Archive

2021

KubaParis

They call me Gypsy but that’s not my name

Location

Gdańsk City Gallery 2 and Gdańsk City Gallery 1Date

15.07 –25.09.2021Curator

Anna BatkoPhotography

Bartosz Górka / Paweł WylągSubheadline

Dates: July 16 - September 26 Opening: July 16, 6 p.m. - 9 p.m. Venue: Gdańsk City Gallery 1 (GGM1), Piwna 27/29 Street, Gdańsk Gdańsk City Gallery 2 (GGM2), Powroźnicza 13/15 Street, Gdańsk Curator: Ania Batko Artists: Tomasz Armada, Olaf Brzeski, Ewa Ciepielewska, Andrzej Onegin Dąbrowski, Wojciech Fangor, Jerzy Flisak, Krzysztof Gil, Zuza Golińska, Günter Grass, Władysław Hasior, Marcin Janusz, Kunegunda Jeżowska, Stanisław Kałuziak, Tadeusz Kantor, Leszek Knaflewski, Edgar Kovats, Ignacy Krieger, Dawid Mazur, Jan Młodożeniec, Joanna Piotrowska, Tadeusz Rolke, Stanisław Rychlicki, Adam Rzepecki, Walery Rzewuski, Feliks Sadowski Feliko, Slavs and Tatars, Janek Simon, Aleksander Sovtysik, Stanisław Witkiewicz, Paulina Włostowska, Stanisław ZamecznikText

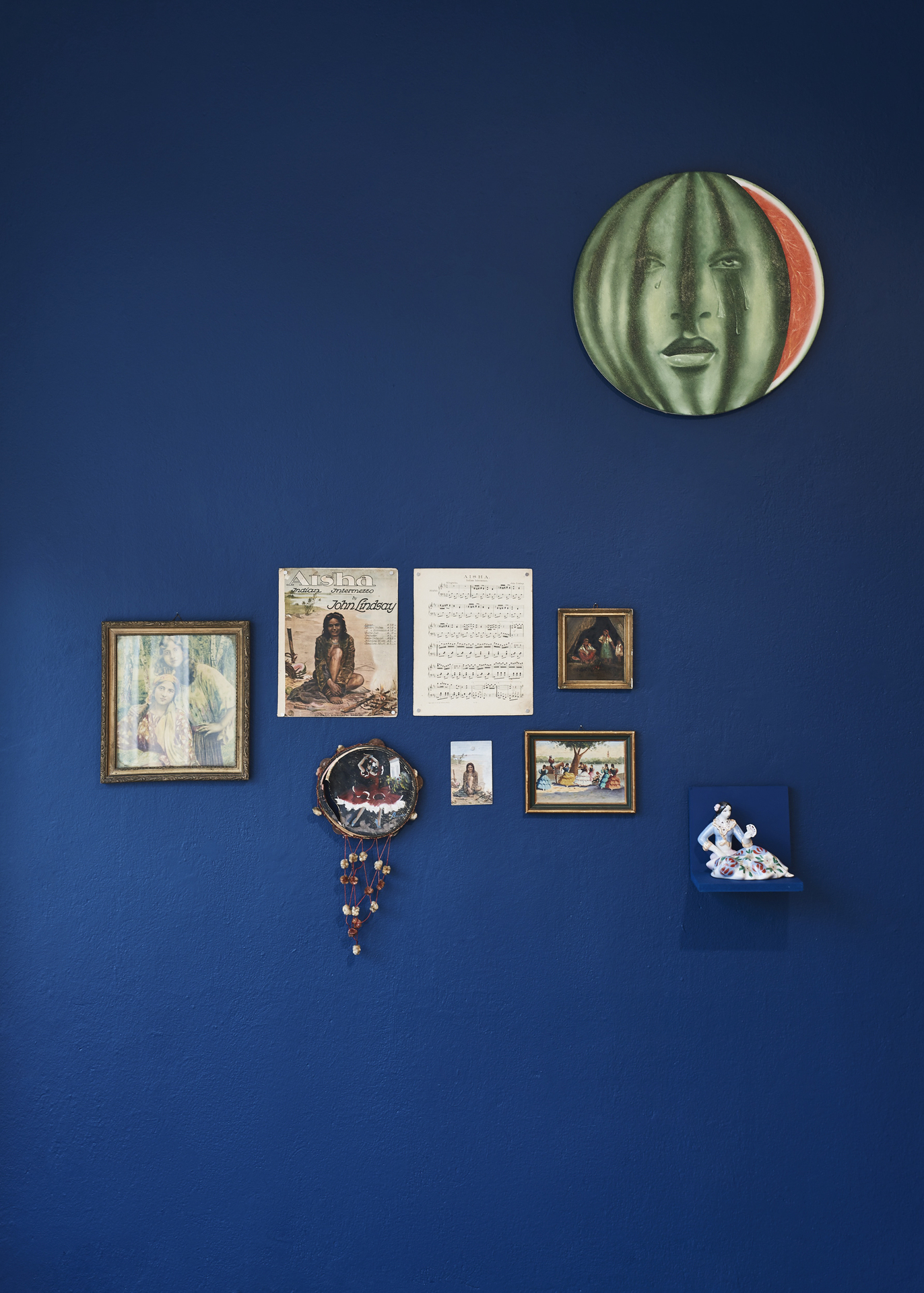

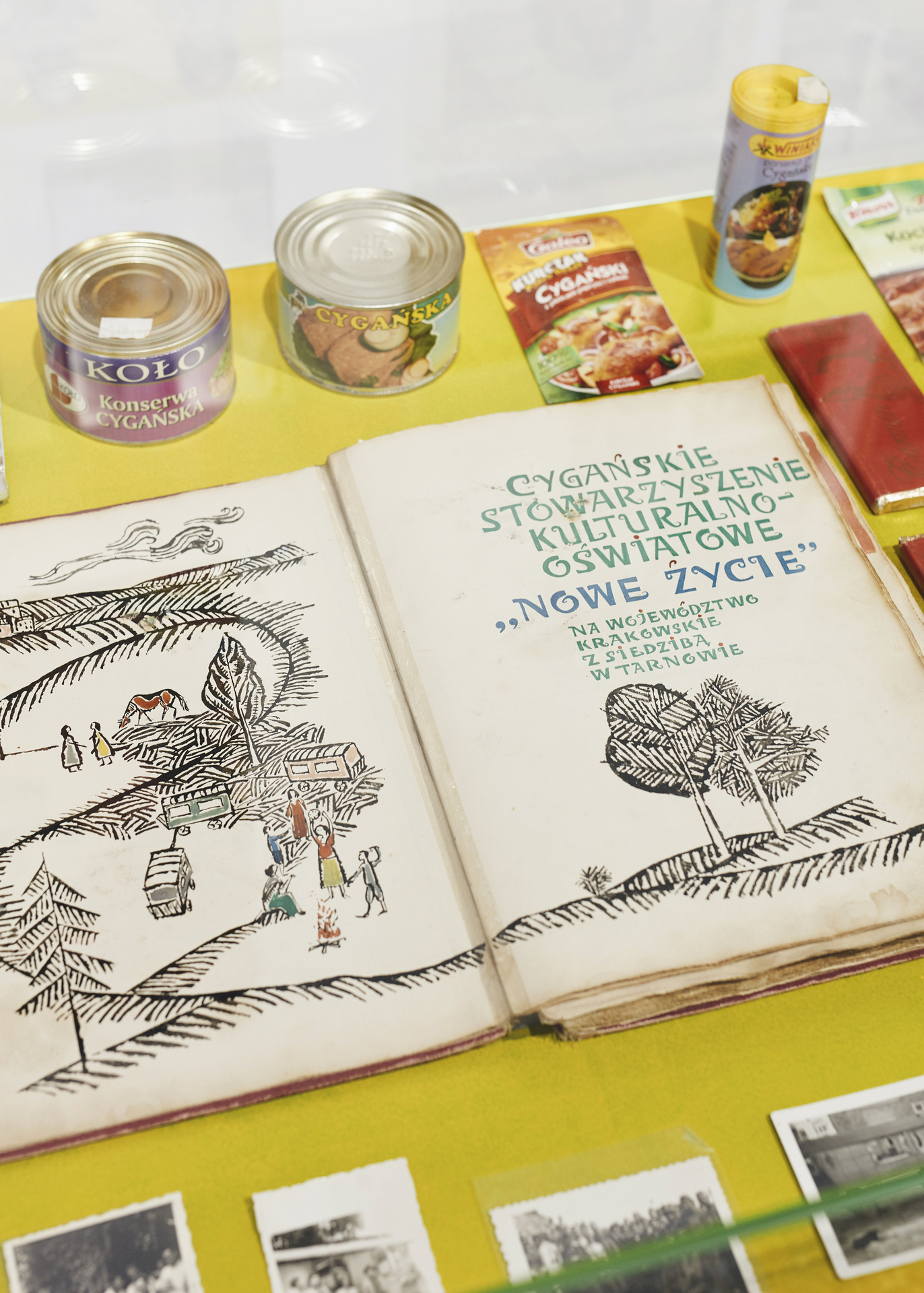

This exhibition is not about the Roma, Romani culture or history. They call me Gypsy but that’s not my name is a story of a “Gypsy”, an imaginary and make-believe figure that has never existed. A story of a construct with its peculiar iconography, of the mythical Orient, Bohemian appropriation and the dialectics of cultural colonialism derived from hybrid mythology and PolishRomani identity. Rather than building a narrative outside the affirmative and narrow imagery, we construct the story from within, disrupting its phantasms and dreamed up revolutions. Yet the meaning of a narrative is not to be found in its core: it surrounds the story like a fruit surrounding the stone. Therefore, in addition to old art, archival pieces, photographs, documentaries, books and recordings – a plethora of creations bordering on political pornography – we are going to show works of modern artists.

***

“It is evident that they have learned nothing from us and admired none of our exploits. Have they been blind and insensitive to our achievements for the last six hundred years or so? One can hardly believe that our world might be so uninteresting.” (Andrzej Stasiuk)

The poet and songwriter Agnieszka Osiecka wrote that the real Gypsies are gone. Perhaps they have never been here. Or perhaps they were here tomorrow, as the Polish word for “tomorrow” is jutro, and that means “yesterday” in Romani. Yesterday equals tomorrow.

Zagraj mi piękny Cyganie (Play for me, my handsome Gypsy) is the title of the compact cassette issued by the pop band Szarotka at the dawn of Poland’s political transformation in the late 1980s. The cover showed a hauntological portrait of an elephant man. Earlier, writer Jerzy Ficowski wrote about Gypsies as he discovered the Romani poet Papusza (although rumour has it that he was the author of her poems while she, the embodiment of whimsical inspiration, was his muse). Wilhelm August Stryowski painted Gypsy men lounging on the beach among ruins of the ancient culture, while Henryk Siemiradzki asked his models to soot their pale faces and wear colourful dresses (not much different from dresses worn by average nineteen-century bourgeoises) to pass for Gypsies. The flashy clothes of Gypsies adorned with glass beads and field flowers and evoking a futuristic vision were described by the 19th century novelist Józef Ignacy Kraszewski in Chata za wsią (The Cottage outside the Village), a novel tackling the problem of Gypsy community discrimination. Equally fanciful were the dresses worn by Duchess Izabela Czartoryska who inspired and played the part of Gypsy Javnuta in the comic opera Cyganie (Gypsies) written by Franciszek Dionizy Kniaźnin. A century later, Kniaźnin’s libretto caught interest of the composer Stanisław Moniuszko. While Kniaźnin focused on assimilation of the defiant Gypsies, Moniuszko was attracted to the romantic idea of their unfettered spirit. “My dear Stach, why aren’t you a Gypsy?”, says Javnuta’s foster daughter to her lover. Exclusion and affirmation are two sides of the same coin.

Gypsies play the part of con men who can tell fortune from coffee grounds and wrung hands, demons casting their evil eye, or singers. Usually, they just sing cheesy disco polo. Herbalists, horse whisperers and bear charmers, they are the sheer embodiment of the Orient, the first true Bohemians, nomads and vagrants living in a suspiciously utopian union with nature. Gypsies are the prototypes of migrants and artists. Or tourists, as referred to by a Gdańsk politician who called for eviction of the Roma from the city’s squats. Gypsies are the neighbours who light fires in their homes and play the accordion under other people’s balconies. Their skin is always too dark and they are always too dirty and too colourful, to quote the poet Adam Mickiewicz. Even the 2013 film Papusza was shot in black-and-white as if to avoid ethno-kitsch reconstruction.

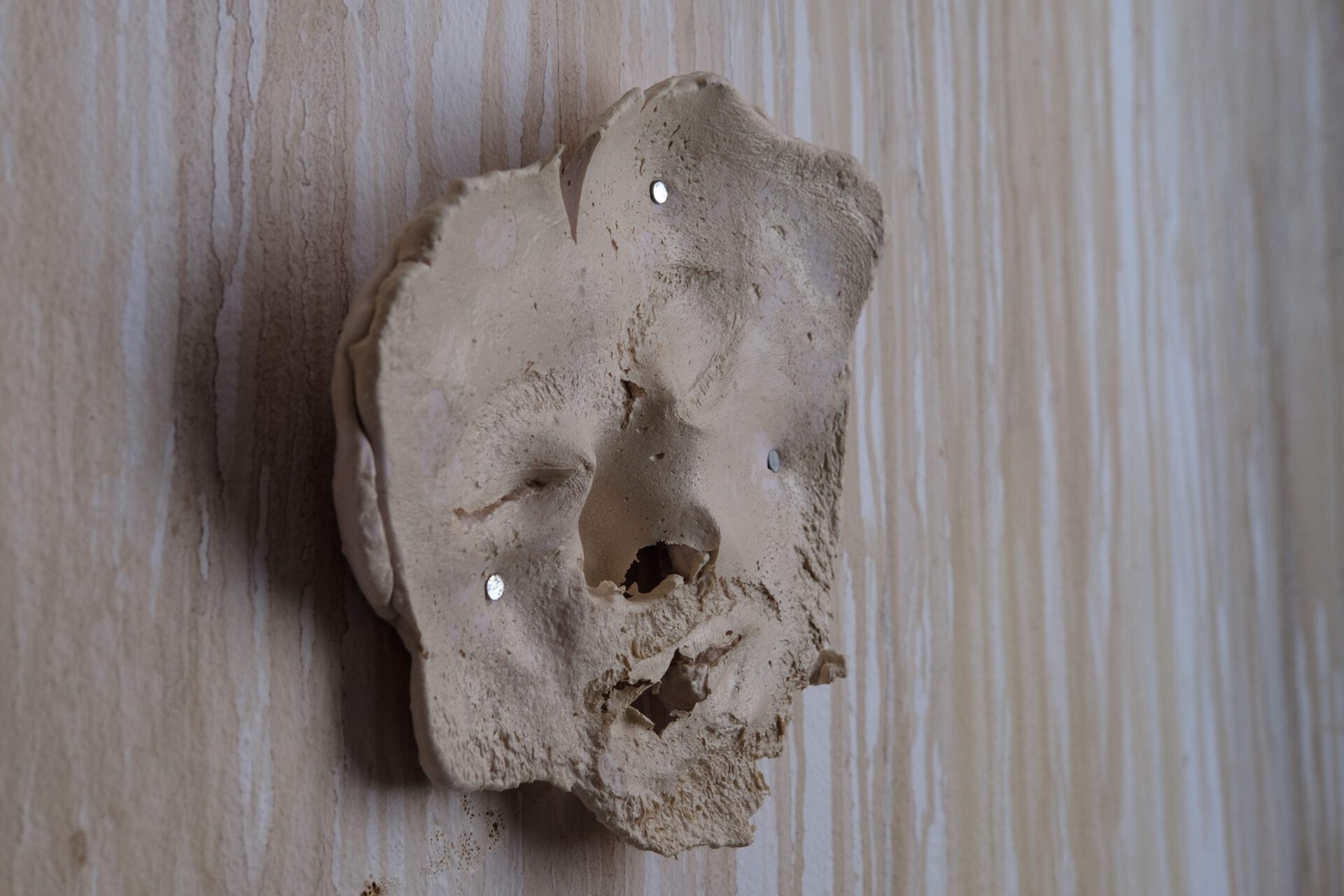

We explore stories of Gypsies told from a non-Gypsy perspective, often unconsciously clichéd, as well as stories where a Gypsy plays the role of a non-Gypsy. We are fascinated by folk masks of traditional carol singers, where alongside the stock figures of the Devil, Stork and Goat comes a grotesque hominid with a straw bear on a rope – the same bear that appears in the communist era comedy Miś (Teddy Bear) responding to the urgent needs of the Polish society. We recollect the story of Prince Karol Radziwiłł “Panie Kochanku”, a patriot and Sarmatian, who brought Gypsies to the multicultural town of Mir, had bears trained to pull carts and allowed the Gypsies to gather for rallies in the fields of the Horeszkowski Castle (the very castle that was immortalised in Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz). The exotic elections of the Gypsy king in Warsaw’s sports stadium in 1937, as reported by the Tygodnik Dźwiękowy weekly. The painting by Antoni Królikiewicz showing a Gypsy woman with a watermelon, which was later printed in foreign newspapers as a portrait of an Indian girl. Writer Witold Gombrowicz, who wanted to be an artist and a Bohemian, and a nobleman among Bohemians. The Gypsy Bible dreamed up by Julian Tuwim, and the story of the 19th artistic group Warsaw Bohemia whose members used to pour soil onto the floors of bourgeois drawing rooms. The Gypsy man with a self-playing violin from Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz’s Nadobnisie i koczkodany (Lovelies and Dowdies), who cried and sobbed while performing for the keenly listening Death. The year 1968, when the Roma, like the Jews, were expelled from Poland, except that the Roma had no Israel to go to and were leaving Poland without passports or identification.

“The gypsies are a theme. And nothing more. I could just as well be a poet of sewing needles or hydraulic landscapes. Besides, this gypsyism gives me the appearance of an uncultured, ignorant and primitive poet that you know very well I’m not”, complained the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca in a letter to his friend.

We are drawn to this aura. We want to immerse ourselves in this sticky and tricky Bohemian atmosphere colonised by live cultures. The cultural construct and folk amalgam. Like there is no tomorrow. Perhaps in the times of resurgent nationalism and deepening migrant and environmental crises there really is no tomorrow. In the 1960s, Günter Grass wanted to bring Romani camps to Berlin: he believed that this would have solved the Berlin Wall question. Because where there are Gypsies, the borders become leaky.

Wołają na mnie Cygan choć tak się nie nazywam

Bo komu to przeszkadza, gdy imię się nie zgadza*

[They call me Gypsy but that’s not my name,

The name doesn’t match and no one’s to blame.]

*Kayah & Bregovič, Caje Sukarije, 1999

Anna Batko