Anastasia Komar

Hosts

Project Info

- 💙 Fragment Gallery

- 🖤 Anastasia Komar

- 💜 Justin Kamp

- 💛 all images courtesy of artists and Fragment

Share on

Advertisement

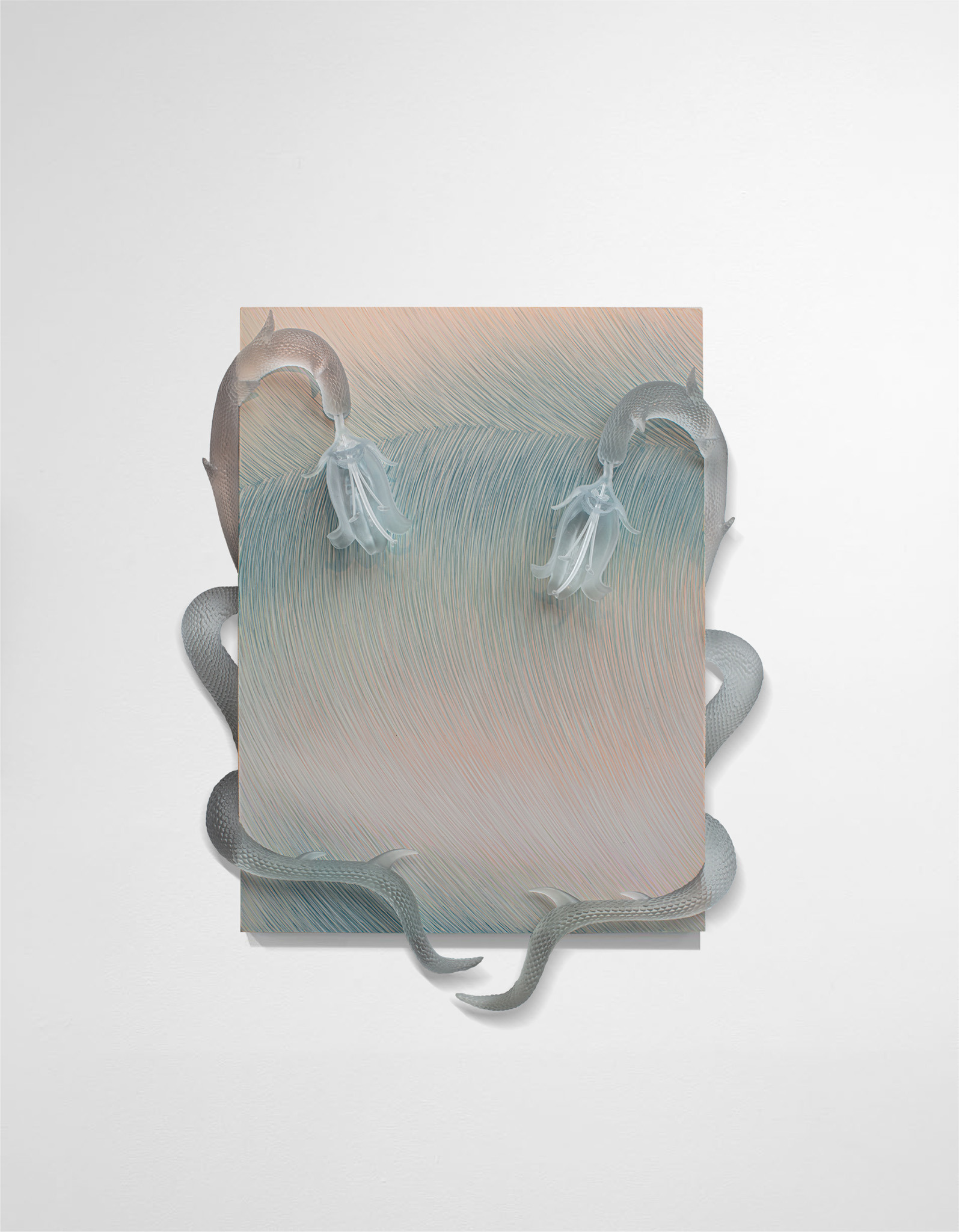

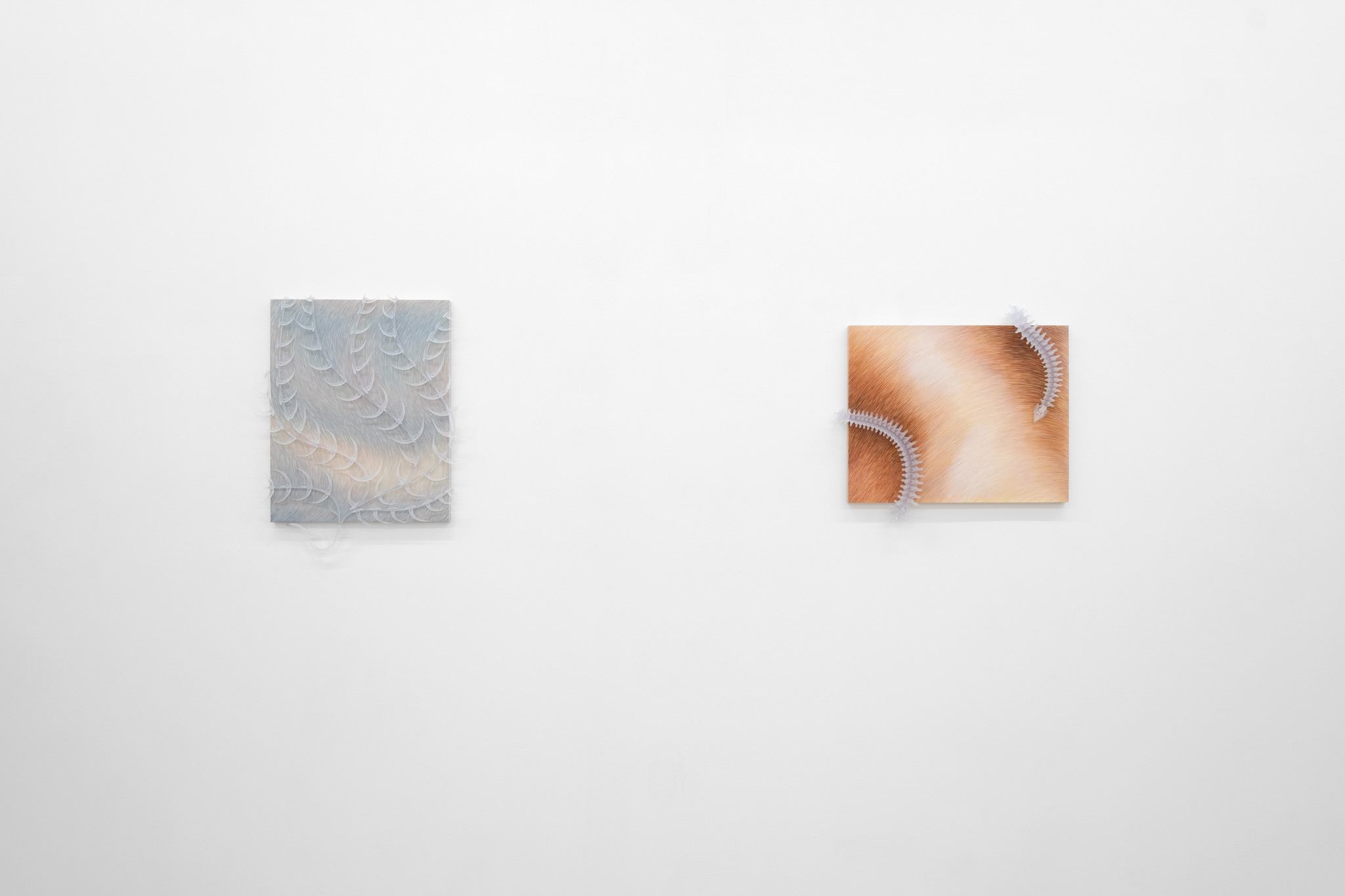

A frosted vine stretches across a dappled indigo field. It worms out from behind the canvas, inching across the picture plane. The vine is sprouting flowers, ghostlike blooms that crane off the canvas and out into the open air. The work is a texture gone dilapidated, now overgrown with phantoms. It’s called “Astrocyte,” Anastasia explains to me, named for a star-shaped cell that controls “perception, imagination, creativity, and conception of ideas”. Outside the studio windows are cranes, high-rises, the low hum of a weekday afternoon in the financial district. Another flowering piece hangs nearby, this one named Samsara: rebirth, the wheel of Vedic tradition. “DNA holds the master design of our spiritual, mental, and emotional states,” she says about the piece. “Our cells are capable of recalling memories and experiences given the right stimulus.” Reincarnation is not a process of the soul, she is saying, but a thing that happens at a cellular level.

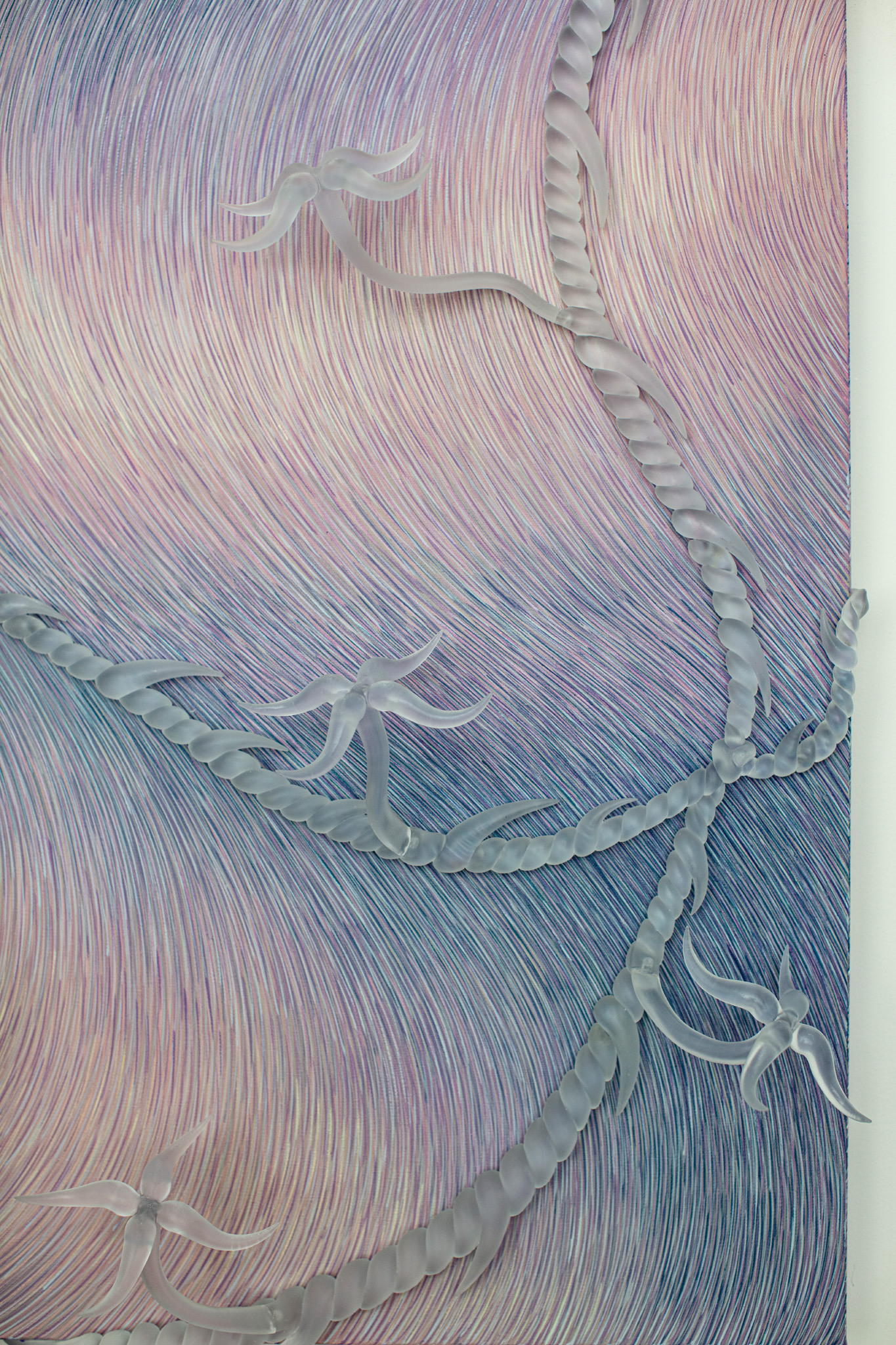

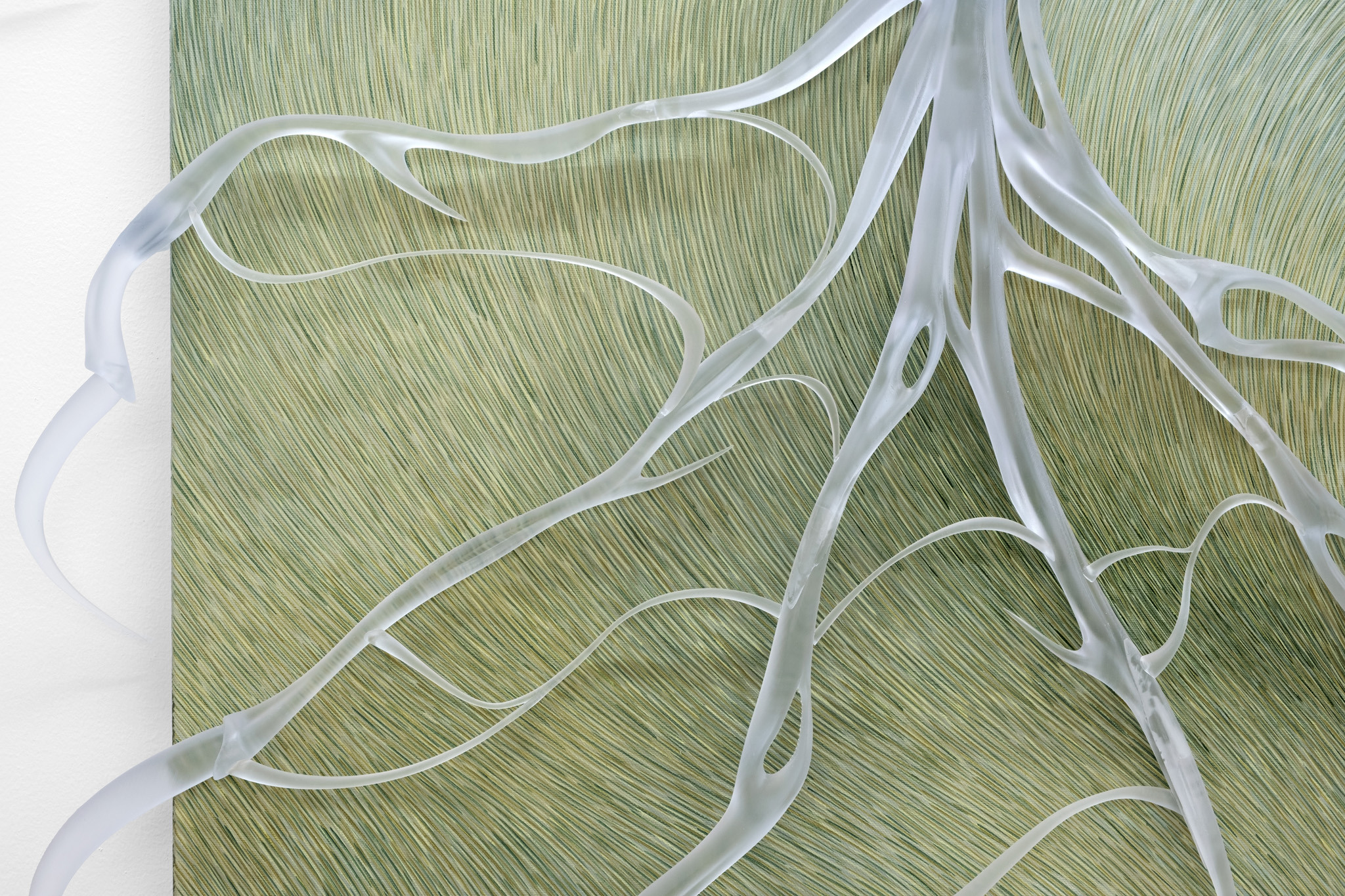

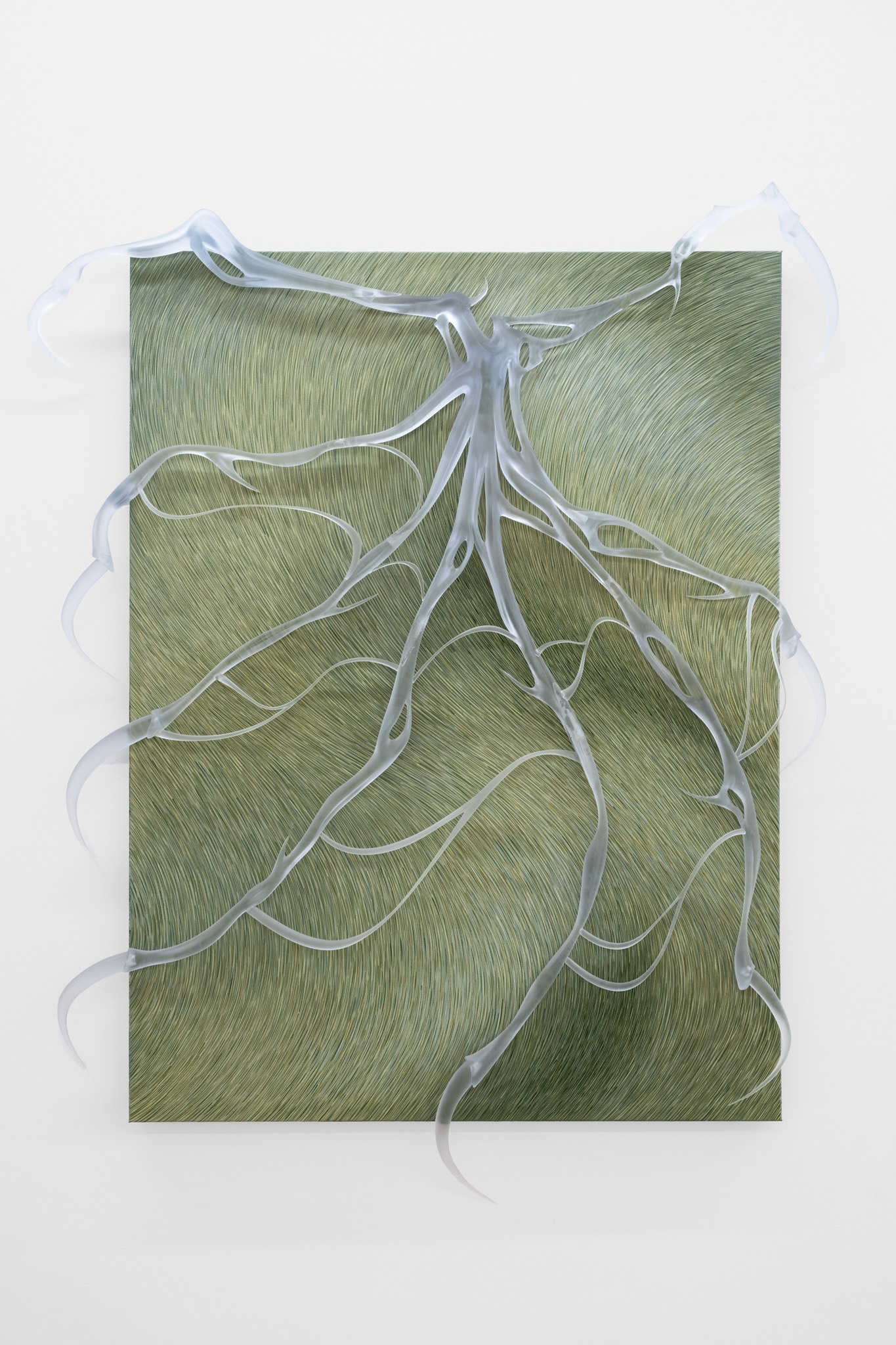

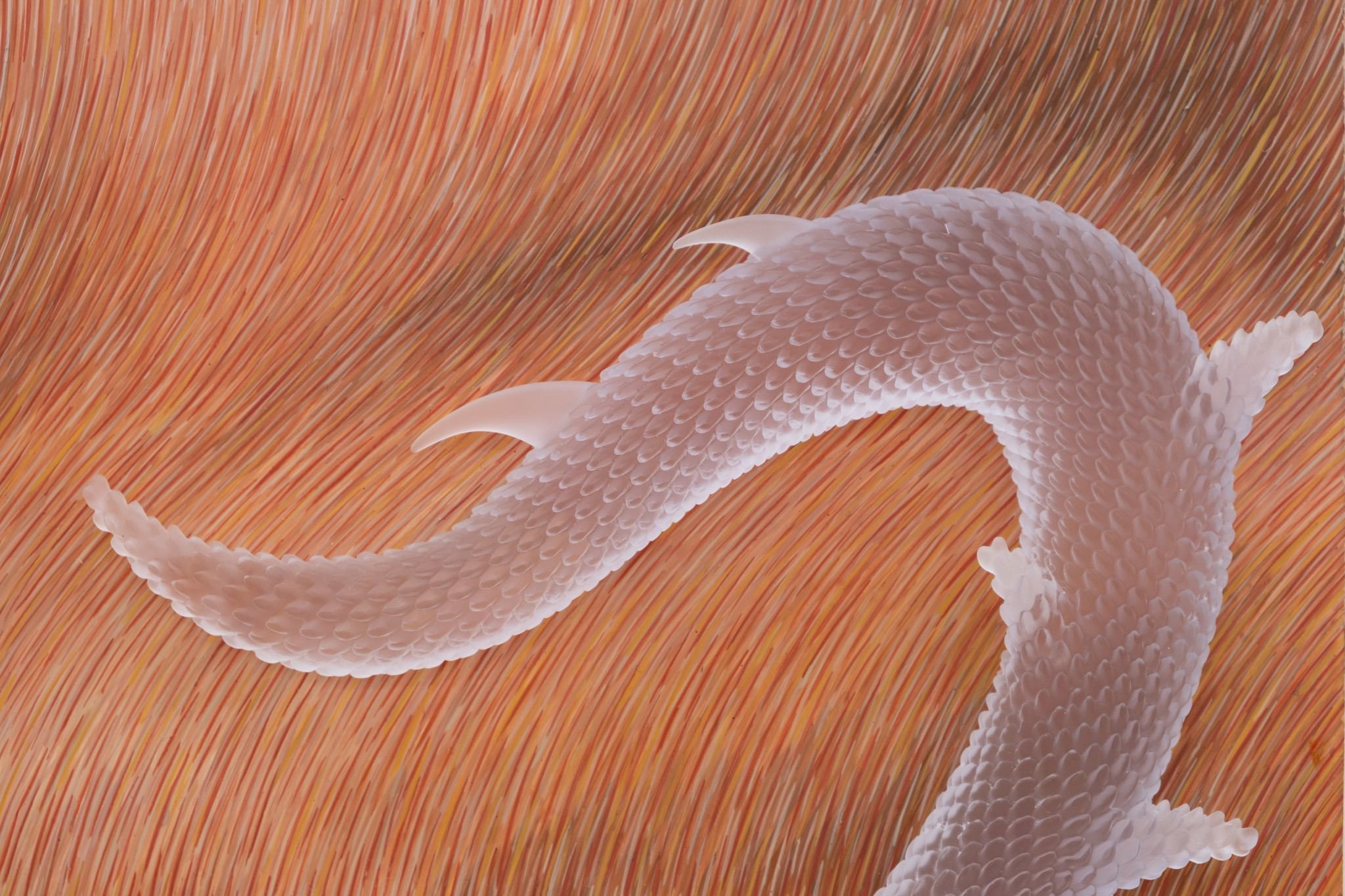

In Anastasia’s practice, the empirical and the spiritual overlap and intertwine. There is biology in the ghost-tendriled works that make up Hosts, seen in the orchid-like pendula of Samsara and Astrocyte or the serpentine elements of Ouroboros, but that biology is braided with a belief in ineffable planes of creation: those diaphanous fields of tonal hatch marks that dance across her canvases, which Anastasia describes as representations of the invisible substrate of the natural world. Not cells, and not the karmic circle of reincarnation, but close-cropped views of some still as-of-yet undiscovered plane that organizes the world - an Aether.

But discovery is coming, she believes. “Trust the science,” goes the refrain, here meaning a faith that this aether will be revealed with enough devoted study. She began this body of work during the pandemic when the nominally unseen routes of aerosol transmission and supply chain fulfillment suddenly became alarmingly visible. In her studio she has hung pictures of irradiated daisies, root structures, the growth stages of ferns; as I walk among her workspace she tells me she’s been reading the work of Soviet Cosmists like Alexander Chizhevsky, who believed that revolutionary movements could be mapped to 11-year cycles of solar activity, with social fervor peaking alongside the sun’s heightened output. So much depends on the belief that there is an order to things, that the universe is not blindly falling but rests instead on some inherent structure, drawn and maintained by natural laws or otherwise: solar unrest, cellular memory, the cycle of Samsara.

So it is with the visual arts, too: in her essay “The Originality of the Avant-Garde,” Rosalind Krauss attempted to map the guiding pictorial principle of modernism, focusing on the omnipresent grids of Malevich, Mondrian, and beyond. In the silent, centerless grid, Krauss wrote, the modernists thought they had found a new original myth of Art, one without the hierarchy inherent in perspectival geometry. Their embrace of the grid was the product of “peeling back layer after layer of representation” until they arrived finally at what they saw as the schematic ground of modernity. Perhaps what Anastasia is driving at is something similar: peeling back the layers of ecology to visualize the machinery of interconnection thrumming away deep in its heart.

And yet, what to make of those sculptural elements that she affixes to her fields of abstraction? Those phantom orchids and serpentine arms? They’re modeled in architectural software and printed out of a glass-polymer composite. They lay rigid and artificial over the wimpled hides of her canvas, impeding our view of those ineffable, intangible fields; they are both a part of the picture plane and undoubtedly separate. See Hox, named for the genes that determine how embryos grow on the head-tail axis, with its articulated spines inching like centipedes across the corners of the frame, or the thorny musculature that grips the borders of HeLa, named for the immortal cell line of Henrietta Lacks, which can divide itself, miraculously, an unlimited number of times. These structures seem to have a different organizational logic than the swales of her canvas, one more firmly rooted in the shapes of biology, full of so many flowers and spines and leaflike vascularity.

Amidst all this talk about hidden symbolic substrates, one might view these ornaments as some sort of invasive species, creeping as they do out from behind the picture before venturing off of it and into open space, eager to find another surface to colonize. Their scientific naming and biomorphic formalism seem to stand in contrast to the unstructured undulation of the canvas below. And science, after all, can so often be exploitative, extractive - think of Henrietta Lacks, whose miraculous cell line was harvested from her dying body without her knowledge or consent, or of the unending proliferation of world-destroying toxins that have been brought forth through corporate research and development.

Anastasia’s polymer sculptures might seem at first to operate on a similar drive: they are consistently self-propagating, growing across the sense-making symbolic layer, obscuring the aether. But in Anastasia’s artistic worldview, such material-spiritual divides are not so easily prescribed. Her abstract fields and her plasticine creations often hew closely to one another in form: see how Cnida’s blade-like root structure follows the curves of the grassy plane below, or how Auxin’s tear-dropped leeches cling to the central bell shape along its fluted sides. This may be symbiosis rather than dominance or invasion. In the ordered creation of Hosts, the relationship between spirituality and science, between layers ineffable and physical, is contingent, continuous even - they are not antagonists but rather successive sheaves in the same grand design. And here might be some inherent meaning: that our own world might be similarly continuous, from cells and viruses and whirring high-rises downtown to the inscrutable geometry that orders them all.

Justin Kamp