Myles Starr

"Happy""35th"

Exhibition view, VIN VIN, Myles Starr, "Happy" "35th"

Advertisement

Exhibition view, VIN VIN, Myles Starr, "Happy" "35th"

Exhibition view, VIN VIN, Myles Starr, "Happy" "35th"

Exhibition view, VIN VIN, Myles Starr, "Happy" "35th"

Exhibition view, VIN VIN, Myles Starr, "Happy" "35th"

Myles Starr, The Bicycle Theif, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, The Bicycle Theif, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, The Bicycle Theif, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, The Longest Day, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, The Longest Day, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, The Longest Day, 2022, Oil on canvas, mylar, resin, steel track and hardware, 101.6 x 152.4 cm

Myles Starr, Mean Girls, 2022, Oil on canvas, cast resin, hardware, 51 x 51 cm

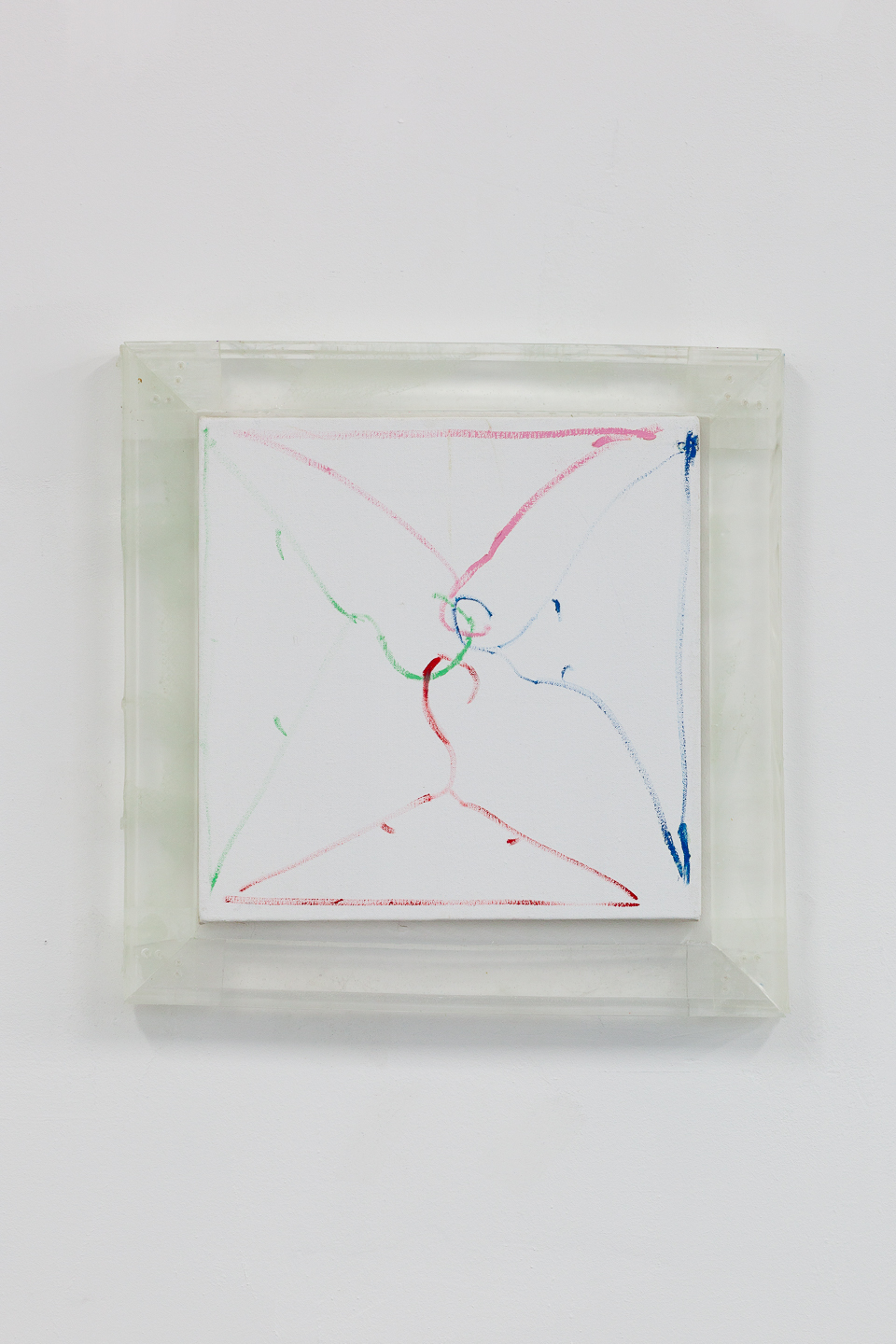

Myles Starr, Down by Law, 2022, Oil on canvas, cast resin, hardware, 51 x 51 cm

Myles Starr, A Single Man, 2022, Oil on canvas, cast resin, hardware, 51 x 51 cm

Myles Starr, A Single Man, 2022, Oil on canvas, cast resin, hardware, 51 x 51 cm, Detail

“Happy” “35th” commemorates Myles Starr’s thirty-fifth year. The work presented in the exhibition is reflectively sentimental and intimate, dredging concrete details from the artist's past but leaving plenty of room for interpretation in his canvas’s extensive whitespace.

Native to New York City and returning after a ten-year expatriation, Starr grappled with the difficulty of finding affordable studio space. Having discovered a loophole in City law that allows wheeled objects to be chained to fences without the threat of removal, he set up a makeshift workstation where he produced resin sculptures, including the clear cast stretcher bars that are part of the three smaller works in the show.

While Starr is explicit that he does not want to make art about New York City, memory and material reality directly influence his subject matter. US-American urban environments contain grit; this quality of perseverance exists in his work alongside notable introspection. The sweaters painted are relics of childhood. The titles of the pieces are the names of family members' favorite movies. The paintings suggest a haunting.

Psychoanalysis may be the most standardized approach to unearthing the unconscious, but creativity can be similarly utilized to uncover unseen forces in the world. Artmaking is a process of transmutation where the work alters the artist as much as the raw material is altered by the artist. Making the immaterial material is a complex task, one that engages with the self to address concepts that may not be fully actualized or seeable.

Arguably, all artists mine themselves for subject matter, revealing in their work intimate details. But Starr renders paintings that have as much merit in themselves as in their backstories. This is not coincidental as he staunchly maintains that art should not require written elucidation to be understood. “Art,” Starr states, “needs its ambiguity, its uselessness, its beauty, its lies.” This noted, his process does utilize the dimensionality in his life: the meaning of memory, of possession. Starr’s work argues that objects can testify to dramatic events by giving embodied shape to memory. Efforts to save and protect objects prove their power.

Even without explicit knowledge of “35th”’s garments, they contain a familial undertone. The sweaters are childlike and old simultaneously, and their colors are retrograde. A closet of gravity-defying hangers feels appropriate. The empty hangers are suggestive of loss and potential return. Mylar and resin on steel tracks provide a cover for two of the pieces. When the screen is drawn the viewer sees a distorted version of themselves in a funhouse mirror.

“Happy” “35” does not need to be demystified, but there is a clear engagement with self-analysis throughout the exhibition. Literal and figurative veiling exist in each piece. Detailed knowledge of the conditions of the work is unnecessary to appreciate the paintings and this allows a type of intended transference by the viewer onto the exhibition. While far from didactic, Starr offers a kind of lesson in looking: a way to appreciate aesthetics by its own caliber while simultaneously giving visual palimpsest to his unconscious.

Katie Ebitt