Archive

2020

KubaParis

The Skull of the Haunted Snail

Location

HangarDate

24.09 –20.11.2020Curator

Bruno LeitãoPhotography

Bruno LopesSubheadline

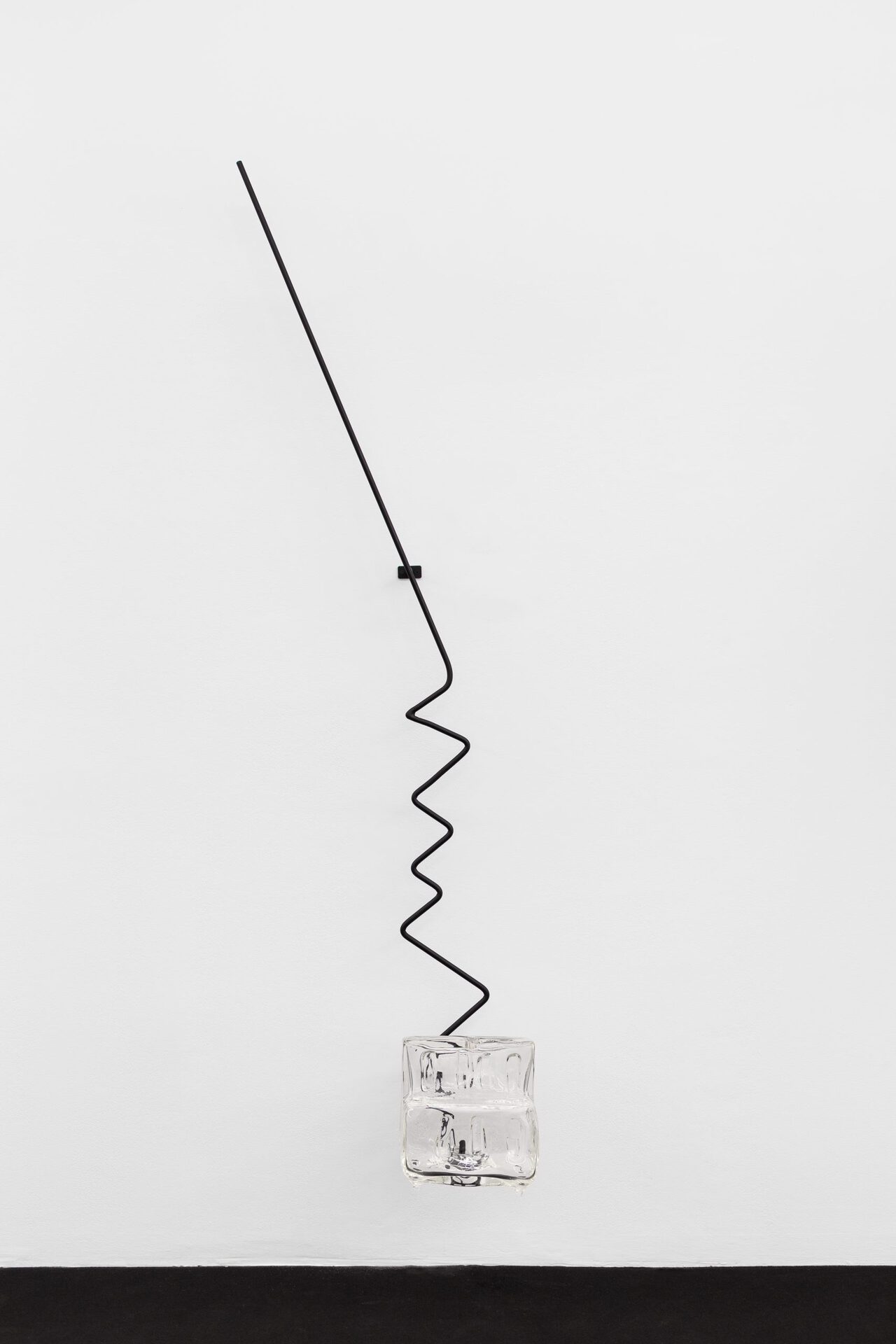

The exhibition ‘The Skull of the Haunted Snail’ by Andreia Santana (Lisbon, 1991), curated by Bruno Leitão, is part of the regular program of the exhibition space Hangar – Centro de Investigação Artística, in Lisbon, and is the result of Andreia Santana’s artistic research on the “Soul Houses” of Ancient Egypt as a practice and materialization of an object that is simultaneously an ecosystem, and an interface. Through an installation of glass sculptures conceived specifically for this exhibition, Santana intends to examine the condition of the artefact as a shelter, which enables the growth of other organisms (be they pests, bacteria or fungi), thereby modifying its museological status and decontextualizing it from its function as a historical artefact to host and sustain other types of existence and species in the future. Santana, by proposing a counterpoint with the concept of Wittgenstein’s glass fly traps and Donna Harraway’s sympoiesis suggests the belief that artifacts, objects, places, living beings and entities – and, consequently, history itself – must be perceived as a potentially animated and living material that possesses a distinct spiritual essence (exactly as the Egyptians saw it), to the detriment of a stagnated gaze on obsolete knowledge and objects preserved in an interpretative vacuum. In ‘The Skull of the Haunted Snail’, the visitor is invited to reflect on the artifacts as persistently contemporary forces that allow other intersectional forms of solidarity and contamination of time and space to appear, revealing new substances, matter, objects and bacteria as new possibilities of understanding history, culture and interspecies coexistence are spread.Text

Don't think, look!

The Skull of the Haunted Snail

Andreia Santana

It is evident that man's shadow is similar to him: his mirrored image. Rain, thunder, moon phases, changing seasons, the way animals are similar and different from each other and from man, the phenomenon of death, birth and sex life, in short, everything we observe around us year after year in such different ways, plays a role in their thinking (in their philosophy) and practices, or is precisely what we truly know and find interesting.

How could fire, or its resemblance to the sun, not have made an impression on the awakening of the human spirit?

Wittgenstein, L., “Bemerkungen uber Frazer’s Golden Bough” (1931 / 1948) in Philosophical Occasions, ed. James Klagge, Alfred Nordmann, Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis & Cambridge, 1993, pp. 115-155

Santana's work has often been associated with a certain idea of anthropology that characterizes, fundamentally, the way in which the artist starts from an important relationship with objects to develop a point of view that does not reduce them to simple commodities, but recognizes in them different forms of life and different modes of life’s resistance.

It is a kind of anthropology that does not aim to explain the origins, nor to identify causes that are supposed to underlie certain human behaviors, their beliefs or the way certain communities organize themselves, but an action that should be understood as a way to surprise some potentially inscribed stories inside some objects stored in our homes or in museum's archives.

In this sense, it is not a matter of meeting elements with more or less exotic or surprising narratives and origins - which the artist would appropriate to create new works - but of finding the history that things can tell when freed from the dominant and official narratives that tend to encapsulate objects, images, words, in a certain sense, chronology, style or a specific function.

Therefore, I understand that we can look at Andreia Santana's work as the development of a careful ethnography, which is, as a participative and active observation that never creates the illusion from a transparent point of view, without interferences or apodictic observations, identifying an ambition that does not intend to demonstrate authenticity. On the contrary, what is at stake

here is a certain idea of ethnography (especially in view of the method introduced by Bronisław Malinowski) that comprises the continued existence of the subject who observes near objects or communities and wants to understand, watch and learn. It is a question of thinking that only from this intimate relationship with the other - be it a subject, a collective or an object - can some kind of pertinent understanding be generated. And it is precisely in this intimacy that Santana seeks and then reconstructs through her artistic practice.

In addition to the methodological questions at stake here, which aim to bring her artistic practice closer to a certain idea of ethnography, many authors and artists could be brought together who, from Hal Foster's text The Artist as Etnographer?, have found an important field of work in the approach between ethnographic practice and artistic practice. Many of them, in different disciplines and using different media, were nourished by the ambition of a realistic art and moved by the will to reconstruct certain realities, culminating with the approximation of art to the social reality that artists so much wanted to alter, subvert and transform.

In Andreia Santana's work there is no realistic impulse, nor are her sculptures intended to illustrate, solve or explore cultural reality, and her ethnography has no pretensions to address the social, but to concrete and individual things. In this sense, the objects that the artist encounters do not serve as devices for reading a sociocultural reality, but exist as a path for understanding each of these elements in their uniqueness, digging space for their own history and for the different forms of life that each thing has inscribed in it.

It is worth noticing that many of the works of the artist are also critical approaches to a certain idea of archive. Not because this is a resonant subject or because the artist has been taken by the archival fever - to use Derrida's expression "Mal d'Archive", later used by Okwui Enwezor in The Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art - but because she is interested in understanding the logical materials inherent to their construction. In other words, her concern is not related to the epistemological criteria that underlie the creation of the archives, but to the reasons that lead certain material realities to appear and disappear. I emphasize, Andreia Santana's artistic practice does not focus on the politics of the archives or museums, but on what the objects potentially contain beyond the narratives that supposedly illustrate and sensitize them.

The Skull of the Haunted Snail exhibition is precisely in this condition. On one hand, it is based on a collection of terracotta sculptures that the artist found at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, but at the same time the exhibition is about transparency, lightness, depth and about the visual nature of bodies and the body-soul relationship.

All concepts and ideas that the artist approaches critically and poetically.

The starting point is a set of Egyptian sculptures discovered in the 19th century by Ernesto Schiaparelli and which have the suggestive title of Soul Houses. Funerary sculptures that, besides highlighting the mortuary graves, express the way the Egyptians prepared themselves for the life that culminates and is completed with death. These Soul Houses were a sort of offering trays where the family of the deceased placed the necessary supplies for their postmortem comfort. The architectural qualities of these religious sculptures, since they served a certain cult, are to be noted. They are literally housing complexes with all the private and public areas that the Egyptian houses usually comprised. They are artifacts that started and contributed to the formation of an ecosystem where alive and deceased, human beings and other species; liquid life forms, etc. coexist.

The artist's approach to these houses becomes particularly critical as it reminds us that, much more than the literality of the narrative presented and its representative and symbolic power, all other beings bind themselves to them (and have been lodged throughout their long history): fungi, parasites, etc., but also all those heterodox elements that constitute them.

For Santana "artifacts, objects, places, living beings and entities - and, consequently, history itself - should be seen as potentially animated and living material that possesses a distinct spiritual essence (just as the Egyptians saw them), to the detriment of a stagnated gaze on obsolete knowledge and objects preserved in an interpretative vacuum”.

Together with this conception, we must also pay attention to how the artist relates not only to the formal aspects of the sculptures she encountered, but also to how she deals with the metaphysical and transcendental elements contained in them. According to Andreia Santana, this idea arises not through the ritualistic use to be made of these objects, but through the way glass and its qualities of transparency and immateriality allow an effective approach to a certain metaphysical idea.

I would like to underline that the matter of transparency is decisive, because it shows us that the old notion of a soul within a body that animates is a prejudice that must be overcome. And with it, all the dualistic regimes of thought that introduce us to divisions between interior / exterior.

In this context, we can think of Wittgenstein not only because he is a philosopher close to the artist and this project specifically, but also because perhaps no other western philosopher has insisted so vehemently and continuously on denouncing the prejudice of interiority, demonstrating the need to reverse the usual way of thinking and give conceptual priority to the exterior. The philosopher expressed this priority countless times when in his writings and notes he made philosophical pleadings such as "don't think, look!" or as when he declared "the best image of the human soul is the body. And this outward look, which the philosopher transformed into a very particular philosophical heuristic, is a view close to the ethnographic gaze and has in the attempts to describe the material events of the world its greatest ambition.

We are confronted with an appeal to the exterior that has the most immediate consequence of replacing all explanations with precise and attentive descriptions of the material world. Since it is in the exteriority of bodies, things, plants, and everything around us that we can find the answer to the questions that incessantly torment us. It is a question of a thought developed from the conviction that nothing is hidden, and what is required of us is a discipline of looking and attention in order to perceive how, for example, mind and soul are not, as Wittgenstein says, a kind of beetle hidden in a box. Or, continuing with Wittgenstein, to perceive how the entanglements and misunderstandings we' re held hostage of are a prison from which we will free ourselves if we change the focus of our gaze: we' re a kind of fly trapped in a transparent glass bottle and the task of philosophy is to show the fly the way out of the bottle.

Here, a bottle means a fly swatter. These ‘prison-bottles’ are common devices to hunt flies due to their positive phototaxis when strongly attracted by the light and that, even having two holes that allow free circulation, they get stuck in these devices simply because they don't turn their eyes (which is the most powerful form of attention) in another direction. This metaphor serves us to understand that the ‘prison’ where we sometimes find ourselves confined are actually open prisons and that the recognition of openness, that is, of our freedom, depends on an operation as simple as diverting one's gaze and directing one's attention in another direction.

Getting out of these open prisons corresponds not only to a philosophical quest that leads to the achievement of new forms of understanding and perspective, but also to an artistic journey. Not because art can literally save us, but because the exercise of attention that is proposed to us corresponds to an expansion of concentration and comprehension. And because from this experience we perceive that we form community not only with others like us, but also with all the entities different from us. The excerpt that begins this text shows precisely this condition of ours that we are not only identical to other animals, but also to the phenomena that surround us, and for this reason they compose our web of thoughts.

That this mesh is composed of rain and thunder, all phases of the moon, changing seasons, all animals, the phenomenon of death, birth and sex life, etc., does not show a set of things that simply surround us without substantially affecting our subjectivity, that is, external events, but that is precisely what we know. Therefore, we owe attention to all those things and events, and doing art is the most exemplary exercise of attention to the material world.

There would be much more to investigate about the importance of the material world and how the so-called epistemologies of the south (cf. Boaventura Sousa Santos), by directing their knowledge towards these phenomena, manage in an exemplary way to overcome the Western embarrassment of the apparently insuperable dichotomy between interior / exterior, inside / outside, soul / body, human / nature.

When I began by stating that Andreia Santana's work has in certain anthropology an important point of contact I wanted to point out, not a simple disciplinary and inspirational approach, but the way in which her creative dynamics generates a space where all these principles and thoughts converge. In all her ideas, forms and materialities, her work contributes to the expansion of the field of what we can experience and think.

Nuno Crespo

Nuno Crespo