Susurros Barrocos – Barockes Flüstern

Project Info

- 🖤 Mercedes Azpilicueta

- 💙 Sammlung Philara

- 💜 Nelly Gawellek

Share on

An interview with Mercedes Azpilicueta about her current exhibition at Sammlung Philara

NG Before we start to talk about your current exhibition at Philara, maybe you could tell me a little bit about your artistic background. Where do you come from? What topics are you interested in?

MA I was born and raised in Argentina where I spent a big part of my adult life. I already studied art in Buenos Aires and at that time, I was juggling several jobs here and there: I worked as a gallery assistant, I gave Spanish classes, and taught Aesthetics at the Art Academy. Back then, I was mostly connected to the literary scene, and spent a lot of time with poetry publishers and writers. It was a mix of scenes and disciplines. And then I received a scholarship to study at the Dutch Art Institute, which was my first time travelling to Europe. When I came to Europe, I thought "Oh, so much space for culture, so many artists, so many resources!" Everything seemed fantastic and accessible and easy at a first glance. Of course, there are constraints here, too, especially when it comes to gender-based discrimination. Already from the early years in Amsterdam my practice became much more performative, even though on a personal level it was still very much affected by how things would function back in Argentina. Most of the topics I deal with in my artistic work come from my lived experience. They are part of my life, part of who I am and what I have been through.It's important for me not to land on a topic like with a helicopter... I engage with something from a situated perspective.

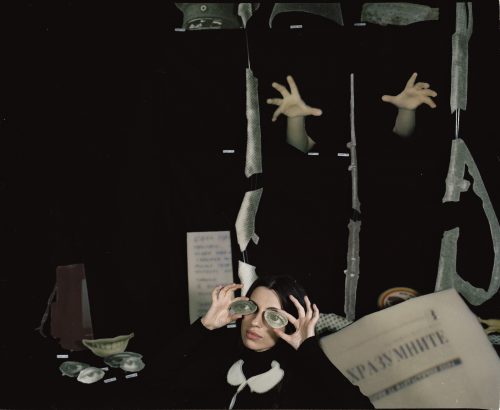

NG The first work we see, when we enter the exhibition space at the Philara Collection is a huge, delicate jacquard tapestry, unfolding from a scaffold, Potatoes, Riots and Other Imaginaries, (2021). The tapestry is a picture collage and a sculpture at the same time and it is combined with white objects that have a self-made look, like a crochet vest, or a macramé flower basket. Through a speaker we hear the sound of a sewing machine or a march drum, and people talking. How did all of these elements come together and how are they connected?

MA I wanted to create a spatial dramaturgy for the viewer to enter, a situation that activates the body, connected to my love for the performative. The white objects look like costumes or garments, things you could wear. Then there is the voice, which is something that genuinely comes from the body and projects into other bodies. The tapestry functions almost as a backdrop or décor for a setting, which is borrowed from theatre vocabulary. The imagery is taken from various sources: archival images of the so-called "Potato Riots" from 1917, or photos my sister and I took on the streets in Buenos Aires during the marches of NiUnaMenos, a movement which protests against femicides and gender-based violence. It's a mix of personal and public contexts. The work is not a unity, it's opening up, multiplying... In my compositions I juxtapose the real with the unknown: I get inspired by fictional Latino literature; blending reality and fiction where you have a piece of information, a historical fact, but right next to it you have something imagined, something that is not actually true. A little bit like Surrealism, but that's a European term, of course. The tapestry is made by a Jacquard weaving machine while the white garments are handmade, with the use of cheap materials,functioning as counter elements. It's a statement towards accessibility of resources: sometimes you're lucky as an artist to have a big budget for production, but it's also possible to do something with very little.

NG I noticed on your website you mention quite a long list of collaborators for this installation. What do these collaborations mean to you?

MA I am a visual artist, but sometimes I wish I could work in the theatre or be a musician, and I'm flirting with it, borrowing from it. I work with a small group. The sound piece, for example, was made together with Constanza Castagnet, an Argentinian artist, based here in the Netherlands. The people I collaborate with are autonomous makers and artists on their own with whom I share a similar background. It's a little bit like in a theatre company or a film production, where everyone has a specific role and is credited as such. As an artist, I don't know everything myself, and I don't have all the answers [laughs]. In terms of economy, I try to redistribute resources as much as I can. So, if I get a generous budget, I try to share it with my colleagues in Argentina or Chile. Collectivity is something that I practise along the way, especially when you are working on an installation that speaks about labor you have to be consequent.

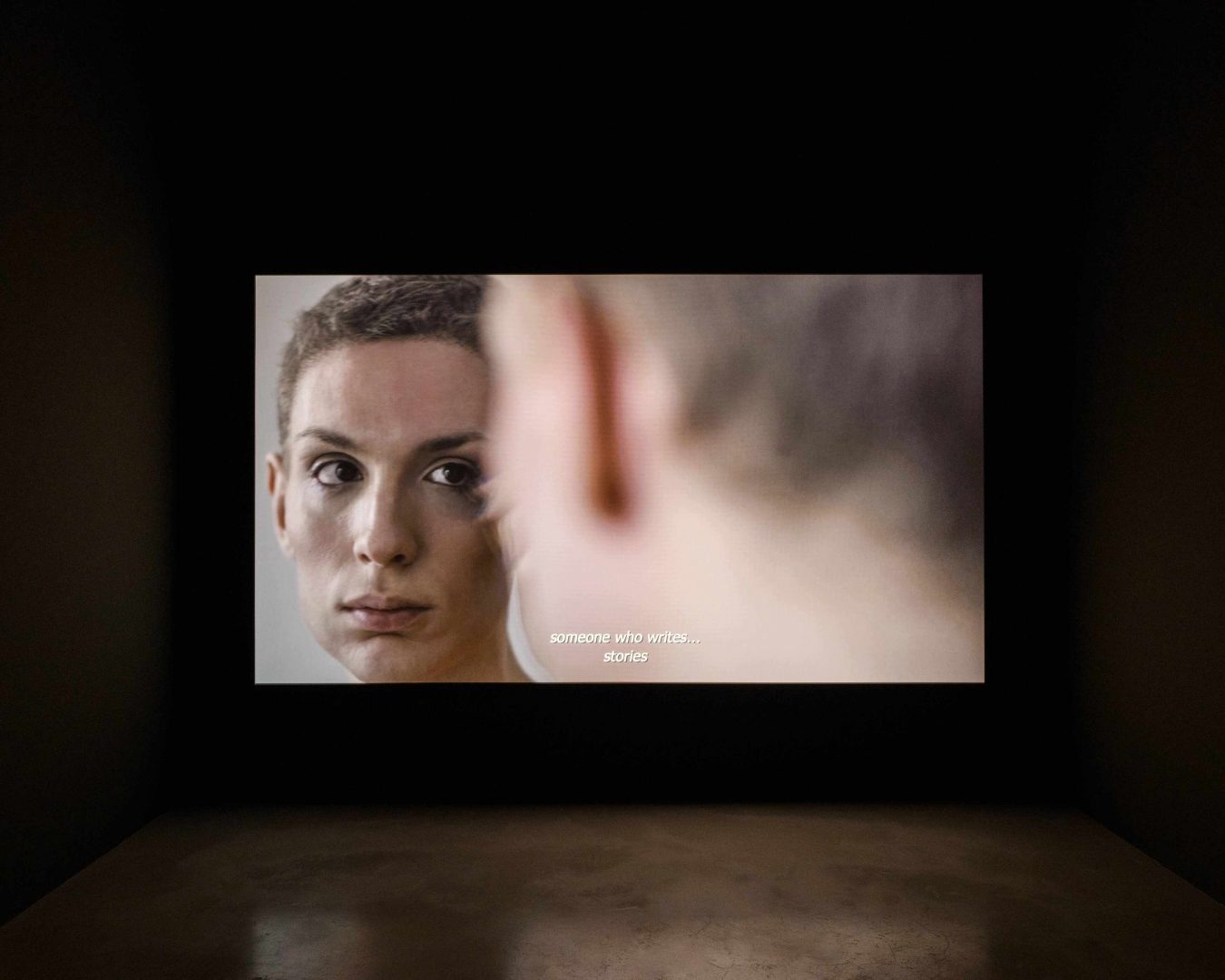

NG Clearly, the medium becomes the message here... In another tapestry you illustrate the story of Catalina de Erauso, a nun from the 17th century, who lived under male identities and served in the military. Why did you choose to tell this story?

MA Literature inspires me, but also characters who write, or travel. In spite of the distance in history and time, I feel connected to them, because they left behind their place of birth, crossed cultures. One of my friends and collaborators from Buenos Aires, Veronica Rossi, is a curator at the Latin American Art Museum and she introduced me to the story of Catalina de Erauso. The first thing that comes to mind from today's perspective is, that she – or he – is this queer character from the past, a lieutenant nun. But maybe Catalina just wanted to travel and the only way she could do it was to switch genders. As a woman back then you could either be a wife and mother, you could be a nun, or you could be a prostitute. There are various interpretations: some scholars in Gender Studies would call her a polyamorous person, because she was having several relationships. But others would say: "Well, we cannot look at her through these contemporary glasses". And then there is the fact that as a lieutenant, he was a terrible conquistador, who was actually told off by the crown because of how cruel he was in battles. When you look into this history, you understand that it cannot be told in only one way, it's not something you can just repeat. By retelling you automatically weave your own perspective into it.

NG Did you know that in German, we say "Stoff" (fabric, matter) as a metaphor for "Geschichte" (story)? I had to think of it, while reading the work titles, which are a mix of Spanish, German, and English translations. As an artist working between cultures and languages these translations seem to be important to you.

MA That's nice! I remember, when we discussed the title of the show, we wanted to refer to the Baroque, because it's an idea I constantly come back to in my projects. The style was brought to Latin America through colonisation, mainly by Spain and Portugal, but it's not the same Baroque as the one in Europe, because it was mixed with local and traditional elements. For example, you have images of the Virgin Mary who has brown skin or is surrounded by jungle animals. We decided to have the title in Spanish and German Susurros Barrocos - Barockes Flüstern. English is the language the world chose at some point. Not having the title translated to English is a kind of a micro militancy against this predominance and the overall idea of communicating. It's about understanding the importance of the Other, understanding how "Barroco" sounds differently in Spanish, than in English, and just the music of it, in a way. It shows the difficulties to produce a proper translation, the difficulties to find a proper, clean understanding of history. Everything is in a constant state of becoming, in a constant realisation with flaws, with mistakes, with these "dirty" translations. For me, it's also a reminder to myself of what the purpose of my work is.

NG All of these histories, they could weigh heavy, but you seem to find a very playful, poetic, sometimes humorous approach to them. I’m thinking for example of the two most recent works here, The Resting Quote and The Tasty Quote (both 2022), where you refer to Fluxus artist Anne Marie Jehle. They seem to mark the beginning and the end of the exhibition.

MA I have a very strong interest in the body and in the idea of the domestic: What's the shape of the place where I live? What's the shape of the bodies that I engage in a conversation with – whether they are alive or dead? Anne Marie Jehle, the women from the Potato Riots, my colleagues and peers... How does this multiplicity of bodies behave? I encountered Anne Marie Jehle at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein and her work reminded me of some artists from Latin America from the 1990s. I saw photos of her house and it’s hard to tell what's an artwork from what's furniture. In Argentina there was a movement, part of the Centro Cultural Rojas, that praised works made with simple materials, like a piece of cardboard, some little beads that you have in a drawer, a cup, or glue. It's very haptic, tactile to the eyes. A bit dirty, and messy in a way that it's difficult to understand what is art and what is part of “real life”,, but when brought to an institution, it's suddenly clear: This is an installation. One thing I really admire in other artists is when they merge their lives with their work. And I try to do that as much as I can, even though the exhibition later looks very different from that initial thought. The works are bodies of their own, they can linger and move around. The chair is a fragment of another installation that happens to be there. It's clearly a chair, easy to read in a way, but it's also a little strange, or surreal, and might be a door to something different.

NG The whole exhibition reminded me of exploring a contemporary cabinet of curiosities, or a diorama, like in a History Museum. It’s a condensate of images, objects, ideas from very different sources, contexts, ages… It also affects our various senses, with sound, movement, gesture… How would you wish your works and this exhibition to be perceived by the viewers?

MA Well, I keep coming back to the body, and I am thinking about my mother or about whoever organises a home: It's like when you open the fridge to prepare dinner. What do you have? Some potatoes from last night. A piece of tortilla, one tomato. Okay. What do we do with it? [laughs] Similarly, I wanted to work with leather, and its kinkyness. So, let's get a leather jacket, and a skirt. And what can we combine? What do we have in the studio? A silk fabric and some copper pieces. Let's use it. In this way, it's a very intuitive process... and then, when brought together, the works have their own presence, the materials bring with them their own stories, their tactility, which then affects the viewer's bodies. And that, again, goes back to moving, migrating, leaving things behind, approaching a new territory, a new culture, a new language. New histories even.

NG I suppose we could go on and on and there are more topics we haven't even touched, yet, but let's leave a little for the viewer's to explore. Thank you, Mercedes, it was a pleasure.

MA Yes, I agree. Thank you, too.

The conversation took place over Zoom and was edited by Nelly Gawellek and Angeliki Tzortzakaki for publication.

More KUBAPARIS