Angélique Aubrit & Ludovic Beillard

Je veux que tu meures

Project Info

- 💙 Galerie Valeria Cetraro

- 🖤 Angélique Aubrit & Ludovic Beillard

- 💜 Oriane Durand

- 💛 Angélique Aubrit & Ludovic Beillard

Share on

Advertisement

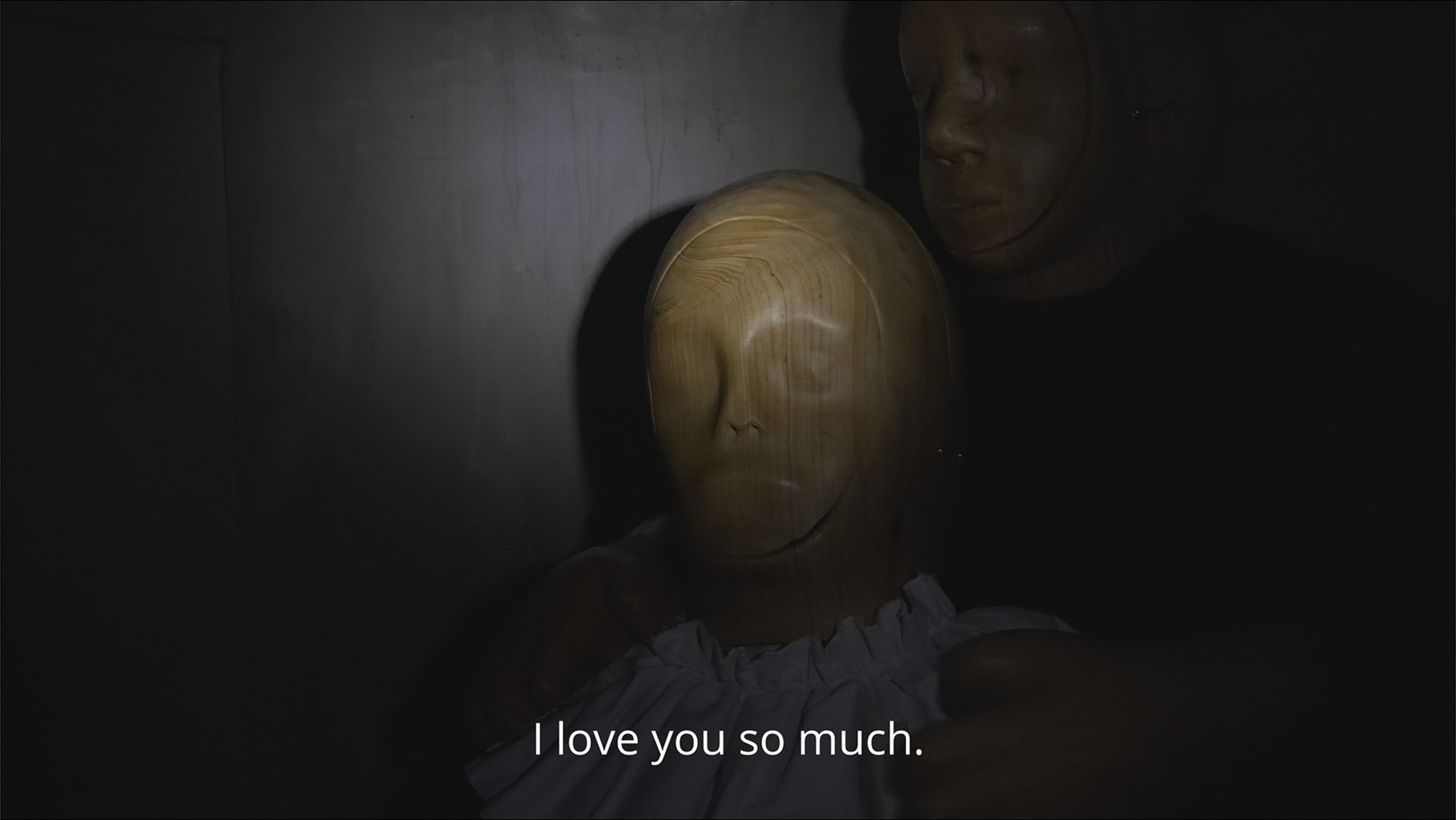

It can happen to wish that the people closest to you, or even those you love the most, die. In any case, it happened to me. I even recommend it, it feels good: to think of a death that relieves, a death that frees you from judgement, from suffocation or from unconditional love. Or simply wanting to interrupt the heaviness of the one who talks too much, the one who no longer perceives the limits, who encroaches and spreads out to the point of denying the other. Sometimes it becomes physical, when the body can no longer bear the presence of the other. Je veux que tu meures (‘I want you to die’) expresses, in my opinion, the wish for an instantaneous disappearance, more than a real death; it would be like the obliteration of a body floating in space, gradually disappearing into the blackness of the universe, into nothingness. Without knowing where the body goes, without knowing if it really dies, be that as it may, it disappears once and for all from sight and from any possible link. In other words, what do we actually do when the other person stifles us or when we simply can not stand the one in front of us? Are we going to see an ancient play, Andromache, Antigone, in order to experience a catharsis? In my personal opinion, I would choose Penthelesia (1808), the Greek myth rewritten by Heinrich von Kleist. It tells the story of the queen of the Amazons who, during the Trojan War, ‘unwittingly’ kills Achilles on the battlefield, with whom she simultaneously falls in love. As for them, Angélique Aubrit and Ludovic Beillard have written a script that stages the meeting of five characters in a tightly enclosed space where a zany and disturbing tension reigns. The resulting film, like the exhibition set-up, places these characters in an environment that borrows the architectural characteristics of a spaceship. Here on earth, the gallery space, itself small, has been reduced, recalling the confined and claustrophobic atmosphere of these interstellar vehicles. The costumes-sculptures of Élena, Mauris, Heather, Niklas and Pete are presented next to each other, leaning against the wall like cosmonauts’ clothes in a decompression chamber. The film, on the other hand, shows the characters in a circular cabin with six doors, the walls of which ooze humidity. The characters pass each other, talk to each other, bump into each other, wait for each other and move around. The situation between them seems unstable, sometimes heavy and threatening - are they going to kill each other? - sometimes ‘relaxed’ between two puffs of a cigarette. The heterogeneity of their clothes suggests that they come from different times and backgrounds. Perhaps Élena, Niklas, Heather, Mauris and Pete don’t know each other, perhaps they have found themselves there, as in Sartre’s No Exit (Huit clos, 1947), where three strangers meet in hell; a hell where there are no executioners or instruments of physical torture but only each other and their implacable judgment. Or perhaps we attend a scene like in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) where the crew members, under high tension, gather around Ripley in order to review the threat on board the ship. The singular physicality of these characters, with oversized wooden forearms and heads that limit their movements, place them at the crossroads of these two stories. While the faces on the wooden helmets have distinct features, their eyes remain unnoticed, as if they were closed. Without ocular presences, these faces seem like death masks. The fragility of the human body shown by the wooden armour, the isolation of the characters, the style of the film and the costumes, each element, whether aesthetic or narrative, contributes to the production of an intermediate state, a tragi-comic airlock.

Oriane Durand