Out of Space: Düsseldorf Variation. An interview with Junni Chen and Sophia Scherer, Curatorial Research residents at the Julia Stoschek Collection

Project Info

- 💙 Julia Stoschek Collection

- 💜 Nelly Gawellek

Share on

NG Hello Junni and Sophia, we’re here to talk about your exhibition Out of Space: Düsseldorf Variation for the Julia Stoschek Collection, but first of all, I would like to learn more about your personal background: Where are you from? What do you deal with in your work?

JC I currently live in New York, but grew up in Singapore. These are two diverse, metropolitan cities where different communities and interests meet, conflate, and clash with each other. My experiences there have made me sensitive to how power operates through the ways in which our cities are designed and planned. The spatio-architectural strategies implemented by both state and non-state actors can, intentionally or unintentionally, produce the invisibility of marginalized communities. The ubiquitous shopping mall which proliferates throughout Singapore is one such site in which we can investigate how the design of space itself constructs a social system that makes only a certain population – those who can take part in economic exchange – welcome. In short, questions of visibility, representation, and power, explored through how interfaces, buildings, and spaces are designed, interest me and many of my frequent collaborators.

SoS I live between Berlin and Frankfurt, where I am about to finish my Master in Curatorial Studies at Städelschule/Goethe University. My background is in art history and arts and cultural management, which I studied in Berlin, Osaka and Karlsruhe and I work as a curator, doing mostly freelance projects. I am interested in artistic and curatorial approaches, which seek for a reference to the public or notions of publicness – spatially and critically, such as rethinking collection strategies, or practices that deal with the question around intersections of art and life, which first came up in the 1960s but are still relevant today. In this spirit, video is a groundbreaking medium, combining multiple artistic fields, constantly looking for different modes of spectatorship and reaching beyond the material dynamics of space.

NG You are the fellows of the Curatorial Research Residency Program at the Julia Stoschek Collection 2021/22. How did you approach the extensive collection? Did you have specific questions in mind?

JC I didn’t have a specific idea or approach for researching the collection, in part because it is such a wide-ranging collection. What I enjoyed particularly was the freedom to meander within the JSC Video Lounge and watch works by artists that I respected and followed, but never had the chance to see before. Some of the first works that I watched during my residency period were Sophia Al-Maria’s Beast Type Song (2019), Klara Líden’s Grounding (2018), and Eleanor Antin’s The King (1972). To be able to view pioneering works from the 1970s, up until the digital works of today, in such a free and unfettered way was a privilege.

SoS The variety of video works in the collection was quite overwhelming for me at first. So, I focussed on my interest in aspects of spatial perception, for example the meaning of “sites/non-sites” embraced by Robert Smithson’s work Spiral Jetty (1970), or how video deals with architectural spaces or landmarks, with a distinct focus on social interactions. The works by Cyprien Gaillard have always inspired me to look at the surrounding world, its inscribed histories, materialities and present condition from another perspective. This led me to Oliver Payne & Nick Relph’s video work Gentlemen (2003), an anti-documentary, that through an eclectic and blurry imagery creates an alternative way of appropriating and viewing public spaces. The artist duo speaks from the perspective of an alienated youth culture, but instead of a rebellious protest against the establishment, politics of globalization or dominating neo-capitalism, they create a colorful and poetic, dysfunctional and non-narrative film which explores public space in an almost derivé-like manner, emitted by the Situationist movement. By doing that, they embrace and exaggerate what is seen as rather unattractive in the urban space. This was somehow a point of departure for me to look deeper into filmic strategies concentrating on the conditions of shared, public spaces and challenge normative attitudes towards the everyday, and towards authorities.

NG When did you decide to work together on an exhibition?

JC We both met in Berlin in the summer of 2021, also as part of our fellowships. At that time Sophia was already working on an exhibition about the tension between private and public spaces, and I was in the midst of developing my graduate exhibition at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, which addressed issues related to the breakneck pace of redevelopment in dense urban cities. We had common research interests, and when the JSC asked if we would like to curate a project together, we both said yes. As we believe curatorial collaborations create a wider concept and network of thoughts, we were happy to combine our research approaches.

NG What did your residency look like? And in terms of your exhibition theme: Was it more of a collection research or a city walk?

SoS For me it was definitely based on collection research, but when you’re new to a city, walks are mandatory at some point to get an understanding of the social fabric of a city. I was always impressed by the unmistakable mix of modernist architecture, and futuristic building styles that exist in Düsseldorf. It’s a city that has embraced spatial changes over the last decades.

JC Agreed. I would also say that my residency was rooted a lot in exploration of the region, of Germany in general, and broader Europe, and my foray into the collection’s works bled into my own lived experiences as well.

NG In your project Out of Space: Düsseldorf Variation, you take over 20 works from the collection and bring them to different locations in Düsseldorf. How did you come up with the idea for the exhibition?

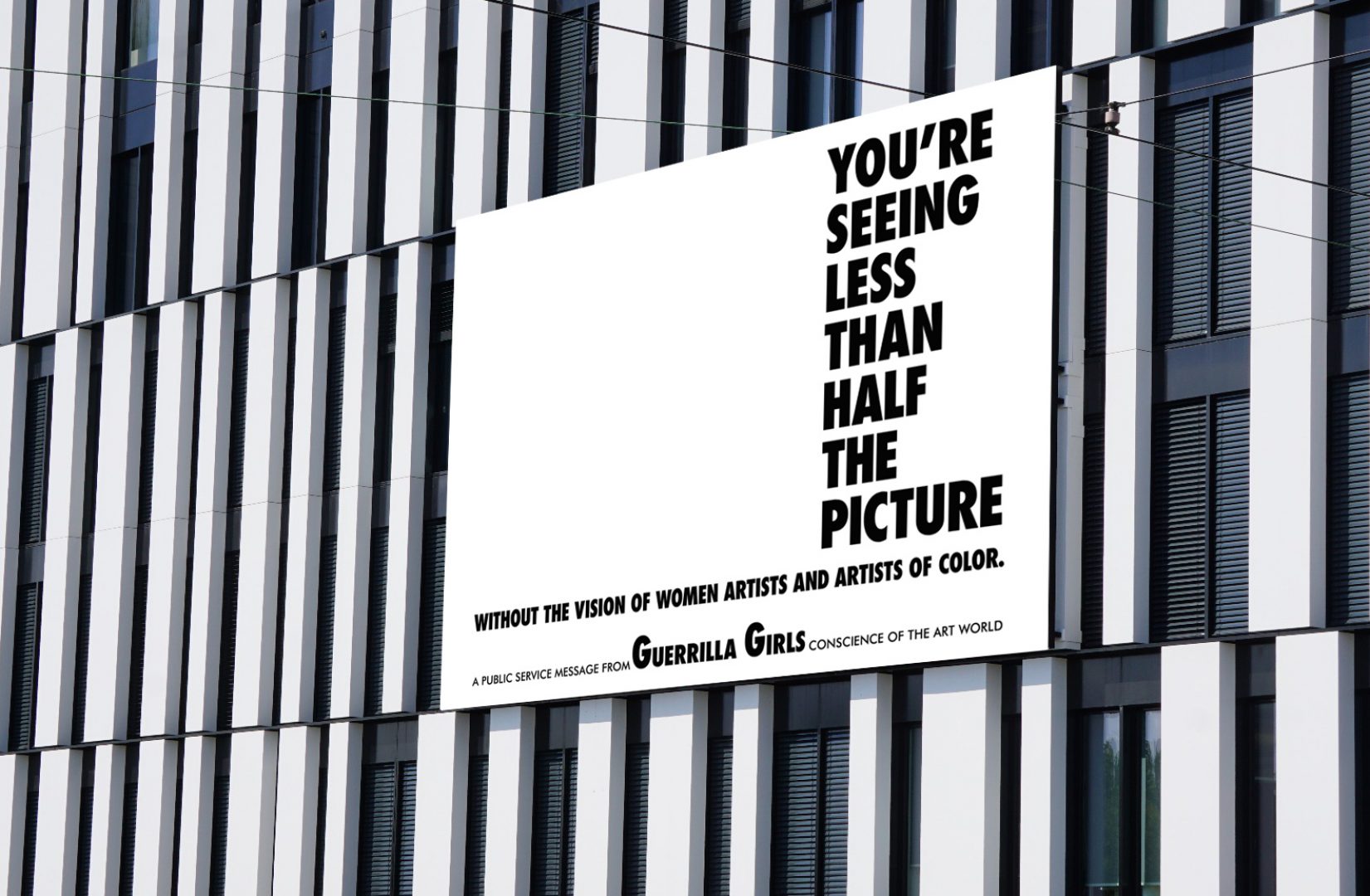

JC Since the collection was celebrating 15 years of exhibitions in the JSC building, we thought it was a good opportunity to reach more people beyond the foundation’s walls. Although there is the JSC Video Lounge, which is available online, we were thinking about reaching an audience that may not have encountered these video works before. A part of our intention with making this exhibition was to encourage unexpected encounters. You could be driving down the road on your way to work and see the large Guerrilla Girls poster on the façade of the landmark building La Tête, or walking down the Kö (the main shopping street in Düsseldorf) and see Nora Turato’s new poster series, thirst never stops (2022). These provocative works can evoke unsettled feelings – of curiosity, wonder, or irritation. Even if they are fleeting encounters, we hope that these works can offer reflections on the environments that they are displayed in.

NG How did you come up with the locations and architectures and what role do the respective architectures and locations play?

JC We arrived at the locations through various routes: the staff at JSC helped immensely with brainstorming about locations, and building collaborative partnerships. There were also some locations that Sophia and I knew we wanted to approach. The Bilker Bunker, for example, was one such space. Historically, it was used as an air raid bunker, but today it is being repurposed as an experimental arts space. Highlighting venues like that was important for us as they helped us engage the socio-historical legacies that our cities grew out of and are also intimately intertwined with. In most cases, the venues function as a backdrop to the works themselves. To take the example of the Bilker Bunker again, we are presenting works by Ana Mendieta and Anne Imhof which are very emotionally charged. In a way, the historical context that the Bilker Bunker provides reinforces an awareness of how our collective memories still undergird our cities on an affective level. In other places, such as the Ando Future Studios – a kind of counterpoint to the Bilker Bunker, since it is a new real estate development – we chose to show 2 Lizards (2020), by filmmakers Orian Barki and Meriem Bennani. The work, which originally debuted as 8 short Instagram videos, explore the lives of two animated lizards living in New York during the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s a poignant, and yet humorous work that considers the anxieties, discomforts, and struggles of living within a city in crisis. In a way, it complicates the future-forward optimism engendered by the tone of such neo-capitalist real estate projects.

SoS Moreover, nowadays we expect to see video works in an environment intended for their presentation. From the genealogical point of view, media art has always appropriated other places for its presentation, starting with Expanded Cinema, or early video works shown in Gerry Schum’s gallery on TV, or experimental projections in public by Dan Graham. Tracing this media-specific dynamic is incredibly exciting, also in terms of creating a counter-position to digitally consumed media and re-focussing on viewing art collectively at sites that create a recontextualization of the respective works shown.

NG In addition to the reoccupation of urban space as a place for collective experience - what issues will visitors and passers-by encounter?

SoS Some of the exhibited video works, such as those by Hannah Black, Dara Friedman, Klara Lidén, Oliver Payne & Nick Relph, Cao Fei, and the Guerrilla Girls, explicitly make public space the setting of their cinematic and partly performative artistic explorations. In these works, the visibility of certain groups of people, their inclusion or exclusion from urban life are negotiated. These works show normative forms of behavior that underlie social and often contested spaces of action, and how they can be disrupted. Power dynamics inscribed in certain places are revealed by means of artistic interventions, with subversive, sometimes humorous or grotesque narratives. Other works, such as those by Ana Mendieta, Anne Imhof, Beatrice Gibson, and Kandis Williams, recontextualize themselves through their presentation in respective locations. Attention is focused on perceptions of shelter, spatial boundaries, and especially the transition from the private to the political. Subjective urges for visibility and acknowledgement juxtaposed against the backdrop of reality. Potentials of self-empowerment, renewal, and collective reappraisal are explored therein.

NG Maybe this can only be said after the exhibition, but I still ask: What happens to artistic works in such a context? Or the other way around: what happens to these places when they are transformed in this way?

SoS At the Dreischeibenhaus for example, we find two video works installed in the lobby area. Usually office workers wait here for their appointments and then disappear to the upper floors. The atmosphere in the lobby reveals a tension between private, corporate and public interests, a moment of transition and passage. The works by James Richards and Beatrice Gibson reveal an intimate negotiation of emotions, sensation and sensory perception. They disrupt or irritate the clean environment, at least for a moment. I think these moments of irritation were tempting from the outset of this project. Whereas the work of Kandis Williams perfectly blends in the environment, which almost seems to be a site of the performances documented in the video. So, each of the works has an individual link or dialogue with its setting.

NG Is there a starting and ending point for the exhibition? What experiences do you hope visitors will have?

JC There is no prescribed starting and ending point for the exhibition. That being said, most of the exhibition’s works are concentrated within the “Stadtmitte” and “Altstadt” areas. Visitors might be able to plan their own walking tour using a map that we developed for the exhibition. It’s recommended to invest some time to see at least a few places and also take the chance to go there at night. The exhibition encompasses such a wide range of location types, in part because we wanted visitors to become attuned to the differences in experiencing a semi-public, and a fully public space. There are relative degrees of publicness for each location, each designed in accordance with ideals of how accessible a location should be made. The Dreischeibenhaus, for example, is a location that usually is closed to the general public, and the visitor’s experience of navigating and behaving in that space is different from, say, going to Buchhandlung Walther König, or the Salon des Amateurs. It gets us to think more deeply about what kinds of design or management strategies are at work within these spaces, and how we take them as natural, or for granted.

NG The discourse around public space, especially urban space, is very much about economies: Living space, usability, visibility or attention are essential factors. I imagine that this might lead to conflicts in your own practice, showing art within a contested territory?

SoS Of course, it’s not our concern to help the collaborators enforce their interests, but we’re aware it might be an effect. However, our idea is to lay a new focus on locations, that are either there for a long time, but not accessible, or are not seen as promoting the art scene. On the contrary, many of the artworks themselves subversively challenge the ideologies of these places, some through humorous, grotesque ways or in a very touching and serious sense. I think it’s interesting to enter into a cooperation where main interests are far apart (or maybe not so much). Frictions can and should appear, otherwise we could all stay within our comfort zones and forget about the idea of exchanging and confronting deviating world views. Nevertheless, the risks and benefits of gentrification through art and exhibitions is such a controversial topic, that would fill another conversation.

JC We thought about the dynamics of our selected locations during our time developing the exhibition. For venues like Buchhandlung Walther König and the Salon des Amateurs, our collaboration felt very natural, because they are already part of the artistic community in Düsseldorf, and the broader NRW region including Cologne. We also chose to collaborate with places such as Hotel Nikko and Dreischeibenhaus because they are just such unexpected places for the presentation of visual art, which hopefully helps us reach a broader audience. However, we also want to complicate the idea that our cities are completely at the mercy of big corporate or statist interests. Cities are dynamic; our cityscapes are always in flux, constantly being re-made through dynamic exchange, ebb, and flow. Even if private or state interests attempt to impose order through urban or architectural planning, there is always the potential for organic or spontaneous acts that challenge and subvert efforts to manage – or even more drastically police – our public spaces. I think a lot about the civil rights movements that have sprung up in cities all over the world, and how protestors have self-organized to protest police brutality, racism, and the suppression of minorities. It gives hope that our cities are constantly in flux, and that we can continue to counter over-privatization, enclosure, and territorialization of our urban spaces.

Out of Space: Düsseldorf Variation, curated by Junni Chen and Sophia Scherer is on view from 31 August – 4 September 2022

More KUBAPARIS