Groupshow

Extraneous

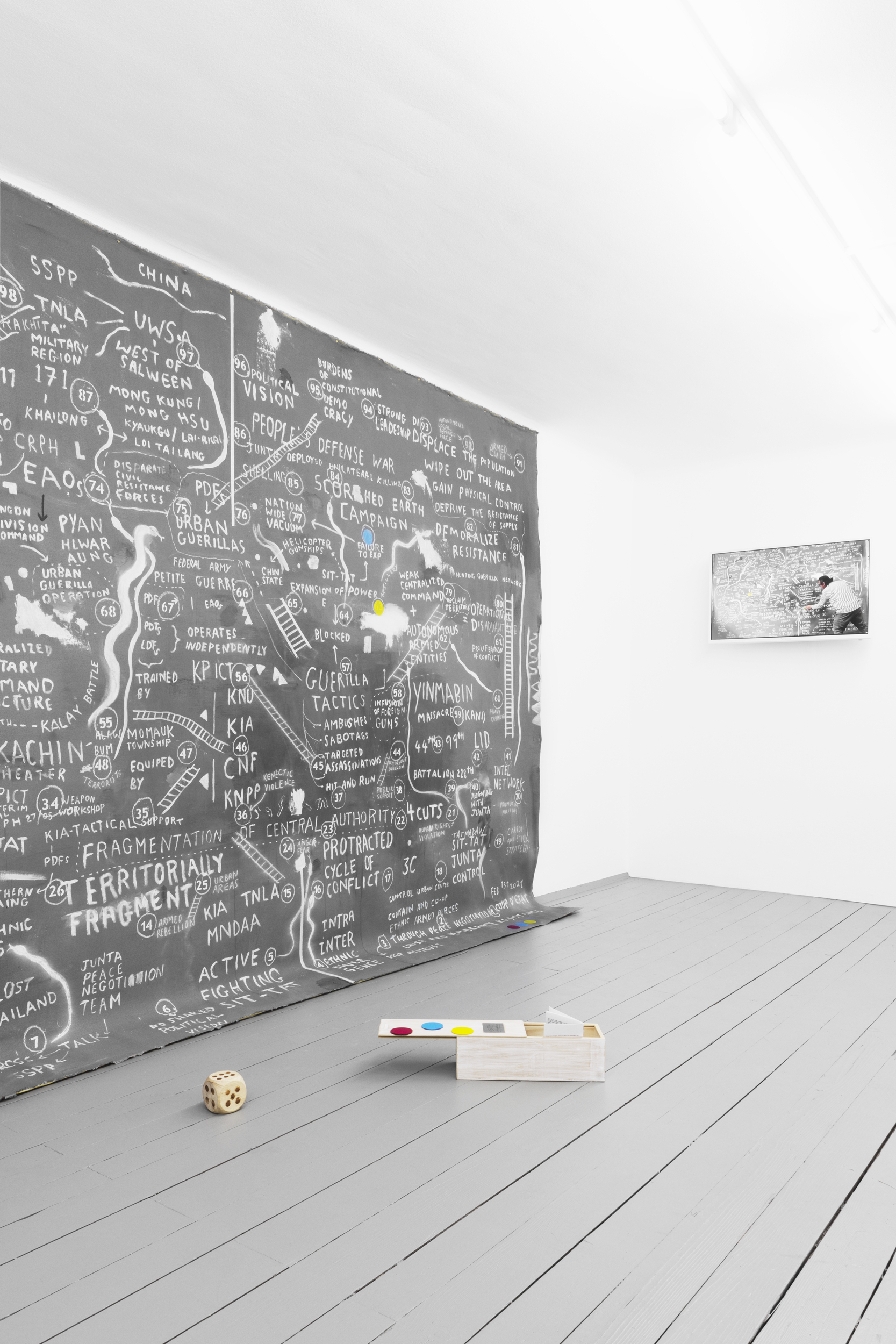

Extraneous, 2022. Installation view, EXILE

Advertisement

Extraneous, 2022. Installation view, EXILE

Extraneous, 2022. Installation view, EXILE

Extraneous, 2022. Installation view, EXILE

In arid soils, people put matkas at their doorsteps, on the street.

A lidded terracotta jar, and a tumbler to drink from

For the thirsty.

The extraneous domestic gesture of placing a pot of drinking water on the street outside for the stray passer-by creates a small space, the tiniest space of reprieve, a narrow opening for the not-quite encounter. This extraneous, extra act – puts a foot – in the doorstep, in the piazza, the courtyard, leaving open space for territories out of territory to emerge, or extra-territories.

The artisanal water pumps recycled from old washing machines in refugee-camp courtyards in the work of Margherita Moscardini, the fountain in the window- shattered piazza in the work of Nazar Strelyaev-Nazarko, and the matka at the doorstep are extraneous. They are sites of meeting, capable of encounter, capable of reimagining affiliation, the polis, citizenship, refuge. They fuse with the possibility of extraterritoriality exceeding national ideas of jurisdiction, sovereignty, constitutionally given identities and monumentality. Moscardini’s clay models of Arab courtyards, many unfired, are fragile copies of fountains refugee-designed, and community-built by Syrian refugees in Jordan. The real fountains and square courtyards are miniaturised into clay reproductions, one-tenth in scale, of the immaterial negative space of the courtyard. They are also models for future fountains to be built in full-scale on European soil. Legal documents need to add to existing national law, in order to render these zones of refuge, or vacuums in the law, black holes in national soil.

In The Fountains of Za’atari, the courtyards are semi-public squares, and their central fountains are theorised as akin to private monuments. Moscardini’s models have a gravitational weight when one holds them, they are foundation stones of another way to define citizenship, based not on territorial belonging, but its opposite, based on exile of belonging to a polis, emancipated from ideas of nationality and territorial belonging, and the political order, defended by military forces, that rules the planet. Her work rehearses the recovery of the nation from the nation- state. The nation does not need a territory. Whereas the commons, common resources and common lands are sanctioned by the sovereign state, Moscardini argues for the res communes omnium, the international commons, surpassing any idea of nation- state. The extraneous artistic act in Moscardini’s whole project is in how illegally concrete unsanctioned water pumps in the temporary cities of refugee camps, are converted into the drafting of illegalities into binding legal documents of international jurisdiction for the projected real-scale fountains.

Children’s watergames in the annotations by Strelyaev-Nazarko, shoot water at happy parents in bathing suits playing in the ruins of a statue, are many histories and times combined within the Plóshcha Svobódy (or Freedom Square) in his hometown Kharkiv. The Derzhprom building in the background—the first constructivist skyscraper of the Soviet Union; children playing with water around a missile that failed to explode; and the ruins of Lenin’s hulking statue—toppled and demolished in 2014—coexist in an imaginary Romantic landscape under exploding meteor showers. When the towering monument of Lenin was pulled down, first statue, later pedestal, Italian architects were commissioned to design a European public fountain.

How does playing a game, over and over again, rehearse resistance? An oily salesman pitches this to us in the Instruction Handbook of the Musée d’art Moderne Yawnghwe. Quoting Duchamp’s objet trouvé, a wine box contains a dice and circles to move across a canvas according to the roll of fate. The Video Demonstration begins with stylised Chaplin mannerisms, in a double role miming player and opponent, counting moves to himself. His striped t-shirt recalls the mime, the juggler, photographs of Picasso, or the antics of Dada.

Extraneous space is created each time the game is played, where potential acts of re- imagining and rehearsing possible futures open extra-territories of resistance. The game we are invited to play in the space, is based on a 2022 report on happenings since the coup in Myanmar that began on 1/2/21. The titles of the various squares lay bare the stratagems of resistance armies, civilian and people’s armies, climbing up ladders and sliding down snakes against the state military and state-funded militias. “… the chance to win, or die”, in an asymmetric war with loaded dice.

The installations by Milica Tomić and Sawangwongse Yawnghwe that run parallel on the upper level of EXILE, both stare into the making of genocide; in particular the Srebrenica massacre in 1995 during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s; and the world’s longest-running civil war in Myanmar in South-East Asia between state forces and persecuted ethnic armed rebel groups; among whom are the Rohingya, rendered stateless after the citizenship act in 1982.

Written constitutions and juridical contracts design identity. They impose identifiers onto populations which begin to be accepted as natural through the social contracts—the unwritten Instruction Handbook of the nation-state we were never invited to sign—whether so that each ethnic group is ensured representation and power within the state, or to isolate people as minorities, second citizens, or even stateless, they always codify people to self-identify according to neat labels. The legal scholar of contemporary South African law, monuments and post-apartheid museums, Stacy Douglas, theorises (in Curating Community: Museums, Constitutionalism, and the Taming of the Political, 2017) that art spaces and museums can create ground for exceeding the constitutionally-derived labels of identity, and nation-state narratives of history. She exhorts that ethnocultural identities be exceeded by counter-monumentality. This excess, opens up space for new forms of belonging, association and encounter. The Monument Group’s project addresses the act of identifying victims of genocide based on human remains from a mass grave in Srebrenica. “Are a femur, a tooth, a rib and part of the skull enough for you? What is the bare minimum you would identify as a body, would call a body?”, asks Damir Arsenijević (in Gendering the Bone: The Politics of Memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2011). Genocidal governments impose an identity, also to those which can no longer reclaim their own, an identity that facilitates the naturalisation (they are re-named “missing persons”) and the justification (often invoking ethnic minorities) of violence and the politics of terror.

What extraneous space is opened by the extraterritorial (Moscardini) or the unidentified (Tomić)? Can a fragment of recovered bone from mass graves—a failed forensic identifier, contain also an excess, open space for abstract, infinite possibilities of identification (Grupa Spomenik)? Could the infinite possibilities of identity, rejoice against identity politics, and constitutional, nationally-sanctioned minorities or borders?

Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani