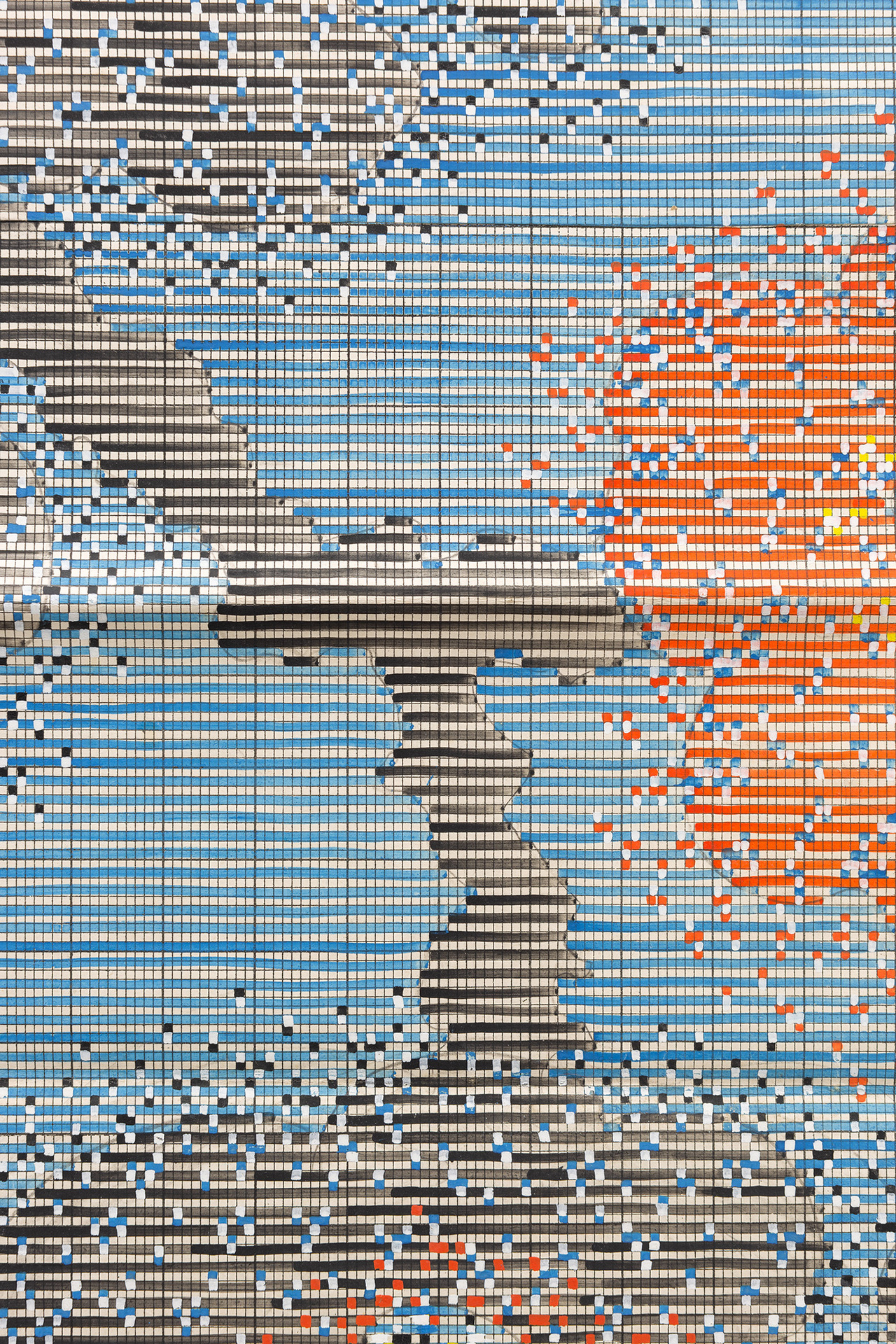

Ramon Haze is a detective and art collector who will live in the future. On his commission, Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl acquire, conserve and catalogue artefacts that reflect his ideas about the most important works of art of our era. Ramon Haze’s collection comprises the most valuable saved objects from some of the best artists, including: Marcel Duchamp, Jeff Koons, Andreas Bader, Ilja Kabakov, Daniel Burren, Charlotte von Schmerder-Kutzschmann, Ruth Tauer, Piero Manzoni, Josef Scharlamann, Jonald Dudd, Franz Erhard Walther, Constantin Brâncusi, or the completely forgotten Edward Baranov-Knepp.Text

Ramon Haze is a detective and art collector who will live in the future. On his commission, Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl acquire, conserve and catalogue artefacts that reflect his ideas about the most important works of art of our era. Ramon Haze’s collection comprises the most valuable saved objects from some of the best artists, including: Marcel Duchamp, Jeff Koons, Andreas Bader, Ilja Kabakov, Daniel Burren, Charlotte von Schmerder-Kutzschmann, Ruth Tauer, Piero Manzoni, Josef Scharlamann, Jonald Dudd, Franz Erhard Walther, Constantin Brâncusi, or the completely forgotten Edward Baranov-Knepp.

The first display of the works collected on behalf of the fictional collector took place in the basement of an abandoned factory in Leipzig, where Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl lived, during their studies in the mid 1990s. The moment the “East” ceased to exist, almost all of its material and cultural heritage fell into oblivion. Objects devoid of both a function and a symbolic sense became a reservoir of potential artistry and were used to develop a multi-threaded, ironic story in the form of a private collection. A fantastic production, which in terms of aesthetics is in no way inferior to prestigious institutional exhibitions, is also a perverse criticism. What comes to the fore here is the arbitrariness, discursiveness and materiality of the works of art, but also consumption, pure potentiality and total fortuitousness.

More than two decades after the first exhibition, the collection and the idea behind it have yet again become topical. Late capitalist societies have been sharply awakened from the dream of the end of history and the universal paradise of unrestrained consumption. The battlefield that shadows development emerges on the surface, and the end, which is looming on the horizon becomes ever more real. Feldmann and Grahl are, in a way, also characters from the future, only somewhat more real to us than the hazy Haze. From their perspective, our entire world is both rubble and treasure, full of rubbish and priceless works of art, which all compete to be named as the crowning achievements of their time. When the threat of catastrophe looms over us, this constructed way of seeing becomes meaningful, and the kind of serious sense of humour that comes with it seems particularly attractive.

JAKUB BĄK

“My name is Ramon Haze and you could say I’m an art detective. The exhibition at the SKALA gallery in Poznań shows the art of the 20th and 21st centuries as I managed to save it. Over the last thirty years, in my cabinet I have accumulated a collection of the most valuable works of art by the best artists of the time. Back then, art meant a discipline of research in which thoughts and feelings, visions and knowledge of all kinds were expressed in more or less specific objects. The artistic way of perceiving and presenting allowed their creators to show things in a different light. The importance of art has been intensely debated. The broadest arguments and the farthest examples were used in attempts to define its role, nature and possibilities, which resulted in the emergence of a field of hugely diverse practices. Reconstructing ancient artistic culture requires diligence and passion. A single work was very often the impetus for me to conduct a large-scale investigation. To learn more about a bygone era, I explored deeper and deeper areas, going layer by layer, as far as I could. In these activities, I have often lost touch with my own present. I identified with my artists and dug until I got to the essence of their being. In my investigations, I circled over the buried world of ideas in which concepts such as creativity, work, context and ready-made regularly appeared.

My cabinet currently contains 260 works by 24 artists, and 22 works whose authorship has not yet been attributed. All my efforts and their effects, including those that can be seen in this exhibition, are a record of a certain state of affairs, the current stage of my unfinished pursuits, open to comments and discussions.

Special words of appreciation and thanks are deserved by my tireless agents Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl, who persistently, and often daringly work on the conservation, preservation and expansion of the collection”.

RAMON HAZE

EVERYTHING IN THIS COLLECTION IS ART Holmer Feldmann in conversation with Agnieszka Kilian

A.K.: Could you please tell us about “The Cabinet of Ramon Haze”? I am curious about the way you talk about this project from today’s perspective.

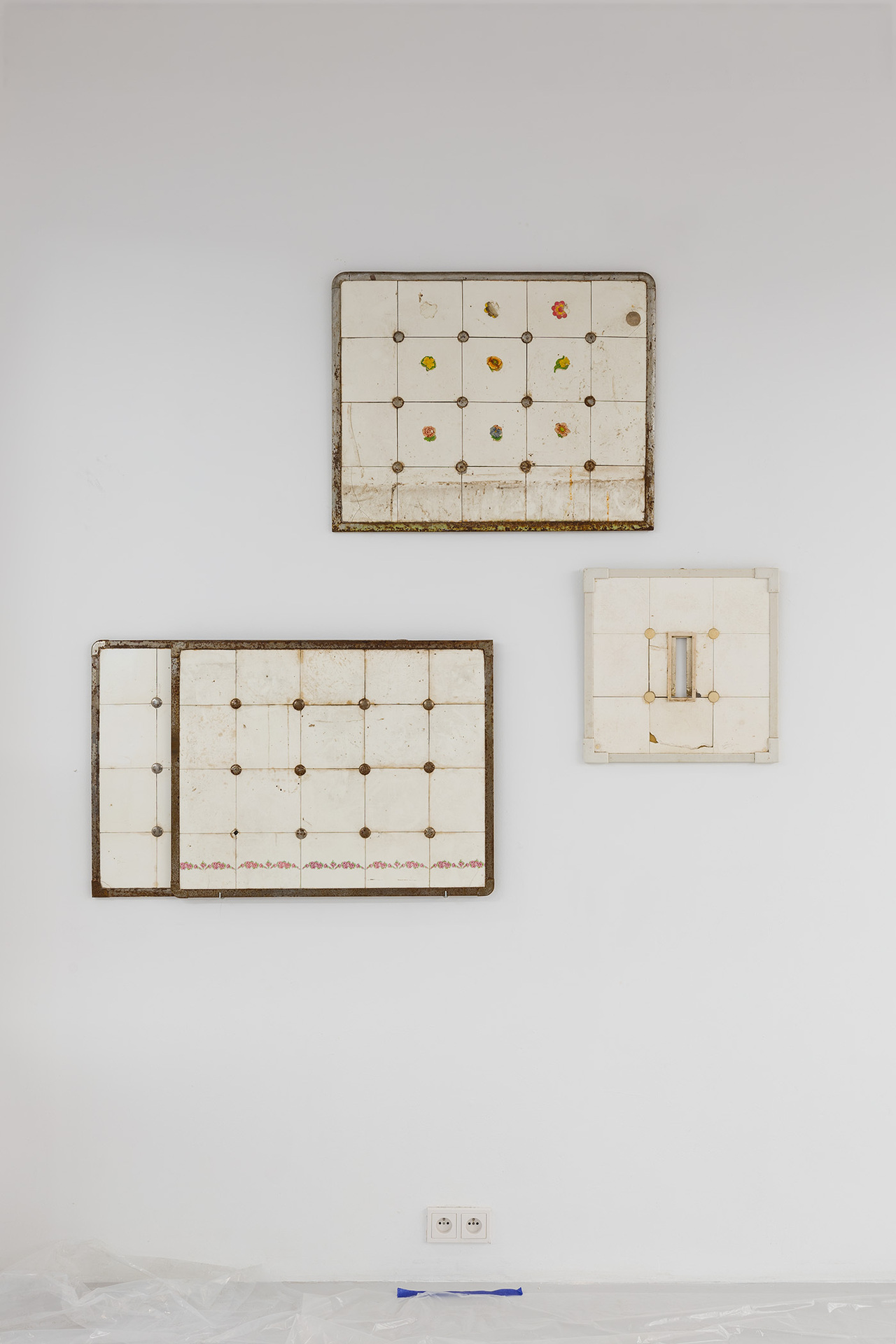

H.F.: I’ve been doing the Cabinet with Andreas [Andreas Grahl – A.K.] since around the mid-1990s. It was then that we started accumulating things that we did not know what they were. They could be found any time and everywhere. Many of them had been abandoned (and still are!). When the first room was already full we started wondering: what are we going to do about it? And since we are artists, it was clear that it had to be art. Then we began to classify the finds according to time and space.

Who is Ramon Haze?

Ramon Haze lives in an age whose culture follows ours. It is from this position that he collects 20th and early 21st century art. We once lived with him for a very short time, but he was, as the name suggests, a hazy apparition.

Is fiction your method? Do you think that fiction is something given, ready, or rather worked out?

I would challenge the use of the word itself – these things do exist. Fiction intersects with reality, becomes it in a way. I would prefer to use the word narrative. But for us, everything was, and is, art. Our activities can be compared to archaeologists and their work. They have clues, knowledge, so they dig and hope to find something. But ultimately what you dig also depends on chance... The find is fortuitous, but it is not always easily attributable. For some works, it was quite easy to identify the authors. Source references were readable and did not allow other conclusions, such as objects in the collection attributed to Marcel Duchamp, Ilya Kabakov or Jeff Koons. Inter- nationally renowned names, many of whose works are known. With some of the other ones it was more difficult...

So if we consider attribution as part of your method, it is worth returning in this context to the moment of finding the objects assigned to Marcel Duchamp. According to you, the urinals were deposited in Dresden in 1912. And it’s a fact Duchamp was in Dresden at the time. However, as an art object, “Fountain” was not presented until 1917...

Showing the urinal at the exhibition as a work of art was a scandal at the time. The “original”, which was not allowed to be presented at the “Society of Independent Artists” exhibition, was lost. The copies we know today were reproduced by a gallery in Milan in the early 1960s. So they were copies, but that didn’t matter to Duchamp and his ideas. However, the “original of the original” was created and kept in Dresden. Then, during the First World War, he went on a journey; in 1915 he moved to New York. The First World War ended, the turbulent period began, the Second World War began, and finally Germany was divided. Duchamp was not able to come back to secure the works. Commercial Coordination (Kommerzielle Koordinierung) –“KoKo” for short – a large corporate network founded in the GDR by Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, spared no resources to obtain a form of foreign currency for the GDR. When KoKo tried to sell fountains on the international art market and Duchamp found out about it, he commissioned and authorized a few copies of the urinal. In this way, the urinals belonging to KoKo became primitive fakes and could no longer be sold.

We’ve talked about the fact that assignment is not without intention. I’d like to ask about this perversely: if the owner of the collection, Ramon, were Ramona, a woman, wouldn’t she have noticed Baroness Elsa von Freytag instead of Marcel Duchamp?

I don’t know her...

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was a Dadaist poet and artist. She had lived in New York City since 1910, and when Marcel Duchamp came to New York, they became friends. There is a theory propounded by, among others, Siri Hustvedt, that it was the Baroness who supposedly give Duchamp the idea of the “Fountain”.

I had no idea about it...

How about the case of the story of urinals deposited in the GDR, was it important for you to pay attention to the history of art inspired by the West?

No. East and West are irrelevant to us. I am from West Germany and Andreas from East Germany. We met by chance at university. Plus, quite by accident, after many years, we lived in a factory together, and then we created this work.

You are narrating “from the future”. Is your narrative complete or is it evolving?

It is not closed, because it is a living collection. The exhibits are also removed from the collection, e.g. if they do not retain their artistic character after many years. They are no longer on display. One of them was created by Ferdinand Porsche.

I wanted to ask about this - about his “Trabi”, the Trabant.

Porsche’s works or models are not art. This is design, very good design. But at the same time, it is nothing but design, so we decided not to show it anymore. Although it is illustrated in the catalogue, it is no longer part of the collection. Besides, the book with the catalogue raisonné is in fact a conceptual work in itself. It includes illustrations and corresponding texts. The updated edition mainly contains photos of recent works and installations. The list provides information on whether items are still in the collection or if they have been removed. However, for conceptual reasons, the catalogue itself remains in its original form.

This tension between the collection and the catalogue is an interesting one. Is this division into fine and applied arts clear for you? Or is there an example of an object where this division was not so straightforward?

Everything in this collection is art. Nothing greater or lesser than art.

There is also a work by Franz Erhard Walther in your collection. He developed a very unique approach to work and action. He said: “This idea has fascinated me all my life: that a work can be accompanied by an action and, consequently, that the action itself takes on the character of a work”1. And what do work and action mean to you? When does an action become a work of art?

There is a problem with Walther’s works. They were created with the intention of using and activating them. A museum exhibition does not lend itself to the objects being used by visitors.

Do you know his suits that can be worn in pairs? [this pertains to the work entitled “Dreizehn Handlungsformen” – A.K.]? An owner of a private collection can invite their guests to play and say: let’s put them on! In the case of an art exhibition, the work locked in a showcase does not function, so it is dead. Our collection includes “Kopfarbeit” [Trans. “Head action”]. Three years ago we were in Mönchengladbach in a sushi restaurant just around the corner from the Abteiberg museum. We found the originals of Walther’s work in the men’s restroom. It was a board to lean your head against the wall next to the urinal. A simple fabric or fake leather cushion on a wooden board, simply mounted on the wall. Subsequently, we asked for and obtained permission to take the slightly worn-out, used items from the 1980s from the place of operation to include them in the collection. And we have placed a replica in their place so that they can continue to be used.

1) „Diese Vorstellung hat mich ein Leben lang fasziniert: dass zu einem Werk Handlung kommen könnte. Mit der Konsequenz, dass die Handlung selbst Werkcharakter bekommt”. Franz Erhard Walther in an interview for Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin 19/2018.

A great story about changing the function.

Replicas – fresh, the same size, beautifully made – remained “in action”. The originals found their way to us – and they can no longer be used, especially if the collection is shown in a museum context.

During the exhibition in Mönchengladbach, you invited students to suggest different attributes of objects, offer their alternative stories. The perspective of never-ending circulation - disassembling various elements of the story and then reconfiguring them – seems to me to be particularly important for this collection. This idea came from observing and experiencing the horror of a guided tour of a museum: you are shown around the halls and forcefed information, and in the end you are left with nothing of your own. During the first presentation in Leipzig, we invited theatre academy students to conduct a guided tour – they had a (somewhat controlled) freedom of interpretation, and sometimes invented amazing stories. Nobody from the audience questioned the competences of the guides. It was and is about conveying this possibility of interpretation. With some objects it is difficult to come up with something entirely new as in the case of Duchamp and his “Fountain”, or Brancusi and the model of the “Endless Column”. In the case of other items, the scope of innovation is much greater. Thanks to this, the collection becomes alive.

Were there any differences between your interpretation and the interpretations suggested by the students?

A film was made during the tour in Leipzig. It will be shown in Poznań. It includes amazing ways of storytelling and interpretation.

Are you going to show your new works in Poznań?

Every time we work intensively on a new installation, new works appear In Poznan we will show a piece that has not been exhibited before, and its title has not yet been determined. Research to date attributes its authorship to Jonald Dudd. A second new work developed itself during the set up. It is a site-specific work covering the complete floor under all the artworks of the exhibition and is called “Borderline-complex”. The author is unknown.

HOLMER FELDMANN was born in 1967 in Neumünster (Schleswig-Holstein). He studied photography and visual arts at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig. He is a founder of an arts association in Buscha/ Thüringen. He splits his time between Berlin and Buscha.

ANDREAS GRAHL was born in 1964 and grew up in East Berlin. He studied photography at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig and at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana (The University of Arts of Cuba). He teaches photography at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig.

Jakub Bąk, Ramon Haze, Agnieszka Kilian, Holmer Feldmann