Agnes Scherer

A Thousand Times Yes

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Advertisement

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times good night, 2022, plaster gauze, plaster, canvas, acrylic paint, ribbons, paper, variable dimensions, unique

Agnes Scherer, A thousand times yes, 2020, exhibition, Sans titre, Paris

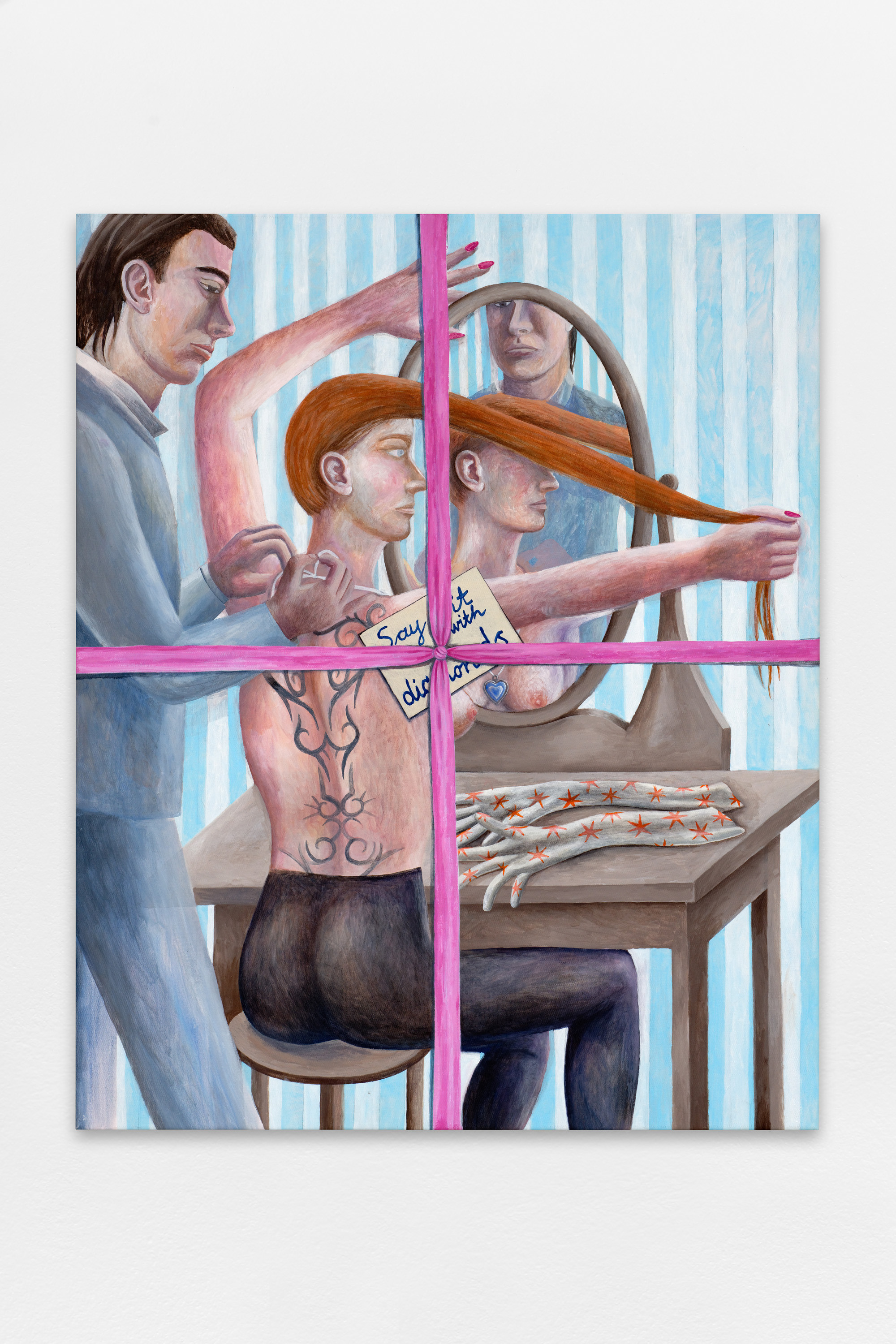

Agnes Scherer, Say it with diamonds, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 100.5 x 82 cm, unique

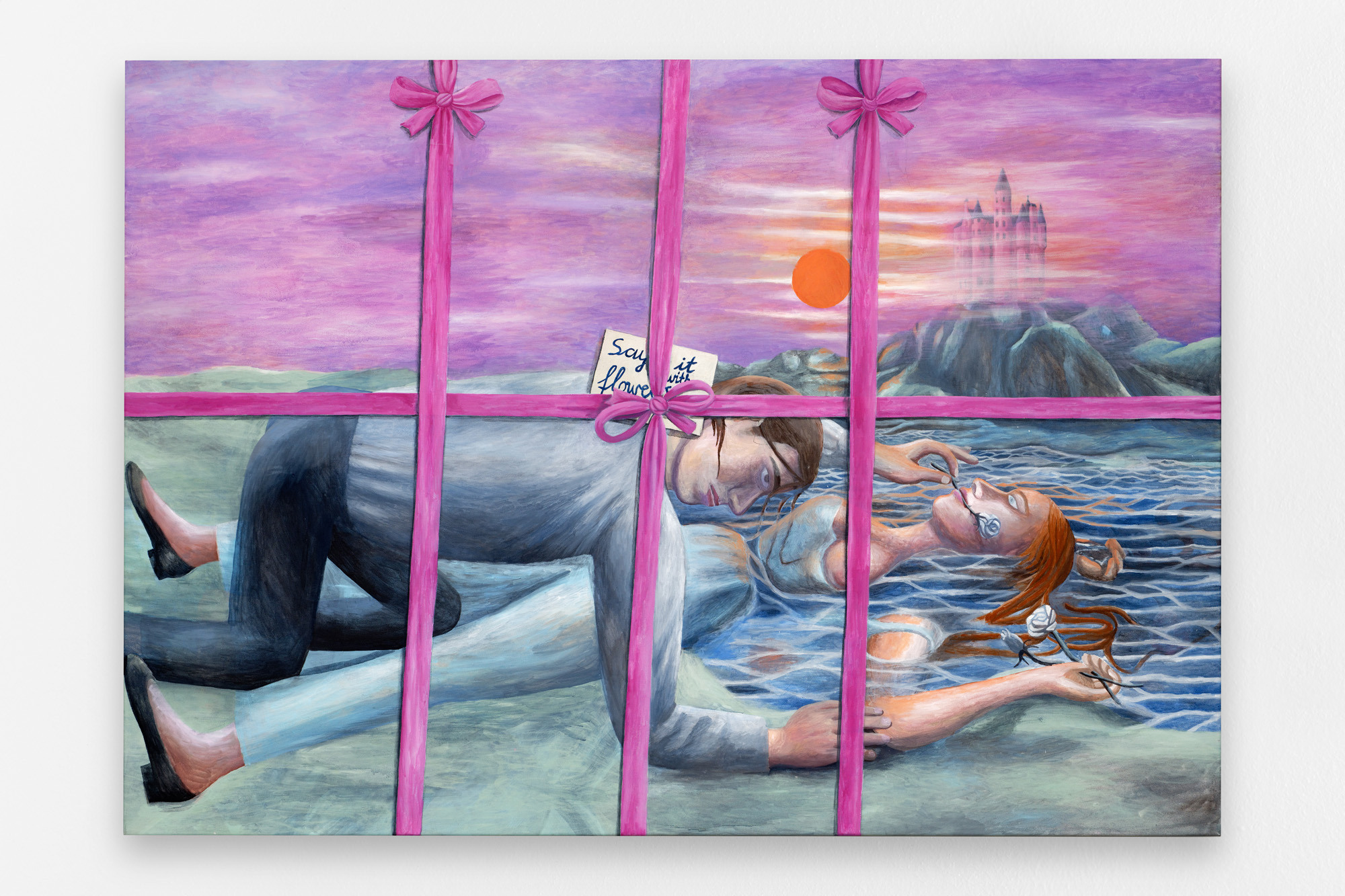

Agnes Scherer, Say it with flowers, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 99 x 140 cm, unique

Agnes Scherer, So much more than words can say, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 68.5 cm, unique

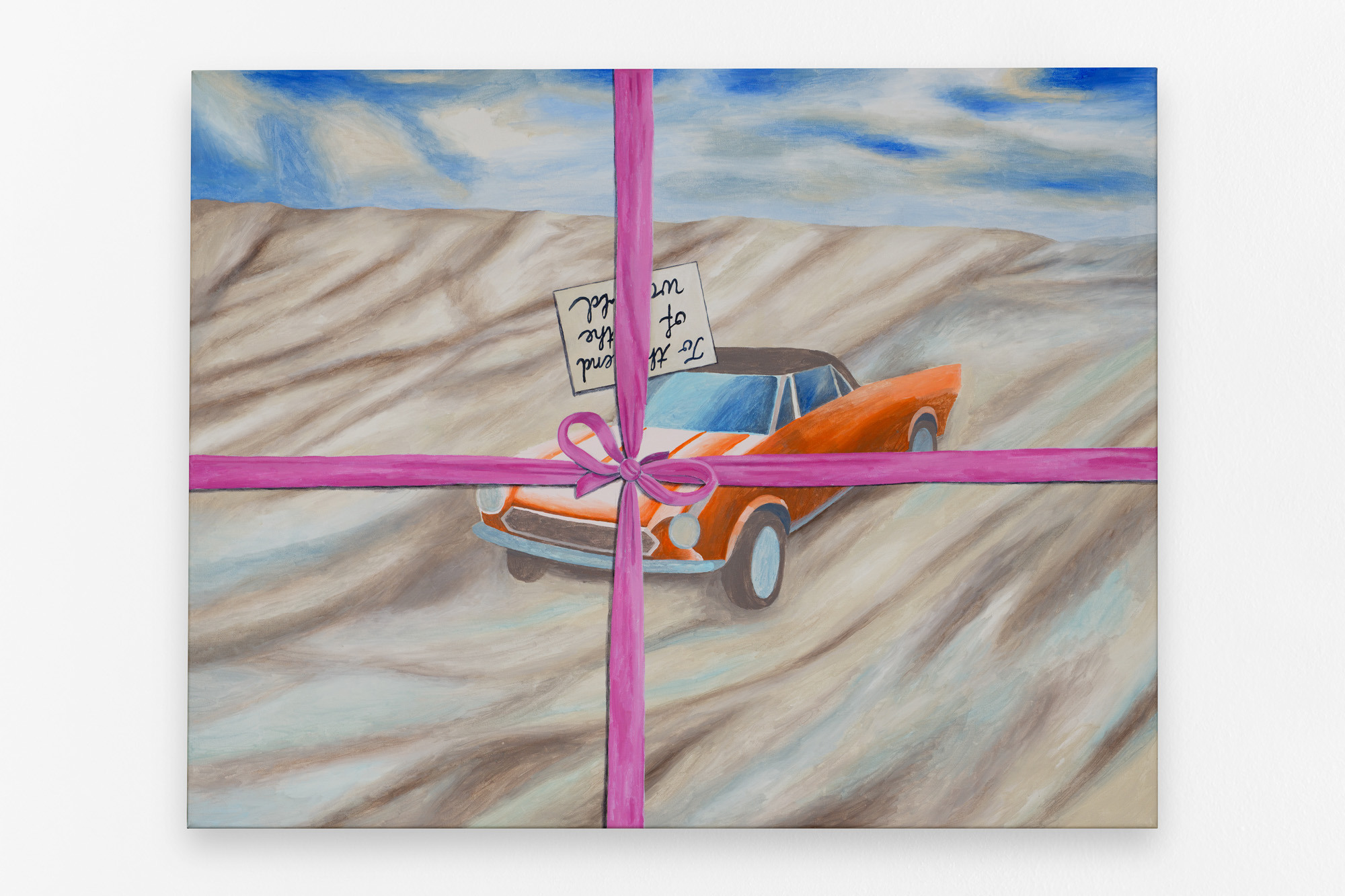

Agnes Scherer, To the end of the world, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 78 x 100 cm, unique

Currently on view at gallery sans titre, Agnes Scherer’s solo exhibition A thousand times yes consists of an immersive installation including a series of new paintings and sculptures portraying a fictional wedding.

Humorously referring to the current obsession some middle-class, Instagram-savvy, Western women seem to have with their wedding day, Scherer selected and interpreted some symbols and gestures offering a comment on the excesses of western capitalist societies, while reflecting on the heteronormative organisation of power.

The exhibition borrows its title from Jane Austen’s 1813 Pride and Prejudice, who portrayed the trade of marriage in Pre-Victorian times with an accuracy whose subtle cynicism provided inspiration to the current exhibition. For Austen, the organisation of marriage was devised according to the mutual (and financial) interests of two families willing to grow their economic

power through alliances.

Such straight-forwardness got messy when mutual love entered the equation. The Enlightenment’s promotion of individualist values included the right to self-determination through romantic love. Outdoing any previous approach, today’s capitalist marriage accomplishes the remarkable feat of combing economic and romantic values as its core raison d’être. Only then can a marriage be considered successful. Crucially, with the rising role of Instagram and other social media as the measuring tools of success, wedding ceremonies seem to illustrate the obscene demise of capitalist’s current regime of ideas.

Scherer’s bride could well be the result, or rather the victim, of centuries worth of political and social aspirations, ranging from pre-modern economic straightforwardness, to Enlightenment’s individualist revolution, feminist’s liberation movements and more recently the schizophrenic emotional vagrancy of Netflix’s Love is Blind’s marriage candidates. The ritual of marriage, just like art, seems to be ready to absorb the political ebb and flow of any given generation.

Although the artist emphasised that the exact socio-cultural profile of her bride and groom wasn’t crucial to fully grasp, she nevertheless wanted them to bear a range of average features which would allow the viewer to picture what many may define as the “norm”. Not entirely auto-biographical, Scherer’s exhibition however speaks about issues that most women with similar socio-economical background are dealing with. That is, a life whose success is measured by white heteronormative imperative, such as the ability to marry, bear children, and have a successful professional career. Scherer thus opens a space for self-inquiry and looks at the damages caused by Western patriarchal thinking, which is defined, mainly by a heteronormative, binary, and essentialist vision of the world. She uses an hyperbolic approach, by means of an excessive and archetypal version of a wedding ceremony, to reveal the socio-political attachments that are naturally embedded in it.

Even though a Thousand times yes mainly speculates around the vision of a young woman’s idealised wedding, crucially, the role of the man is subtly yet sensibly challenged. If Scherer’s groom first appears as Prince Charming, some details may suggest otherwise. In fact, we see in A thousand times good night an embrace betraying a lopsided relationship. It’s hard to conclude whether the bride is in fact trying to escape the embrace or if she simply is resigning to it. Regardless, with his head geared at the bride’s throat, the groom’s posture recalls a vampire’s kiss, symbolically attesting women’s social subordination to men. Meanwhile, the bride keeps her balance while leaning on a painting that represents a car wrapped like a present, suggesting that she may trade her integrity in exchange of luxury goods.

During what should be the ceremony’s climax, the subjectivity of Scherer’s bride is de facto taken away by someone ready to symbolically (and too often literally) eviscerate her. Simone de Beauvoir was on point, when, during a TV interview from 1959, she explained that marriage was “obscene” for the loss of subjectivity and sovereignty it inevitably caused to those surrendering to it. Similarly, Scherer seems to suggest that a wedding is nothing less than the celebration of women’s disappearance.

Reflecting on this, her research led her to conclude that femicide has been romanticised and celebrated in pop culture for decades, while often presented as the ultimate act of masculinity. One reference that informed Scherer’s installation, and gave its colour to the bride’s mane, is Kylie Minogue & Nick Cave’s 1995 music video “Where the Wild Roses Grow”. A huge success of the mid 1990s, the video is a ballad telling a “love” story in which the lover’s passion is so strong that he ends up killing his bride.

Similarly, the Highlander romance literary genre greatly contributed to normalise romantic violence, with characters whose manhood is often only proved at the cost of violence and aggression towards their (female) lovers. Here, the brutality of the white cis-male hero is justified as a “natural” feature and what makes him sexy. More recently, the planetary success of E. L. James’ erotic novel 50 Shades of Grey further reinforced the idea that women are thriving in romantic relationships involving physical and psychological abuse.

More than an upfront criticism of the patriarchal, capitalist organisation of gender roles, A thousand times yes is about the banality of violence. The dramatic effect of Scherer’s installation precisely lies in its ability to trigger a level of empathy. With her use of camp and extravagant aesthetics Scherer willingly escapes any clear positioning or judgement, rather she suggests that she, like most of the viewers, may be complicit.

Elise Lammer